Rhino Numbers and Census

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75352

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Numbers and Census

Agreed 1000%!!

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65876

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Numbers and Census

That's what you have always sustained

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65876

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Numbers and Census

Counting animals – the technology helping conservationists

Posted on April 11, 2022 by teamAG in the DECODING SCIENCE post series.

Knowing the size of animal populations in protected areas and reserves is at the heart of effective conservation strategies. Those in the know predict that one day,]wildlife will be counted by drones and AI.

Spotting animals is easier from a helicopter, but more expensive.

Counting wild animals can be a complicated process, particularly when estimating populations in some of Africa’s massive protected wild areas. Yet policymakers and conservationists need to make the best possible decisions regarding the programmes put in place to conserve certain species, especially where limited budgets are available.

Consistent analysis is vital to monitoring population trends over the years and proactively identifying potential threats and problems, rather than attempting to rectify population declines after the fact. Now scientists working with Save the Elephants and Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) have shown how technology can be used to make aerial population surveys more accurate.

A plane flies over a herd of elephants in Tsavo National Park during an aerial count

Typically, aerial wildlife counts are considered a more accurate method for counting animals, particularly in open spaces and where larger animal species are concerned. The standard method is to fly systematic reconnaissance flights over transects or along a survey line, with a ‘rear-seat-observer’ counting the number of animals within the transect or within a specific distance of the line. These numbers are used as sample units, and the population is extrapolated from there using various statistical methods. The researchers compared this method to a newly-devised ‘oblique-camera-count’ over Tsavo National Park. They concluded that human counters missed approximately 14% of the elephants, 60% of the giraffe, 48% of the zebra and 66% of the larger antelope. This, in turn, suggests that aerial counts have resulted in significantly undercounted wildlife populations.

Elephants from the air. This is the first study where continuous oblique imagery was acquired over complex terrestrial environments in Africa

This is not as a result of any negligence or lack of expertise on the part of the counters – animals can be hidden under dense vegetation, or cryptically coloured. Safety concerns mean that the plane has to maintain a specific altitude and speed, so counters only have a maximum of 7 seconds to count a particular area. Added to that is the inevitable variability as a result of aircraft type, ground speed, altitude, sample strip width and observer fatigue and the fact that using a helicopter to allow for more thorough counting is prohibitively expensive.

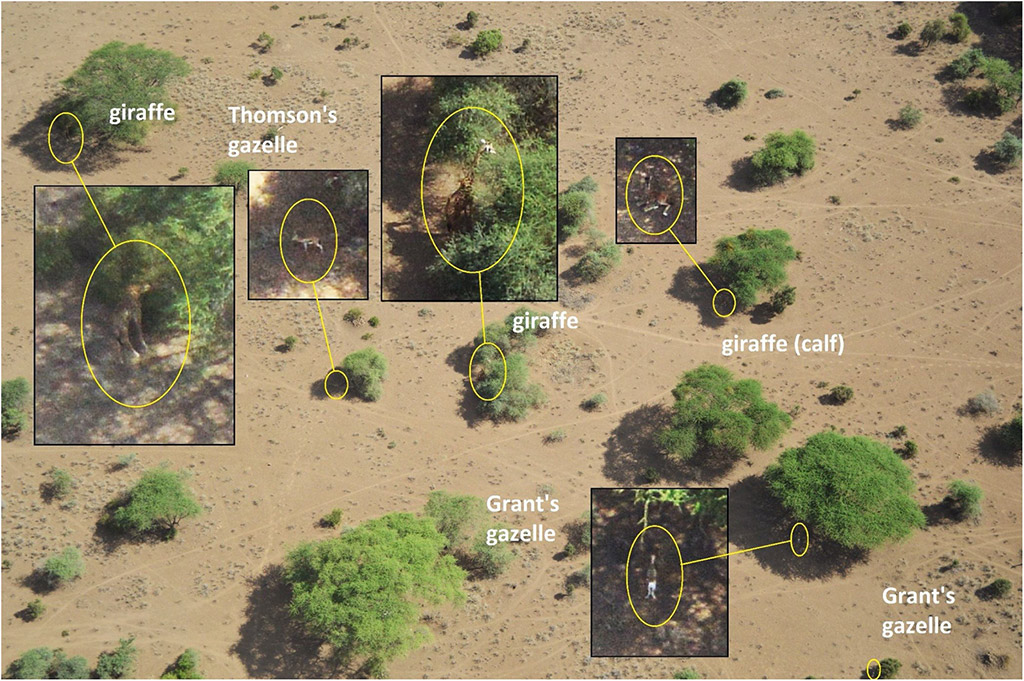

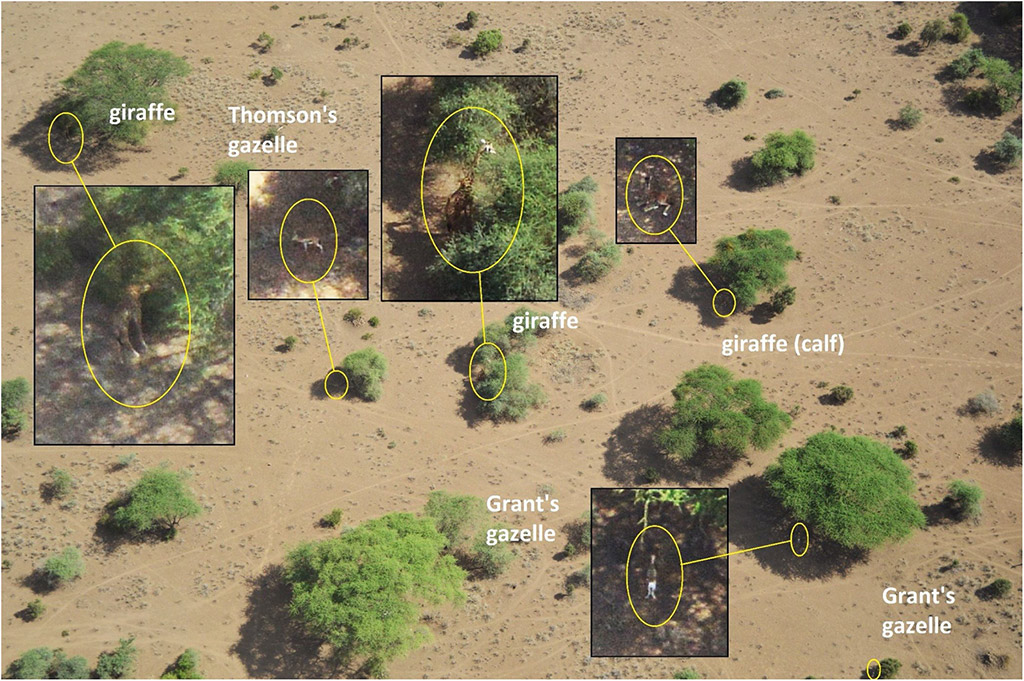

While these limitations had long been recognised, this is the first study of its kind where continuous oblique imagery (more suited to areas where animals might be resting under trees than imagery taken from directly overhead) was acquired over the complex terrestrial environments in Africa. Tsavo was chosen because wildlife counts had been planned for that period but it also presented challenges due to high ambient temperatures, strong winds and turbulence. The cameras were mounted to mimic the viewing perspective of the human counters. The images were later analysed by a team of interpreters who methodically worked through and enlarged thousands of images to identify and count animals.

