Posted on November 1, 2022 by teamAG in the DECODING SCIENCE post series.

Africa’s disappearing lions have been the subject of animated discussion for years, but just how dire is the situation?

Scientists now believe they have the answer: in five decades, the continent’s lion populations have declined by 75%. This according to research recently published by the University of Oxford’s Wildlife Conservation Research Unit (WildCRU).

The authors set out to establish a baseline lion population estimate and examine historic landscape connectivity for 1970 as a comparison point to assess the conservation of the species. They explain that conservation is subject to what has been termed a “shifting baseline syndrome”. In other words, current conservation efforts are often centred around present-day geographical ranges and population estimates. However, underestimating historical declines or trends could, in turn, underestimate extinction risk.

Disappearing habitats, dwindling lions

Habitat loss and fragmentation due to human population growth and agricultural expansion are among the most significant threats facing most terrestrial vertebrate families. Species surviving in fragmented and poorly connected habitats are more vulnerable to loss of genetic diversity, inbreeding depression, disease and stochastic events (such as drought). Lions are considered an umbrella species, meaning that conservation efforts aimed at their protection indirectly confer protection on other sympatric (co-occurring) species. They are also a charismatic representative of the range collapse experienced by many of Africa’s large mammals. Once widespread across Africa, previous research indicates that lions have experienced an 85% reduction in range since the early 16th century.

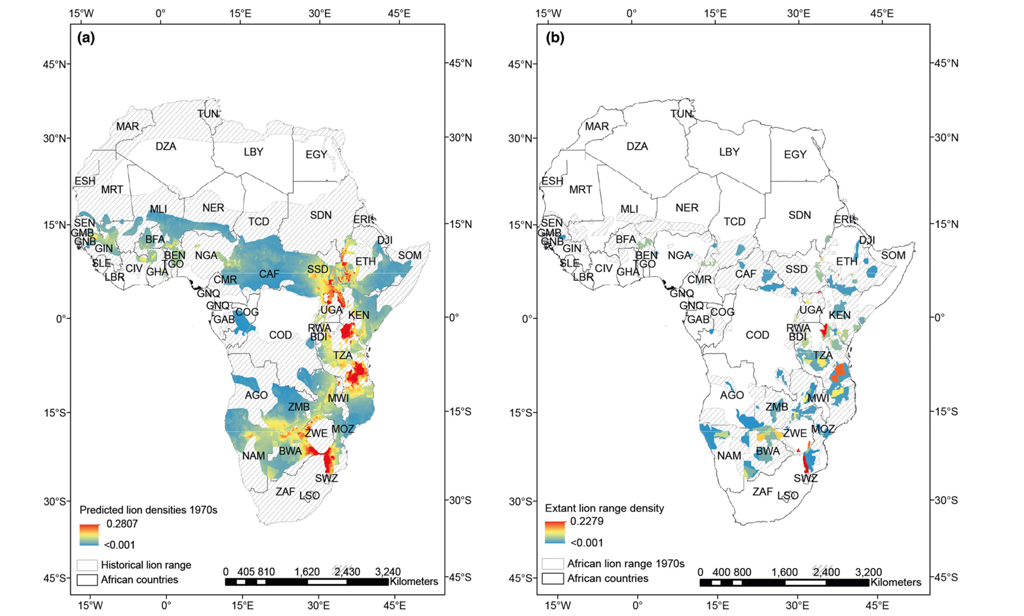

Reconstructing historical populations and distributions is a challenge facing many large-mammal scientists, as records are often scant and generalised. The authors selected the period around 1970 for their baseline for several reasons, including the existence of credible and detailed sources of information on lion ranges and populations. Furthermore, human population and development have burgeoned during the 50-year-period between 1970 and the present day, with the sub-Saharan human population doubling between 1975 and 2001. Using available information to construct a population density map of lion distribution, they derived an estimated population of 92,054 lions across the continent in 1970. At last count in 2016, the total surviving lion population was estimated at around 23,000 individuals (though experts believe it may now be under 20,000). This equates to a decline of 70,000 individuals – approximately 1,400 lions per year over five decades.

