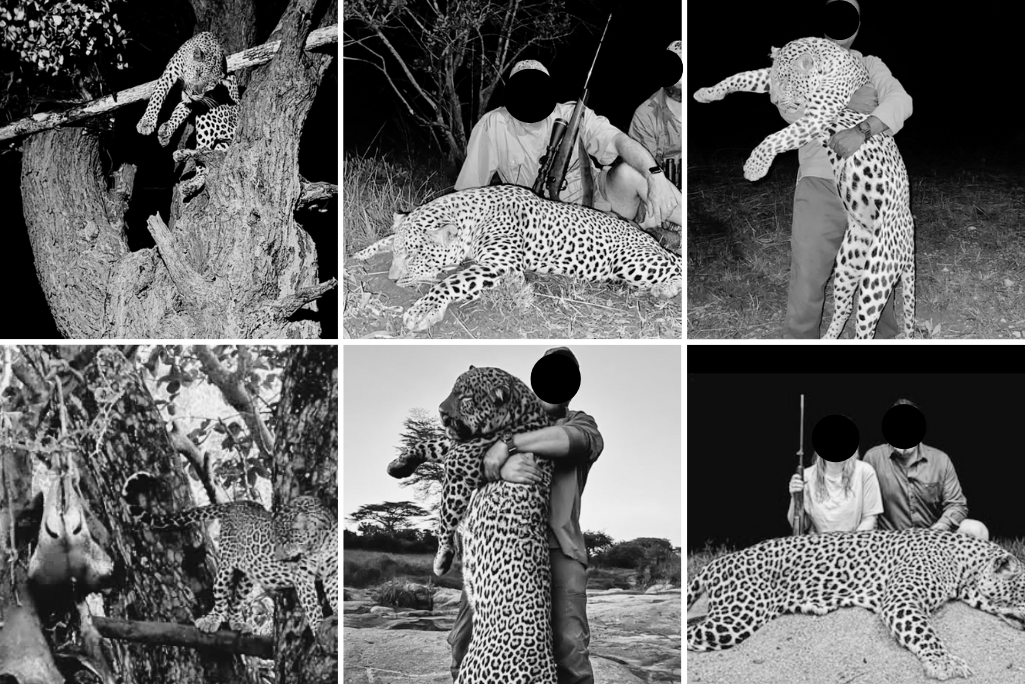

Many studies have identified trophy hunting as a key driver of the decline in the number of leopards. (Photo: Africa Hunting website)

By Don Pinnock Following 09 Jun 2025

A new report documents unabated hunting despite leopard numbers plummeting across Africa.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

At night, in the African bush, a zebra carcass dangles from a tree, rigged as bait. Nearby, a hunter waits in a hide, rifle trained, night-vision goggles focused. When the leopard arrives — silent, cautious, regal — it climbs for its meal. A crack splits the night. The cat falls, dead before it hits the ground.

Later, its skull will be dried, measured and entered into a record book. The hunter will go home triumphant, the leopard’s skin later draped across his study wall. Meanwhile, in the wild, the species edges closer to extinction.

This scenario is from a new report commissioned by the Wildlife & Conservation Foundation, The Leopard Hunters, which uncovers the scale and players behind the global leopard trophy hunting industry. It points to a disturbing nexus of wealth, status and political influence driving the killing of one of Africa’s most iconic predators.

According to the report, more than 700 leopard trophies were exported from Africa in 2023, despite the species being listed under Appendix I of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (Cites) — a designation reserved for species at risk of extinction, where trade is meant to be highly restricted. Of those trophies, half went to the US, making American hunters the largest importers by far. Most of the rest were shot by hunters from Europe.

More than 700 leopard trophies were exported from Africa in 2023. (Photo: Africa Hunting website)

Leading the pack was Steve Chancellor, a US billionaire and close political ally of President Donald Trump. Chancellor, the world record holder for the largest leopard ever shot, is reported to have killed around 500 animals for trophies, including 50 lions and five cougars, some reportedly shot with a handgun. His California home — where he once hosted Trump fundraisers — is described as a private museum of taxidermy.

“Chancellor was part of a White House advisory committee set up to weaken protections for threatened species,” notes the report, highlighting his influence on policies that made it easier to import trophies of endangered animals into the US.

He’s far from alone. The report names a Who’s Who of high-profile hunters whose names fill the pages of the Safari Club International (SCI) Record Book – a status symbol in the world of big-game hunting. Spanish hunter Tony Sanchez-Arino, a friend of former King Juan Carlos, has killed 167 leopards. Zimbabwean hunter Ron Thomson boasts of killing 30. The late Donald Holt, a renowned taxidermist, once held the world record for the third-largest leopard. There are currently a total of 2,071 leopards in the SCI Record Book.