At this stage, the authors of the study acknowledge that this process of image interpretation is labour intensive, as the interpreters went through over 200 images a day for nine months. Thus, they explain that this is just the starting point in the move towards more automated counting by machine learning where, at the very least, a software program can flag the potential presence of an animal. As technology improves, so will the ability to conduct aerial counts more accurately and cost-effectively.

These nine oryx are almost invisible in shadow conditions

As Save the Elephants has previously explained in an annual report, ever-changing technology has enormous implications for the conservation sphere. From specialised recognition software, scientists have already developed algorithms that recognise individual zebras and leopards. This information can only serve those tasked with protecting wilderness areas and the animals that call them home. Says Frank Pope, CEO of Save the Elephants: “Counting wildlife is critical for management but is expensive and surprisingly hard. Modern cameras mounted on aircraft can greatly improve accuracy, but counting the wildlife in the hundreds of thousands of images that result is impractical. Artificial intelligence holds the key to processing the images, and making these surveys cheaper as well as more precise. One day wildlife will be counted by drones and AI – what we’re doing is laying the foundations for that future.”

These animals would not be detected had the cameras been mounted vertically

Posted on April 11, 2022 by teamAG in the DECODING SCIENCE post series.

Knowing the size of animal populations in protected areas and reserves is at the heart of effective conservation strategies. Those in the know predict that one day,]wildlife will be counted by drones and AI.

Spotting animals is easier from a helicopter, but more expensive.

Counting wild animals can be a complicated process, particularly when estimating populations in some of Africa’s massive protected wild areas. Yet policymakers and conservationists need to make the best possible decisions regarding the programmes put in place to conserve certain species, especially where limited budgets are available.

Consistent analysis is vital to monitoring population trends over the years and proactively identifying potential threats and problems, rather than attempting to rectify population declines after the fact. Now scientists working with Save the Elephants and Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) have shown how technology can be used to make aerial population surveys more accurate.

A plane flies over a herd of elephants in Tsavo National Park during an aerial count

Typically, aerial wildlife counts are considered a more accurate method for counting animals, particularly in open spaces and where larger animal species are concerned. The standard method is to fly systematic reconnaissance flights over transects or along a survey line, with a ‘rear-seat-observer’ counting the number of animals within the transect or within a specific distance of the line. These numbers are used as sample units, and the population is extrapolated from there using various statistical methods. The researchers compared this method to a newly-devised ‘oblique-camera-count’ over Tsavo National Park. They concluded that human counters missed approximately 14% of the elephants, 60% of the giraffe, 48% of the zebra and 66% of the larger antelope. This, in turn, suggests that aerial counts have resulted in significantly undercounted wildlife populations.

Elephants from the air. This is the first study where continuous oblique imagery was acquired over complex terrestrial environments in Africa

This is not as a result of any negligence or lack of expertise on the part of the counters – animals can be hidden under dense vegetation, or cryptically coloured. Safety concerns mean that the plane has to maintain a specific altitude and speed, so counters only have a maximum of 7 seconds to count a particular area. Added to that is the inevitable variability as a result of aircraft type, ground speed, altitude, sample strip width and observer fatigue and the fact that using a helicopter to allow for more thorough counting is prohibitively expensive.

While these limitations had long been recognised, this is the first study of its kind where continuous oblique imagery (more suited to areas where animals might be resting under trees than imagery taken from directly overhead) was acquired over the complex terrestrial environments in Africa. Tsavo was chosen because wildlife counts had been planned for that period but it also presented challenges due to high ambient temperatures, strong winds and turbulence. The cameras were mounted to mimic the viewing perspective of the human counters. The images were later analysed by a team of interpreters who methodically worked through and enlarged thousands of images to identify and count animals.

At this stage, the authors of the study acknowledge that this process of image interpretation is labour intensive, as the interpreters went through over 200 images a day for nine months. Thus, they explain that this is just the starting point in the move towards more automated counting by machine learning where, at the very least, a software program can flag the potential presence of an animal. As technology improves, so will the ability to conduct aerial counts more accurately and cost-effectively.

These nine oryx are almost invisible in shadow conditions

As Save the Elephants has previously explained in an annual report, ever-changing technology has enormous implications for the conservation sphere. From specialised recognition software, scientists have already developed algorithms that recognise individual zebras and leopards. This information can only serve those tasked with protecting wilderness areas and the animals that call them home. Says Frank Pope, CEO of Save the Elephants: “Counting wildlife is critical for management but is expensive and surprisingly hard. Modern cameras mounted on aircraft can greatly improve accuracy, but counting the wildlife in the hundreds of thousands of images that result is impractical. Artificial intelligence holds the key to processing the images, and making these surveys cheaper as well as more precise. One day wildlife will be counted by drones and AI – what we’re doing is laying the foundations for that future.”

These animals would not be detected had the cameras been mounted vertically

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75352

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Numbers and Census

This is absolutely brilliant!

SP please take note!

SP please take note!