Figure 1: ”African lion density (N/km2) across (a) recent historical (c1970) lion distribution with population density derived from a generalised additive model; and (b) extant range showing lion population densities. Source: IUCN-SSC, 2018) (© Loveridge et al. [2022])

Disconnected lions

The researchers also examined lion subpopulations by area. Those in the Congo Basin have suffered most severely, and this subpopulation has been all but extirpated. From an estimated 1,600 lions in 1970, around 211 individuals remain – a decline of 93%. Similarly, the West and Central African subpopulations have declined by 87% (from 1,600 to fewer than 200). (The plight of the West African lion was recognised on the IUCN Red List in 2015 when they were listed as Critically Endangered.) Southern and East African subpopulations have fared slightly better but still declined by 73% and 65%, respectively. Southern populations declined from 36,000 to around 9,800, and East African from 31,000 to approximately 11,000.

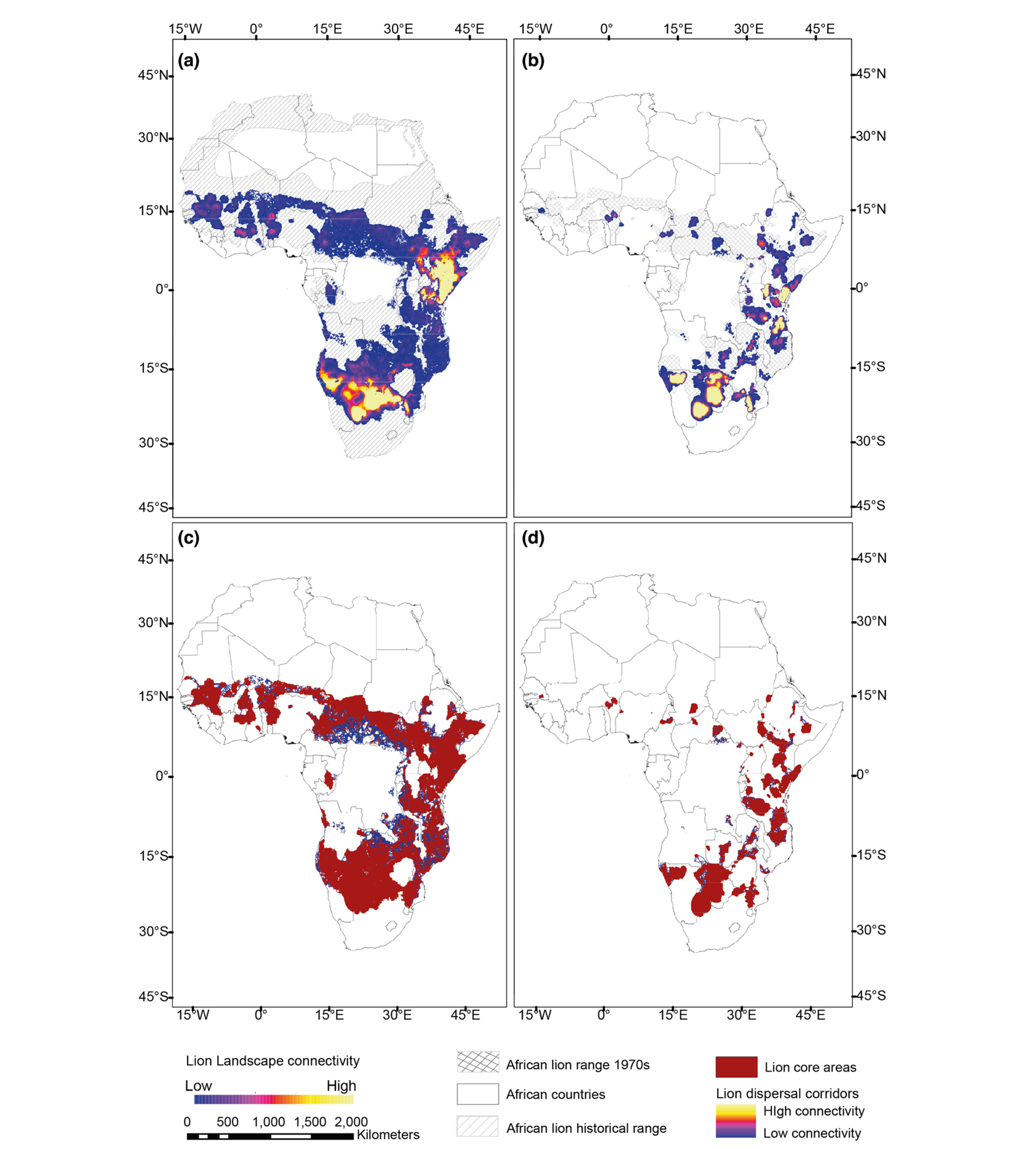

Remaining lion habitats are important but understanding the landscape connectivity between these is a vital aspect of lion conservation. The researchers analysed the landscapes within lion range in terms of resistance to animal movement, accounting for various environmental and anthropogenic variables (such as rivers, towns, farms and roads). This information was used to calculate the relative probability of animal movement to compare connectivity in 1970 to the present day.

In 1970, much of the existing lion habitat was well connected, apart from already fragmented habitats in the West and Central regions. For the most part, lion range was contiguous, with the potential for a high degree of dispersal movement across the landscape. Today, lions occupy just 13% of their maximum historical range (66% of the 1970 range), with the most severe range loss having occurred in the Congo Basin and the West and Central region. These regions have experienced a “catastrophic collapse in range and habitat connectivity in the last 50 years” – with fewer, smaller, and more widely isolated patches of core and non-core lion habitat. Loss of connectivity was less severe in southern and Eastern African regions but significant – around 50% of previously connected habitat was lost in the intervening five decades. The remaining core areas of habitat are centred around larger protected areas.

