Could unmanned aerial vehicles make the difference in wildlife surveillance and protection, asks Russell Hughes.

Drone technology has already made a splash in the front pages, usually for its destructive power. Drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), are either controlled from ‘pilots’ on the ground, or follow pre-programmed flight missions. The military has been using UAVs to drop bombs on the enemy for years – but the technology can also be a protector, and a force for good.

In the field of wildlife conservation, it has the potential to be the next breakthrough in the fight to protect and help those who cannot help themselves. From the windswept beauty of the Northumberland coast to the sunbaked plains of Africa, drones are making a positive impact.

Coquet Island in Northumberland

Coquet Island in NorthumberlandNestled just over a mile off the coast of Northumberland is Coquet Island, which is a RSPB (Royal Society for the Protection of Birds) reserve. Dr Paul Morrison, site manager on the island, thinks that drone technology will prove to be extremely useful.

“There is huge potential for helping with monitoring of the nesting bird species on Coquet,” he says.

“In particular it would be very useful to help find large gull chicks that hide in the dense vegetation on the island, using an infra red camera. It would be interesting to see if a small loudspeaker could be attached to use as a scaring method for playing alarm calls to frighten large gulls from the island in spring and autumn,” Dr Morrison concluded.

The rhinos at Kruger National Park need urgent protection

The rhinos at Kruger National Park need urgent protectionHowever, it is the drone’s potential to protect that has got conservationists most excited. Around 8,000 miles away on the plains of the Kruger National Park in South Africa, there is a much bigger problem at hand – poaching. The grim statistics show that 747 rhinos have been killed in 2014 alone, according to the South African Department of Environmental Affairs.

But unless technology is designed to lower the price of hardware and improve the performance of such drones, their use will be beyond the budget of most parks.

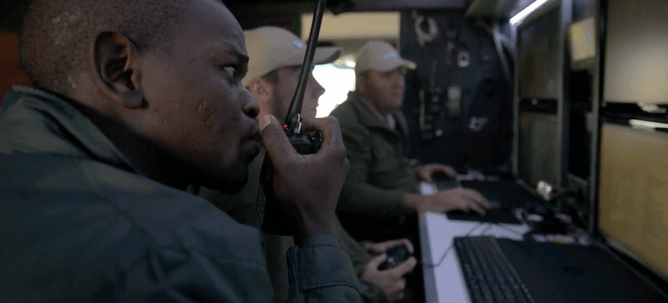

That’s where the Wildlife Conservation UAV Challenge comes in. It’s a competition that was founded to ‘foster innovation and invention in the design, fabrication, and utilisation of unmanned aircraft to assist with counter poaching and illicit wildlife trafficking.’ Its aim is to design low cost UAVs that can be deployed over rough terrain, detect and locate poachers and communicate that information to park rangers. In short, it was designed to combat the technical problems that overcome the drones currently on the market.

The vast distances in Kruger NP would necessitate a huge expense in drone technology currently

Aliyah Pandolfi founder/director of the wcUAVc, says: “The drones that exist can’t have an impact, especially in the Kruger because of its size. There is no drone that can cope with those distances that reserves can purchase because of the high price. My key thinking was how to bring the cost down, because Kruger isn’t going to be able to afford hundreds of thousands of dollars.

“Our goal is to provide a fleet of drones that includes a strategic aircraft, as well as several tactical aircraft, for under $100,000. These would be the latest and greatest solutions, but they don’t exist right now.”

However, South Africa can be a fragile place, and with unemployment hovering at around 25 per cent there could be fears that jobs, already hard to come by, could be made obsolete by the new technology. Not so, says Pandolfi: “One thing that rangers need to understand is that drones are not meant to take their jobs away, they are meant to make it easier.

“I’d like to convey to rangers that this is going to help your job, and it’s going to allow you to do it better in terms of protecting wildlife.”

Being able to observe the bush in countries like Botswana from above could give rangers a big advantage

Poaching is a worldwide problem, which extends through nearly any area that has animals of worth. Luke Riggs, the owner of the Old House game lodge in Kasane, Botswana, says that he has even encountered the victims of poachers while out conducting game drives for his guests.

“When I did some hunting, I had a few incidents where we did find poached animals. That was just a matter of reporting it and spending a bit of time with the anti-poaching units. We tried our best to capture the poachers but had no success,” he says.

“With regards to the use of drones, this will be new to me. I have seen some military drones here in Botswana and I hear they were used mostly for anti-poaching, and I think it’s a great idea.”

Nepal has recently carried out trials to see what impact UAVs could have in helping them combat poaching, and the authorities there are very excited about the possibilities. General Krishna Acharya of Nepal's Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation said in a press release: “Nepal is committed to stopping wildlife crime, which is robbing Nepal of its natural resources, putting the lives of rangers and local communities at risk, and feeding into global criminal networks.

“Technologies like these non-lethal UAVs could give our park rangers a vital advantage against dangerously armed poachers.”

The main problem in the short term is the law, which currently works against those on the side of drones. At the moment, South African law prohibits the use of UAVs, but a review is underway with the hope that the law will be rewritten by March 2015.

Laws are similar around Africa, were there have been examples of governments grounding operations such as the Flying Donkey Challenge, which wants to develop drones that can fly heavy cargo over long distances, and the Ol Pejeta Conservancy’s wildlife surveillance drone.

There have only been 232 arrests of poachers in South Africa, which means that for every person arrested for poaching, three animals are slaughtered.

The law has been slow to catch up with technology, and is stalling an industry that could provide real help to not only catch poachers, but to tip the balance of risk and reward away from the people carrying out these acts and in the favour of the authorities – and most importantly, the animals.

A Bengal Tiger in Nepal

A Bengal Tiger in Nepal