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65876

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Numbers and Census

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65876

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Numbers and Census

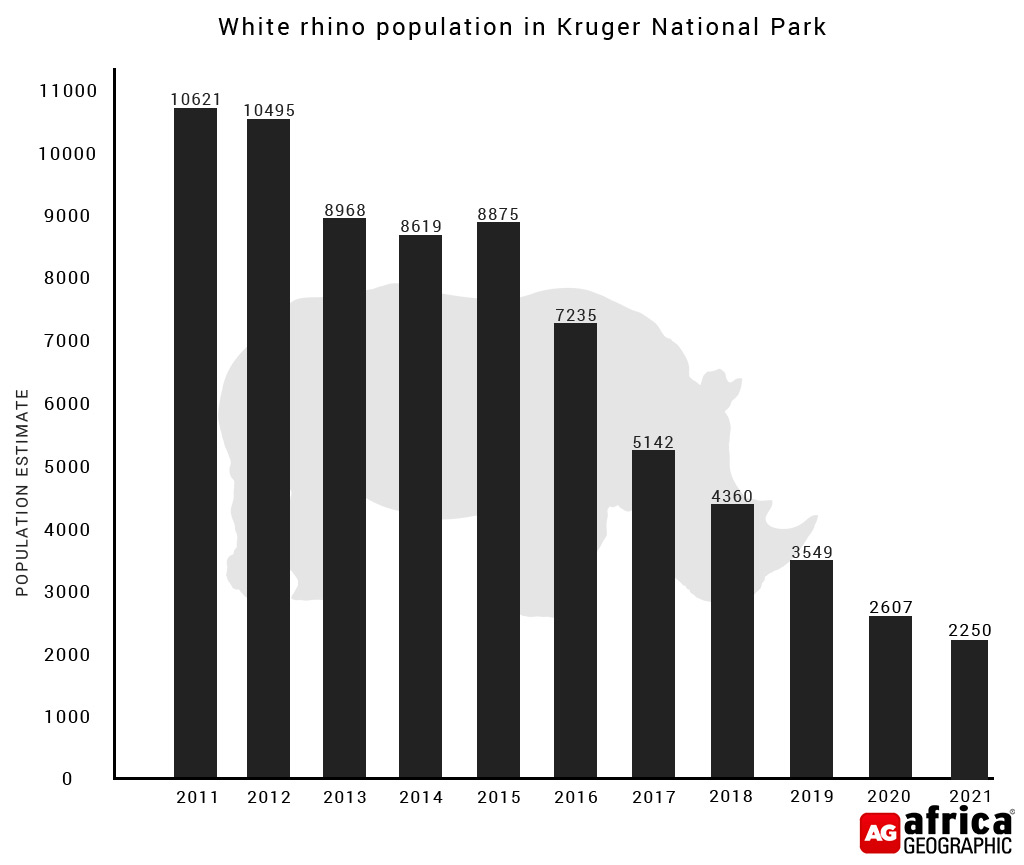

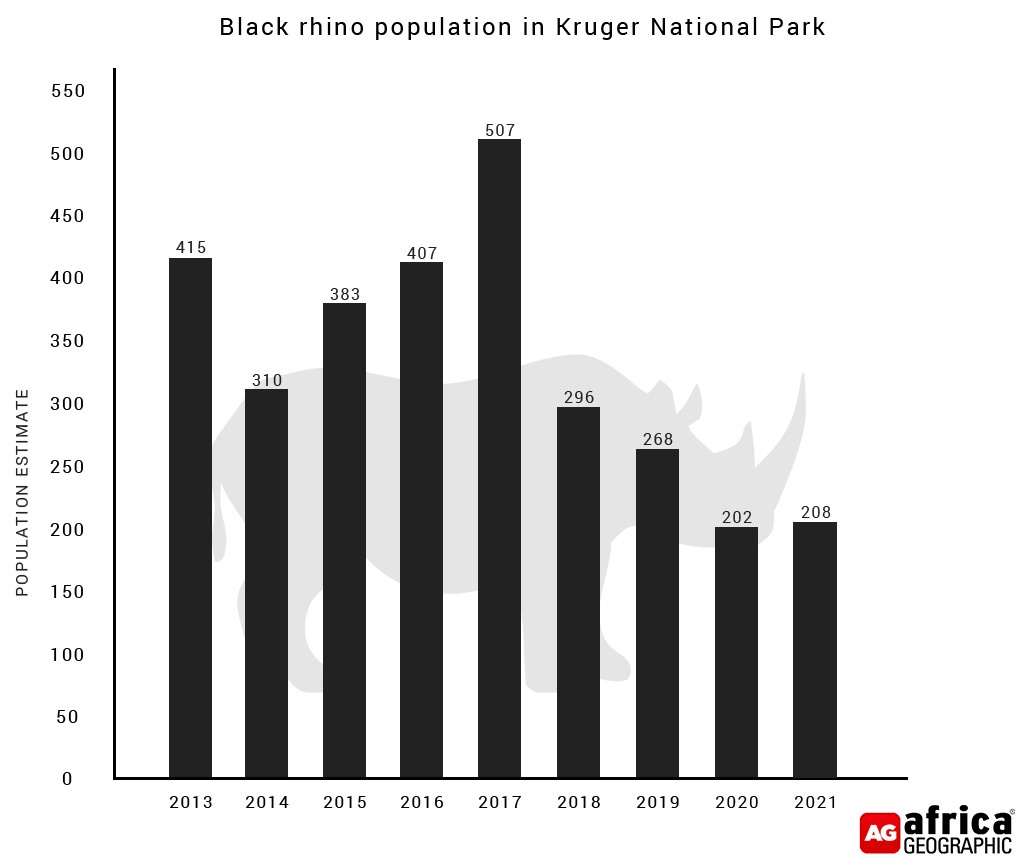

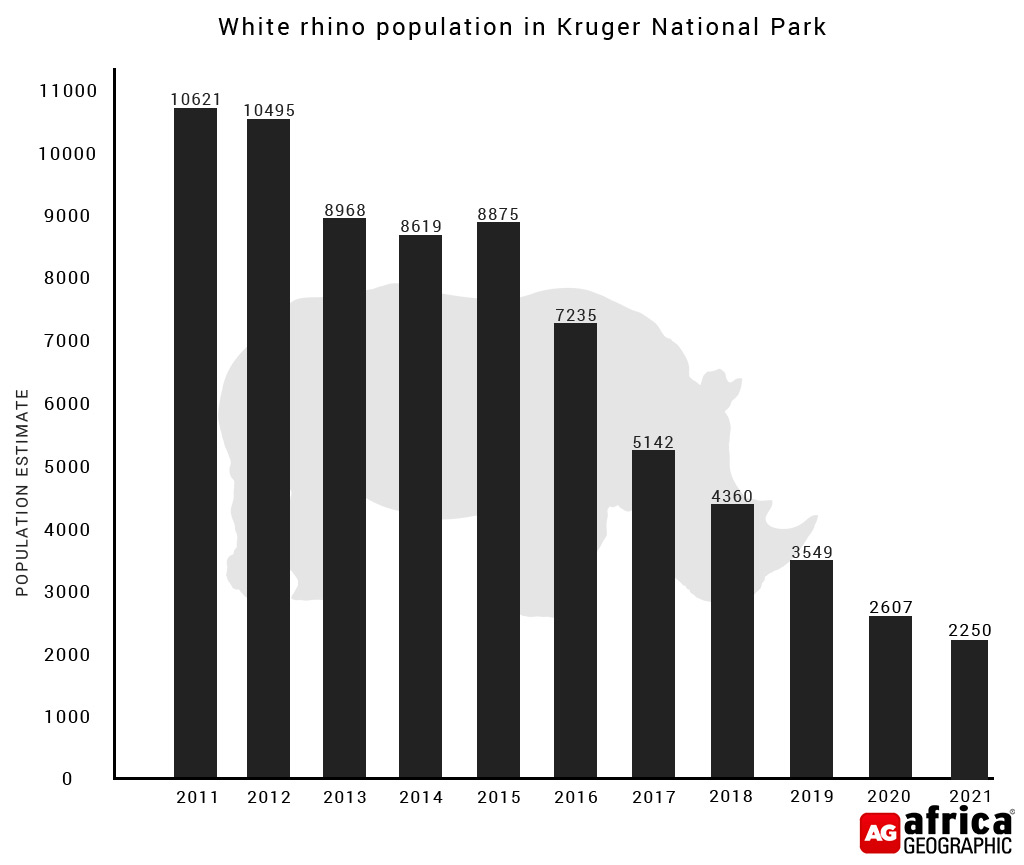

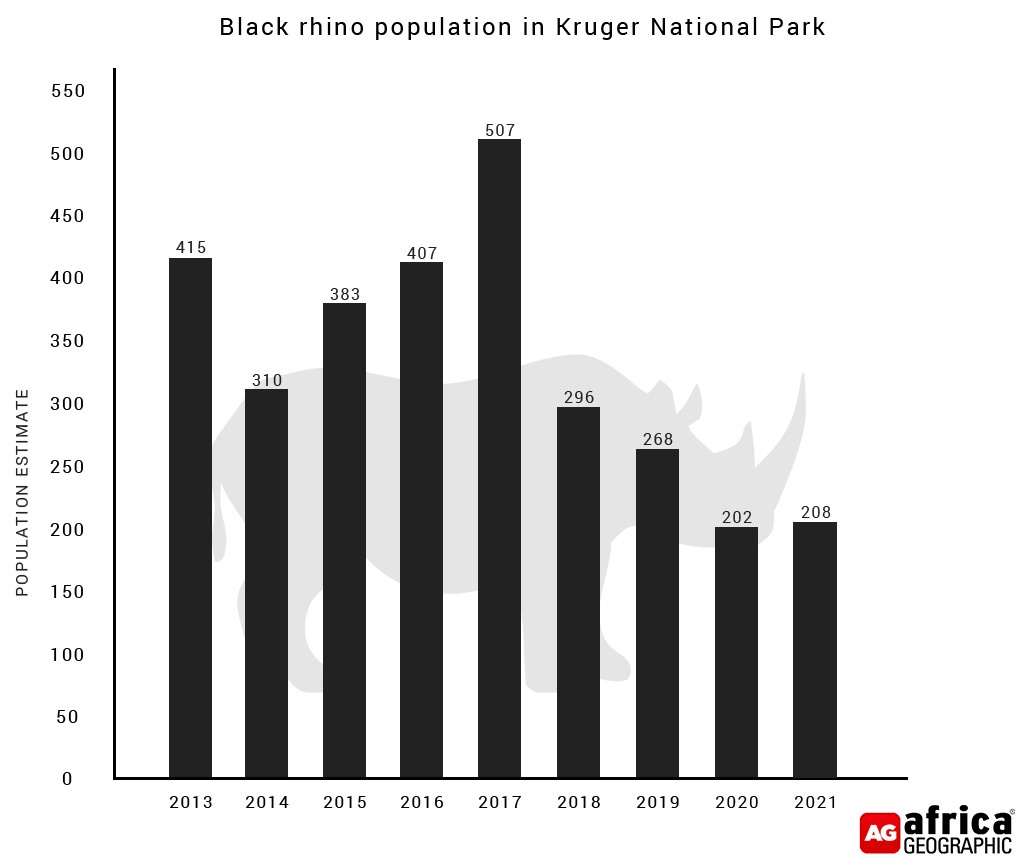

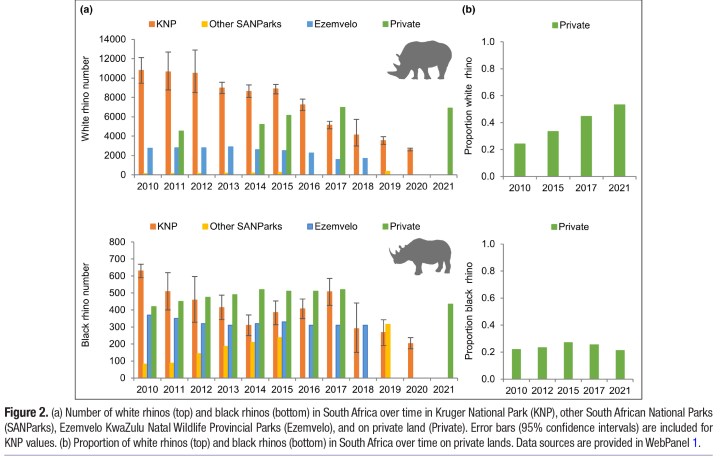

Another year of loss – an update on Kruger’s rhino populations

The latest stats from SANParks reveal an ongoing decline in rhino numbers

There are now an estimated 2,250 white rhinos remaining in Kruger – a 79% reduction since 2011. The estimated black rhino population now stands at 208 – a 50% reduction since 2013.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The SANParks Annual Report 2021/2022 confirms that rhino populations in the Kruger National Park have continued to decline, with a loss of 14.7% of white rhinos over the reporting period. However, black rhino populations were estimated to have increased by 2.9%.

Unlike previous Annual Reports, the 2021/2022 Report does not provide population estimates for either white or black rhinos within the park. However, Dr Sam Ferreira, Large Mammal Ecologist for SANParks and the Scientific Officer for the African Rhino Specialist Group, has confirmed the 2021 estimates for Africa Geographic. There were an estimated 2,250 (between 1,986 and 2,513*) white rhinos in Kruger in September 2021, compared to the 2,607 (between 2,475 and 2,752), counted in September 2020. For black rhinos, the 2021 survey estimated 208 (between 160-255) black rhinos occurring in Kruger, with confidence intervals overlapping the 2020 estimate of 202 (between 172 and 237). Ferreira confirmed that the results of the 2022 census are still being analysed.

*Editorial note: All population estimates are given a margin of error, as population counts over large areas carry inherent uncertainty. When calculating the percentage decline/increase, these margins of error are included in the statistical analysis.

The white rhino population in Kruger National Park continues to decline, while black rhino populations have seen a slight increase

The 2021/2022 Report confirms that 195 rhinos were poached in the Kruger National Park in 2021, a decrease from 247 in the previous year. (The most recent statistics from the Kruger National Park suggest that 82 rhinos were killed in the park in the first six months of 2022.) No rhinos have been lost in other SANParks-operated parks, namely Addo Elephant, Karoo, Mountain Zebra, Mokala, Mapungubwe and Marakele National Parks. These rhino populations have increased by 6.2%, and populations of south-western black rhinos (Diceros bicornis bicornis) outside of the Kruger have exceeded growth performance targets.