Big money

This is not just about individual egos. The report describes an industry propped up by safari companies, international hunting fairs and online marketplaces like BookYourHunt.com, where leopard hunts sell for up to $156,000. Some packages bundle leopard hunts with lions, elephants, crocodiles — even cheetahs.

“The trophies include bodies, bones, skins, skulls and leather products,” states the report. “Trophies are measured, scored and logged in record books. The bigger the animal, the greater the prestige.”

Yet beneath the glamour lies a brutal reality. Accounts collected in the report describe questionable hunting methods: baiting leopards with live or freshly killed animals; wounding cats and chasing them for days; setting fires to flush out hiding animals.

“Dragging a squealing, gutted duiker across the ground to a tree where it was wired up (still alive) to attract a leopard to shoot after dark … diesel used to pour into warthog holes where a wounded leopard had run and then set on fire,” one account reads. In one case, “over 200 rounds of gunfire shot into a palm island where they thought a male lion was holed up, but ended up shooting his pride and eight cubs. Later, setting the palm alight to ‘smoke the sucker out’.”

The spoils of a hunt. (Photo: Ricky Clark website)

Numbers plummeting

The ethical concerns are compounded by the conservation crisis. Population estimates are uncertain (leopards are nocturnal, secretive and hard to count), but it’s widely believed that numbers have fallen from around 700,000 in the 1960s to roughly 50,000 today — a decline of more than 90%.

While habitat loss and conflict with humans are factors, many studies have identified trophy hunting as a key driver of the decline. Leopards were classed as Least Concern on the IUCN Red List as recently as 2008. They have since jumped two levels to Vulnerable. Despite this, Botswana has just submitted to Cites a plan to reinstate leopard hunting.

Ironically, hunters often claim they are conservationists. Safari Club International (SCI) and affiliated groups argue that trophy fees fund wildlife management and anti-poaching efforts. But conservation scientists are sceptical.

“The evidence shows that trophy hunting is having negative impacts across sub-Saharan Africa,” the US Congress concluded in a survey cited in the report. “Unsustainably high rates of trophy hunting have caused population declines in African lions and possibly African leopards.”

Zambia banned leopard trophy hunting in 2013. In South Africa, the Department of the Environment imposed moratoriums on hunting following legal challenges from NGOs. It has not published the finalised leopard hunting quotas for 2025.

Even when governments respond, the industry fights back. The report describes how Conservation Force, a legal group founded by former SCI president John J Jackson III, sues governments to reverse trophy import bans. In New Jersey, for instance, Conservation Force won a court case overturning a law prohibiting the import of trophies of the Big Five.

Meanwhile, the biological consequences go beyond mere numbers. By selectively targeting the largest, strongest animals, trophy hunting triggers “artificial selection” that weakens the gene pool, says the report. Removing dominant males reduces genetic fitness and disrupts social structures, undermining the species’ ability to adapt to environmental changes like climate shifts.

And yet the race for trophies continues. Awards like SCI’s African Big Five, Cats of the World, Predators of the World and Dangerous Game incentivise hunters to kill specific species. To qualify for the Hunting Achievement Award (Diamond), a hunter must kill at least 125 animals from different species. Leopards are a critical rung on this ladder.

SCI publishes guides which tell trophy hunters where to go to shoot “huge leopards and excellent maned lions”. Leopards can also be shot with handguns, crossbows, bows and arrows and with old-fashioned muzzleloaders to win the Multiple Methods Award.

“It’s not about meat or survival,” argue wildlife campaigners in the report. “It’s about prestige, status and the thrill of the kill.”

Other ways

But alternatives exist. The report closes with the voice of Boniface Mpario, a Maasai elder and veteran wildlife guide in Kenya, who recalls building trust with a wild leopard he named Mrembo — Swahili for Beautiful.

“Each year, photographers came back to see her and her cubs,” he says. “One leopard brought so many visitors, so much income for the community. Not from hunting, but from watching.”

A leopard shot with a camera, rather than a rifle. (Photo: Don Pinnock)

Mrembo has since raised multiple litters. Her daughters now have cubs of their own, continuing a family line that draws tourists — and tourist dollars — to the Maasai Mara. Unlike the bloodied records of the hunters, Mrembo’s legacy is one of life.

The Wildlife & Conservation Foundation, which commissioned the report, is calling for an immediate global moratorium on leopard trophy hunting.

“If elephants were native to the United States, and endangered or threatened, they would not be hunted,” said Dan Ashe, former director of the US Fish & Wildlife Service. “And neither would lions, rhinos, or leopards.”

For now, the leopard remains in the crosshairs — its future caught between the crack of a rifle and the click of a camera. DM