Figure 3: “Maps showing landscape connectivity for c1970 and current time periods. Top panel: Landscape connectivity resistant kernels in (a) c1970 and (b) the current period. Bottom panel: least-cost paths in (c) c1970 and (d) the current period. The shaded area represents historical range extent (right-hand maps) and recent historical extent (left-hand maps).” (© Loveridge et al. [2022])

The future of lion conservation

What implications does such research have for the future of lion conservation, given that human population expansion is inevitable? The authors emphasise that even if core protected areas are secure, a lack of connectivity will result in a decline in the genetic diversity of remaining lion populations. The protection of existing wildlife corridors is critical. They also suggest that intensive meta-population (as practised in smaller wildlife areas in South Africa) may be appropriate for irretrievably isolated habitats, such as those in West and Central Africa.

Though the damage done to the lions of Africa may never be fully recoverable, the researchers suggest that it is not too late to secure wildlife corridors “through integrated land use planning exercises, implementation of human-wildlife conflict mitigation strategies and enhancement of sustainable, wildlife-based livelihoods”.

“Habitat conversion and burgeoning human populations are fragmenting natural habitat across Africa,” says lead author Professor Andrew Loveridge. “Our work on African lions shows that this process of fragmentation and population decline has accelerated over the last 50 years and provides a baseline against which to measure population recovery or decline. Our future conservation efforts need to halt habitat loss and work to preserve the remaining habitat corridors linking core populations.”

References and further reading:

Loveridge A.J., Sousa L.L., Cushman S., Kaszta Ż., Macdonald D.W. (2022) “Where Have All the Lions Gone? Establishing Realistic Baselines to Assess Decline and Recovery of African Lions,” Diversity and Distributions

For more on how scientists used ancient ivory to analyse elephant population loss, read this: Of ivory, elephants, shipwrecks and slaughter

On the loss of lion genetic diversity as a consequence of population declines: Lion populations show significant loss of genetic diversity, say researchers

For a detailed explanation of the challenges involved in estimating lion populations: Counting lions: new study shows the importance of good counts for lion conservation

To support the conservation of lions in Africa, view more about the following projects:

– Desert Lion Conservation Trust

– Lion Landscapes

– Wild Entrust

– Mara Predator Conservation Programme