The Annual Report indicates that a new Rhino Strategy has been developed, focusing on “achieving thriving, growing rhino populations of a minimum size; and resilient communities across all stakeholders owning, valuing and benefitting from rhinos in a safe environment”. This will include strategic dehorning, range expansion and establishing “insurance populations”. Eight hundred and five rhinos have been dehorned in the Kruger National Park between 2021 and 2022, with a focus on cows and core protection zones. The report also references the establishment of rhino “strongholds” outside of the Kruger National Park to serve as sources for re-introductions in the long term.

However, as increased security and plummeting rhino numbers have made poaching more challenging in Kruger, there has been a concerning shift in focus to KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, where nearly 200 rhinos have been killed this year alone (mainly in Hluhluwe iMfolozi National Park), and to Namibia and Botswana.

Although the reduced poaching statistics are due primarily to there being fewer wild rhinos remaining, there is no question that the back-breaking work of passionate and dedicated SANParks employees is also a factor, and those that have contributed should be lauded for their efforts

The latest stats from SANParks reveal an ongoing decline in rhino numbers

There are now an estimated 2,250 white rhinos remaining in Kruger – a 79% reduction since 2011. The estimated black rhino population now stands at 208 – a 50% reduction since 2013.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The SANParks Annual Report 2021/2022 confirms that rhino populations in the Kruger National Park have continued to decline, with a loss of 14.7% of white rhinos over the reporting period. However, black rhino populations were estimated to have increased by 2.9%.

Unlike previous Annual Reports, the 2021/2022 Report does not provide population estimates for either white or black rhinos within the park. However, Dr Sam Ferreira, Large Mammal Ecologist for SANParks and the Scientific Officer for the African Rhino Specialist Group, has confirmed the 2021 estimates for Africa Geographic. There were an estimated 2,250 (between 1,986 and 2,513*) white rhinos in Kruger in September 2021, compared to the 2,607 (between 2,475 and 2,752), counted in September 2020. For black rhinos, the 2021 survey estimated 208 (between 160-255) black rhinos occurring in Kruger, with confidence intervals overlapping the 2020 estimate of 202 (between 172 and 237). Ferreira confirmed that the results of the 2022 census are still being analysed.

*Editorial note: All population estimates are given a margin of error, as population counts over large areas carry inherent uncertainty. When calculating the percentage decline/increase, these margins of error are included in the statistical analysis.

The white rhino population in Kruger National Park continues to decline, while black rhino populations have seen a slight increase

The 2021/2022 Report confirms that 195 rhinos were poached in the Kruger National Park in 2021, a decrease from 247 in the previous year. (The most recent statistics from the Kruger National Park suggest that 82 rhinos were killed in the park in the first six months of 2022.) No rhinos have been lost in other SANParks-operated parks, namely Addo Elephant, Karoo, Mountain Zebra, Mokala, Mapungubwe and Marakele National Parks. These rhino populations have increased by 6.2%, and populations of south-western black rhinos (Diceros bicornis bicornis) outside of the Kruger have exceeded growth performance targets.

The Annual Report indicates that a new Rhino Strategy has been developed, focusing on “achieving thriving, growing rhino populations of a minimum size; and resilient communities across all stakeholders owning, valuing and benefitting from rhinos in a safe environment”. This will include strategic dehorning, range expansion and establishing “insurance populations”. Eight hundred and five rhinos have been dehorned in the Kruger National Park between 2021 and 2022, with a focus on cows and core protection zones. The report also references the establishment of rhino “strongholds” outside of the Kruger National Park to serve as sources for re-introductions in the long term.

However, as increased security and plummeting rhino numbers have made poaching more challenging in Kruger, there has been a concerning shift in focus to KwaZulu-Natal in South Africa, where nearly 200 rhinos have been killed this year alone (mainly in Hluhluwe iMfolozi National Park), and to Namibia and Botswana.

Although the reduced poaching statistics are due primarily to there being fewer wild rhinos remaining, there is no question that the back-breaking work of passionate and dedicated SANParks employees is also a factor, and those that have contributed should be lauded for their efforts

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75352

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Numbers and Census

They do not really have a clue about how many rhino there are in Kruger, and no mention is made of staff involvement in poaching!

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65876

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Numbers and Census

Not a single poaching at world's largest reserve for endangered rhino - first since 1977

09.01.2023 - REUTERS

There was not a single rhino poached at the world's largest sanctuary.

Getty Images

No rhinos were poached last year in the world's largest reserve for the endangered great one-horned rhinoceros, India's Assam state, in what authorities said was the first time since 1977.

Filled with elephant-grass meadows, swampy lagoons, and dense forests, the Kaziranga National Park in northeast India's Assam is home to 2 200 rhinos, or two-thirds of their world population. It has attracted British royalty as well as cricket stars, but poaching had become a big concern.

Poachers killed more than 190 rhinos in Assam between 2000 and 2021 but none was killed last year, according to data shared by Assam Police with Reuters. The last time there was no poaching was in 1977.

A record 27 rhinos were killed in Assam each year in 2013 and 2014, the data showed, as poachers sought to sell their horns for thousands of dollars in East Asia where they are prized as medicine and jewelry.

Assam Police said 58 poachers were arrested last year, five injured and four killed.

"We need to keep the pressure on the poaching gangs," said Assam's special director general of police, Gyanendra Pratap Singh, who heads a task force to tackle poaching.

"We have to ensure that the graph of poaching stays flat at nil for a few years" until that becomes the norm, he said.

Authorities also plan to boost efforts to investigate those receiving poached rhino horns in other states and countries, he added.

Despite the poaching in Assam, the world population of the one-horned rhino has soared to around 3 700 from just around 200 at the turn of the 20th century, according to the global conservation group WWF.

Apart from India, they are also found in Nepal.

09.01.2023 - REUTERS

There was not a single rhino poached at the world's largest sanctuary.

Getty Images

No rhinos were poached last year in the world's largest reserve for the endangered great one-horned rhinoceros, India's Assam state, in what authorities said was the first time since 1977.

Filled with elephant-grass meadows, swampy lagoons, and dense forests, the Kaziranga National Park in northeast India's Assam is home to 2 200 rhinos, or two-thirds of their world population. It has attracted British royalty as well as cricket stars, but poaching had become a big concern.

Poachers killed more than 190 rhinos in Assam between 2000 and 2021 but none was killed last year, according to data shared by Assam Police with Reuters. The last time there was no poaching was in 1977.

A record 27 rhinos were killed in Assam each year in 2013 and 2014, the data showed, as poachers sought to sell their horns for thousands of dollars in East Asia where they are prized as medicine and jewelry.

Assam Police said 58 poachers were arrested last year, five injured and four killed.

"We need to keep the pressure on the poaching gangs," said Assam's special director general of police, Gyanendra Pratap Singh, who heads a task force to tackle poaching.

"We have to ensure that the graph of poaching stays flat at nil for a few years" until that becomes the norm, he said.

Authorities also plan to boost efforts to investigate those receiving poached rhino horns in other states and countries, he added.

Despite the poaching in Assam, the world population of the one-horned rhino has soared to around 3 700 from just around 200 at the turn of the 20th century, according to the global conservation group WWF.

Apart from India, they are also found in Nepal.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75352

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Numbers and Census

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65876

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Rhino Numbers and Census

Private and communal lands conserve half of Africa’s rhinos, and call for ‘adaptive policies’

White rhino seen grazing at a private game reserve in North West Province, near Brits, on Tuesday, 10 April 2012. (Photo: Nadine Hutton/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

By Ed Stoddard | 16 Jan 2023

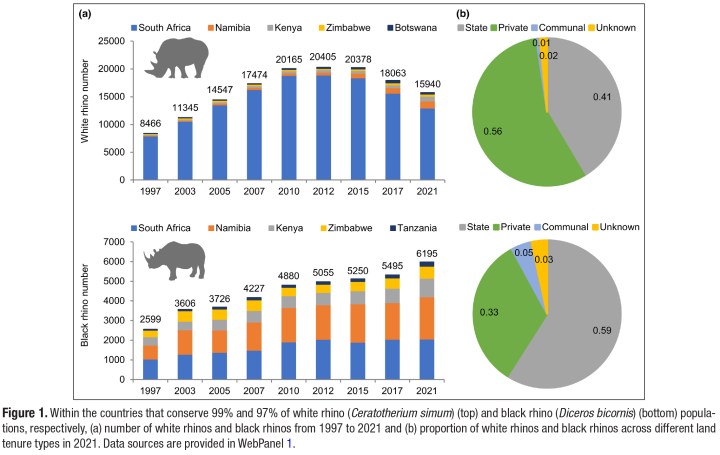

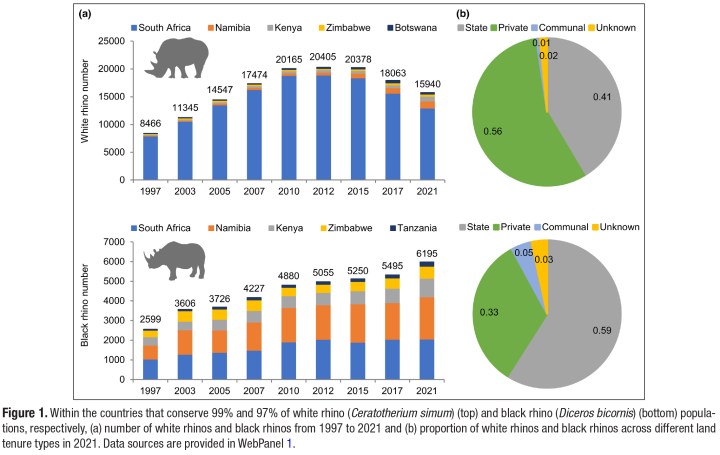

Private and communal lands now conserve at least 50% of Africa’s rhinos, according to a newly published paper in journal ‘Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment’, highlighting the need for ‘adaptive policies’ to build on this success. These trends have policy implications as debates rage about rhino-horn trade and trophy hunting.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

One of the most significant trends in megafauna conservation in recent years has been the growing numbers of rhinos on private ranches and reserves in South Africa, at a time when populations in state-run parks have plunged in the face of unrelenting poaching to feed Asian demand for horn.

In the past few years, the number of privately owned rhinos in South Africa has exceeded the number in state hands, as a result. And private populations continue to grow while state-managed populations, notably in the Kruger National Park, maintain their dramatic decline.

A newly published paper in peer-reviewed journal ‘Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment’ has cast a wider net around the issue, looking beyond South Africa and including populations found on communal land in Africa.

“We aggregated African rhino population data, highlighting the growing role of private and community rhino custodians, who likely now conserve > 50% of Africa’s rhinos,” says the study, lead-authored by Hayley Clements of the Universities of Helsinki and Stellenbosch. Dave Balfour, a widely regarded South African expert on rhino conservation, is one of the co-authors.

“As the role of private and community custodianship becomes increasingly central to the protection of Africa’s remaining rhinos, its resilience must be strengthened through implementation of adaptive policies that incentivise rhino conservation,” they write.

Incentives are clearly lacking and policies are needed to address the realities on the ground.

The situation in South Africa’s government-run parks is nothing short of catastrophic, and is emblematic of the ANC’s failing state.

“Until the past decade, by far the largest populations of South Africa’s rhinos were found in the state-run Kruger National Park. The park has, however, become a poaching hotspot, with figures released in 2021 signalling 76% and 68% declines in the white rhino and black rhino populations over the past decade, respectively,” the authors note.

A white rhino stumbles at the effects of a tranquiliser dart before having its horn trimmed, at the ranch of rhino breeder John Hume, in the North West Province. In a bid to prevent poaching and conserve the different species of rhino, the horns of animals are regularly trimmed, a controversial decision where off-cuts are placed on sale at auction. (Photo: Leon Neal/Getty Images)

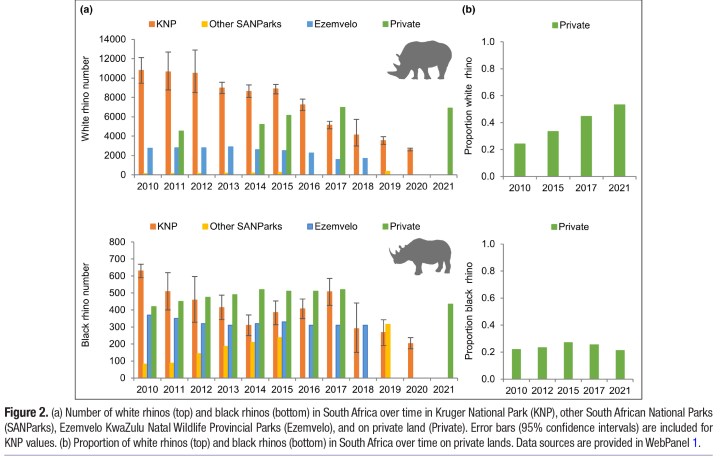

“Over the same decade, the estimated number of white rhinos on private land in South Africa has steadily increased. As a result of these divergent rhino population trends on state and private lands, the proportion of the country’s white rhinos on private land increased from 25% in 2010, to 53% in 2021. This means that, collectively, private landholders in South Africa now support the largest number of white rhinos on the continent. A lower but still substantial proportion (~25% over the past decade) of South Africa’s black rhinos are conserved on privately held lands.”

This is partly related to surging security costs, which the South African state — saddled with a growing debt burden and social needs, and a woeful track record of putting tax revenue to good use — is simply incapable of meeting.

“We could find only one published figure for what SANParks spends toward fulfilling their stated objective of ‘Sustainable rhino populations monitored and increased’: R25.6-million or R8,600 per rhino in 2020 (SANParks 2021). Even if this is an extremely conservative figure, it is markedly less than the average spent by private properties on rhino security: R28,600 per rhino in 2017.”

Prohibitive security price tag

One of the consequences has been a concentration of private rhino ownership as smaller players find the security price tag prohibitive.

“In aggregate, across the African continent, the proportion of white rhinos and black rhinos on private land in 2021 was over one-half and one-third, respectively. In addition, 5% of black rhinos were held on communal land, largely in Namibia and South Africa. In light of the ongoing rhino declines in Kruger National Park, contributions of private and communal landholders to rhino custodianship are likely to be growing,” the authors write.

Private wildlife ranches in South Africa account for 17% of the country’s land area now, twice that of state parks, the study says. In Kenya, communal and private conservancies support 65% of the country’s wildlife on just 11% of its land surface.

In Zimbabwe in 2018, 88% of black rhinos and 76% of white rhino populations were found on private land. In Namibia, 75% of the white rhino population is on private reserves, and 7% of its black rhino population roams in community conservancies.

In total, the study estimated the total African white rhino population in 2021 at just under 16,000 — versus more than 20,000 in 2012 — with almost 8,000 in the hands of private owners in South Africa, versus less than 5,000 in 2012.

A graph showing the importance of private and communal lands to the sustainable conservation of Africa’s rhino. (Supplied)

“Over the past century, private and communal wildlife ranches and conservancies have emerged as competitive land use in several southern and eastern African countries. Revenues (and therefore livelihoods) in these areas are generated through wildlife-based tourism and/or consumptive wildlife uses, including hunting for meat or trophies, wildlife sales, and meat sales. Such land uses are dependent on policies that enable landholders to generate wildlife-based revenues that are competitive in relation to alternative land use options such as agriculture.”

To that end, the authors raise some policy suggestions, while cautioning about the practice of “intensive management”, which often entails controlled breeding and fenced enclosures. Whether or not this makes a population “less wild” as the paper asserts, is a source of debate.

The vexed issue of loosening restrictions on the global ban in rhino horn under the auspices of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is one policy issue the authors address.

Context-appropriate conservation

“It has been proposed that a more appropriate first measure for conserving threatened species could be the development of context-appropriate conservation programs in partnership with local people, as opposed to the blunt instrument top-down approach of an international trade ban.”

In short, perhaps listen to what local people on the ground in Africa have to say, instead of middle-class western suburbanites spouting outrage on Twitter or at cocktail parties.

Then there is the emotionally charged issue of trophy hunting.

“Also at the international scale, there is growing pressure to ban trophy hunting, which was an instrumental activity in enabling the recovery of African rhino populations and is currently a key revenue source to fund rhino protection. As with trade regulations, consideration of the local contexts in which trophy hunting takes place is essential, as are the likely implications of restrictions on hunting for both local livelihoods and rhino conservation,” the authors note.

There is staunch opposition among some conservationists – a very vocal if perhaps growing minority – to “consumptive utilisation” of wildlife as a conservation tool. And some of the arguments against rhino horn trade – notably that it will fuel demand and trigger more poaching – are not without merit, while also being open to debate.

Opposition to trophy hunting is rooted in animal welfare concerns and an aversion to the idea of humans taking pleasure from blood sports. Even if you disagree with the sentiment, it is an understandable stance. But it fails to even consider the conservation benefits of hunting, not least because the past time is regarded as beyond the pale. This has triggered stale debates such as comparisons with game viewing tourism, which has a far bigger carbon and environmental footprint and is far more intrusive. And sometimes ends with dead animals anyway.

But many current measures that thwart consumptive use are clearly not working, and so why not try “adaptive policies” to provide incentives for conservation strategies that are actually working?

A second graph showing the importance of private and communal lands to the sustainable conservation of Africa’s rhino. (Supplied)

Moving beyond trade and hunting, the authors have some sensible suggestions, including incentives to address the “intense management” issue.

They say “it is imperative that future policy enables new incentives that encourage rhino conservation in more extensive” systems. “For example, could landholders that conserve rhinos in extensive systems qualify for a more favourable tax structure? Could they be eligible for carbon credits or rhino bonds, given the role of rhinos in carbon cycling? Could they receive certifications for extensive management that increase the value of their wildlife-based tourism and hunting offerings?”

Crowdfunding to support big animal conservation projects is another option the authors raise, pointing to Wildlife Credits, a Namibian initiative that “crowdfunds donations to support payments to communal conservancies linked to conservation performance, including rhino sightings and monitoring”.

It’s all food for thought. If rhino populations are thriving on private and communal lands and getting shot out on state reserves, why not encourage what works? One danger, of course, is if poachers will increasingly turn to such settings, as populations in state parks get wiped out. There is also evidence that horn stockpiles, both private and government, are “leaking” product to illicit markets.

With all this in mind, fresh approaches are urgently needed. DM/OBP

White rhino seen grazing at a private game reserve in North West Province, near Brits, on Tuesday, 10 April 2012. (Photo: Nadine Hutton/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

By Ed Stoddard | 16 Jan 2023

Private and communal lands now conserve at least 50% of Africa’s rhinos, according to a newly published paper in journal ‘Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment’, highlighting the need for ‘adaptive policies’ to build on this success. These trends have policy implications as debates rage about rhino-horn trade and trophy hunting.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

One of the most significant trends in megafauna conservation in recent years has been the growing numbers of rhinos on private ranches and reserves in South Africa, at a time when populations in state-run parks have plunged in the face of unrelenting poaching to feed Asian demand for horn.

In the past few years, the number of privately owned rhinos in South Africa has exceeded the number in state hands, as a result. And private populations continue to grow while state-managed populations, notably in the Kruger National Park, maintain their dramatic decline.

A newly published paper in peer-reviewed journal ‘Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment’ has cast a wider net around the issue, looking beyond South Africa and including populations found on communal land in Africa.

“We aggregated African rhino population data, highlighting the growing role of private and community rhino custodians, who likely now conserve > 50% of Africa’s rhinos,” says the study, lead-authored by Hayley Clements of the Universities of Helsinki and Stellenbosch. Dave Balfour, a widely regarded South African expert on rhino conservation, is one of the co-authors.

“As the role of private and community custodianship becomes increasingly central to the protection of Africa’s remaining rhinos, its resilience must be strengthened through implementation of adaptive policies that incentivise rhino conservation,” they write.

Incentives are clearly lacking and policies are needed to address the realities on the ground.

The situation in South Africa’s government-run parks is nothing short of catastrophic, and is emblematic of the ANC’s failing state.

“Until the past decade, by far the largest populations of South Africa’s rhinos were found in the state-run Kruger National Park. The park has, however, become a poaching hotspot, with figures released in 2021 signalling 76% and 68% declines in the white rhino and black rhino populations over the past decade, respectively,” the authors note.

A white rhino stumbles at the effects of a tranquiliser dart before having its horn trimmed, at the ranch of rhino breeder John Hume, in the North West Province. In a bid to prevent poaching and conserve the different species of rhino, the horns of animals are regularly trimmed, a controversial decision where off-cuts are placed on sale at auction. (Photo: Leon Neal/Getty Images)

“Over the same decade, the estimated number of white rhinos on private land in South Africa has steadily increased. As a result of these divergent rhino population trends on state and private lands, the proportion of the country’s white rhinos on private land increased from 25% in 2010, to 53% in 2021. This means that, collectively, private landholders in South Africa now support the largest number of white rhinos on the continent. A lower but still substantial proportion (~25% over the past decade) of South Africa’s black rhinos are conserved on privately held lands.”

This is partly related to surging security costs, which the South African state — saddled with a growing debt burden and social needs, and a woeful track record of putting tax revenue to good use — is simply incapable of meeting.

“We could find only one published figure for what SANParks spends toward fulfilling their stated objective of ‘Sustainable rhino populations monitored and increased’: R25.6-million or R8,600 per rhino in 2020 (SANParks 2021). Even if this is an extremely conservative figure, it is markedly less than the average spent by private properties on rhino security: R28,600 per rhino in 2017.”

Prohibitive security price tag

One of the consequences has been a concentration of private rhino ownership as smaller players find the security price tag prohibitive.

“In aggregate, across the African continent, the proportion of white rhinos and black rhinos on private land in 2021 was over one-half and one-third, respectively. In addition, 5% of black rhinos were held on communal land, largely in Namibia and South Africa. In light of the ongoing rhino declines in Kruger National Park, contributions of private and communal landholders to rhino custodianship are likely to be growing,” the authors write.

Private wildlife ranches in South Africa account for 17% of the country’s land area now, twice that of state parks, the study says. In Kenya, communal and private conservancies support 65% of the country’s wildlife on just 11% of its land surface.

In Zimbabwe in 2018, 88% of black rhinos and 76% of white rhino populations were found on private land. In Namibia, 75% of the white rhino population is on private reserves, and 7% of its black rhino population roams in community conservancies.

In total, the study estimated the total African white rhino population in 2021 at just under 16,000 — versus more than 20,000 in 2012 — with almost 8,000 in the hands of private owners in South Africa, versus less than 5,000 in 2012.

A graph showing the importance of private and communal lands to the sustainable conservation of Africa’s rhino. (Supplied)

“Over the past century, private and communal wildlife ranches and conservancies have emerged as competitive land use in several southern and eastern African countries. Revenues (and therefore livelihoods) in these areas are generated through wildlife-based tourism and/or consumptive wildlife uses, including hunting for meat or trophies, wildlife sales, and meat sales. Such land uses are dependent on policies that enable landholders to generate wildlife-based revenues that are competitive in relation to alternative land use options such as agriculture.”

To that end, the authors raise some policy suggestions, while cautioning about the practice of “intensive management”, which often entails controlled breeding and fenced enclosures. Whether or not this makes a population “less wild” as the paper asserts, is a source of debate.

The vexed issue of loosening restrictions on the global ban in rhino horn under the auspices of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) is one policy issue the authors address.

Context-appropriate conservation

“It has been proposed that a more appropriate first measure for conserving threatened species could be the development of context-appropriate conservation programs in partnership with local people, as opposed to the blunt instrument top-down approach of an international trade ban.”

In short, perhaps listen to what local people on the ground in Africa have to say, instead of middle-class western suburbanites spouting outrage on Twitter or at cocktail parties.

Then there is the emotionally charged issue of trophy hunting.

“Also at the international scale, there is growing pressure to ban trophy hunting, which was an instrumental activity in enabling the recovery of African rhino populations and is currently a key revenue source to fund rhino protection. As with trade regulations, consideration of the local contexts in which trophy hunting takes place is essential, as are the likely implications of restrictions on hunting for both local livelihoods and rhino conservation,” the authors note.

There is staunch opposition among some conservationists – a very vocal if perhaps growing minority – to “consumptive utilisation” of wildlife as a conservation tool. And some of the arguments against rhino horn trade – notably that it will fuel demand and trigger more poaching – are not without merit, while also being open to debate.

Opposition to trophy hunting is rooted in animal welfare concerns and an aversion to the idea of humans taking pleasure from blood sports. Even if you disagree with the sentiment, it is an understandable stance. But it fails to even consider the conservation benefits of hunting, not least because the past time is regarded as beyond the pale. This has triggered stale debates such as comparisons with game viewing tourism, which has a far bigger carbon and environmental footprint and is far more intrusive. And sometimes ends with dead animals anyway.

But many current measures that thwart consumptive use are clearly not working, and so why not try “adaptive policies” to provide incentives for conservation strategies that are actually working?

A second graph showing the importance of private and communal lands to the sustainable conservation of Africa’s rhino. (Supplied)

Moving beyond trade and hunting, the authors have some sensible suggestions, including incentives to address the “intense management” issue.

They say “it is imperative that future policy enables new incentives that encourage rhino conservation in more extensive” systems. “For example, could landholders that conserve rhinos in extensive systems qualify for a more favourable tax structure? Could they be eligible for carbon credits or rhino bonds, given the role of rhinos in carbon cycling? Could they receive certifications for extensive management that increase the value of their wildlife-based tourism and hunting offerings?”

Crowdfunding to support big animal conservation projects is another option the authors raise, pointing to Wildlife Credits, a Namibian initiative that “crowdfunds donations to support payments to communal conservancies linked to conservation performance, including rhino sightings and monitoring”.

It’s all food for thought. If rhino populations are thriving on private and communal lands and getting shot out on state reserves, why not encourage what works? One danger, of course, is if poachers will increasingly turn to such settings, as populations in state parks get wiped out. There is also evidence that horn stockpiles, both private and government, are “leaking” product to illicit markets.

With all this in mind, fresh approaches are urgently needed. DM/OBP

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge