State of the World's Wildlife: Towards Mass Extinction?

- Mel

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 26737

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Germany

- Location: Föhr

- Contact:

Re: World on track to lose two-thirds of wild animals by 2020

Because people don't heed to early warnings... that's how humans operate...

God put me on earth to accomplish a certain amount of things. Right now I'm so far behind that I'll never die.

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65862

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Hundreds more species under threat of extinction than previously thought, scientists say

'This indicates that urgent reassessment is needed of the current statuses of animal species’

Josh Gabbatiss Science Correspondent @josh_gabbatiss

Thursday 17 January 2019 08:15

The current Red List of Threatened Species covers over 90,000 species, and keeping track of them is difficult ( Getty )

Around 600 animal species may be inaccurately classified as non-threatened under current measurements, according to a new study.

Over 100 that were previously considered impossible to assess by experts who compile the official Red List of Threatened Species could also face extinction unless action is taken.

Scientists devised a new method based on sophisticated statistical models to assess the status of species for which data is lacking.

This included information about the landscapes animals are known to inhabit, and their ability to cope with and move through disrupted habitats.

While human pressures from deforestation to climate change push many species towards extinction, there are still vast swathes of the animal and plant kingdoms that remain largely unknown.

Dr Santini said he hoped this new strategy can be used as an early warning system to highlight species that require urgent attention.

The results, which the team says can be used to complement traditional IUCN methods, were published in the journal Conservation Biology.

Josh Gabbatiss Science Correspondent @josh_gabbatiss

Thursday 17 January 2019 08:15

The current Red List of Threatened Species covers over 90,000 species, and keeping track of them is difficult ( Getty )

Around 600 animal species may be inaccurately classified as non-threatened under current measurements, according to a new study.

Over 100 that were previously considered impossible to assess by experts who compile the official Red List of Threatened Species could also face extinction unless action is taken.

Scientists devised a new method based on sophisticated statistical models to assess the status of species for which data is lacking.

This included information about the landscapes animals are known to inhabit, and their ability to cope with and move through disrupted habitats.

While human pressures from deforestation to climate change push many species towards extinction, there are still vast swathes of the animal and plant kingdoms that remain largely unknown.

Dr Santini said he hoped this new strategy can be used as an early warning system to highlight species that require urgent attention.

The results, which the team says can be used to complement traditional IUCN methods, were published in the journal Conservation Biology.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65862

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

1 million species risk extinction due to humans – draft U.N. report

2019-04-25 22:53

https://youtu.be/v-z6Z-VV0kc

Up to one million species face extinction due to human influence, according to a draft UN report obtained by AFP that painstakingly catalogues how humanity has undermined the natural resources upon which its very survival depends.

The report says the accelerating loss of clean air, drinkable water, CO2-absorbing forests, pollinating insects, protein-rich fish and storm-blocking mangroves poses no less of a threat than climate change. Full story: https://www.rappler.com/science-natur...

https://www.news24.com/Green/News/watch ... t-20190425

https://youtu.be/v-z6Z-VV0kc

Up to one million species face extinction due to human influence, according to a draft UN report obtained by AFP that painstakingly catalogues how humanity has undermined the natural resources upon which its very survival depends.

The report says the accelerating loss of clean air, drinkable water, CO2-absorbing forests, pollinating insects, protein-rich fish and storm-blocking mangroves poses no less of a threat than climate change. Full story: https://www.rappler.com/science-natur...

https://www.news24.com/Green/News/watch ... t-20190425

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65862

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: 1 million species risk extinction due to humans – draft U.N. report

Here we go again: Earth's major 'mass extinctions'

2019-05-06 14:28 - AFP

Whether humanity has pushed the planet into a "mass extinction" event may be a matter of definition, but by any measure the rate at which life-forms are disappearing is deeply alarming, scientists say.

"In each of the five previous mass extinctions, we lost about 75% of species," said Robert Watson, head of the UN science panel on biodiversity, which unveiled a grim assessment of the state of Nature on Monday.

Over the last several centuries Earth has lost about 2%, and so – by that criterion – remains far below the threshold, he told AFP.

But if one looks instead at the rate at which species are dying off, the picture becomes bleaker.

Currently the pace of extinctions is up to several hundred times greater than the average over the last ten million years, the new report concluded. At that rate, we could hit the 75% mark within a couple of hundred years.

Here are Earth's biggest die-offs over the last half-billion years, each showing up in the fossil record at the boundary between geological periods.

Ordovician extinction

When: About 445 million years ago

Species lost: 60-70%

Likely cause: Short but intense ice age

Most life at this time was in the oceans. It is thought that the rapid, planet-wide formation of glaciers froze much of the world's water, causing sea levels to fall sharply. Marine organisms such as sponges and algae, along with primitive snails, clams, cephalopods and jawless fish called ostracoderms, all suffered as a consequence.

Devonian extinction

When: About 375-360 million years ago

Species lost: Up to 75%

Likely cause: Oxygen depletion in the ocean

Again, ocean organisms were hardest hit. Fluctuations in sea level, climate change, and asteroid strikes are all suspects. One theory holds that the massive expansion of plant life on land released compounds that caused oxygen depletion in shallow waters. Armoured, bottom-dwelling marine creatures called trilobites were among the many victims, though some species survived.

Permian extinction

When: About 252 million years ago

Species lost: 95%

Possible causes: Asteroid impact, volcanic activity

The mother of all extinctions, the "Great Dying" devastated ocean and land life alike, and is the only event to have nearly wiped out insects as well. Some scientists say the die-off occurred over millions of years, while others argue it was highly concentrated in a 200 000-year period.

In the sea, trilobites that had survived the last two wipeouts finally succumbed, along with some sharks and bony fishes. On land, massive reptiles known as moschops met their demise. Asteroid impacts, methane release and sea level fluctuations have all been blamed.

Triassic extinction

When: About 200 million years ago

Species lost: 70-80%

Likely causes: Multiple, still debated

The mysterious Triassic die-out eliminated a vast menagerie of large land animals, including most archosaurs, a diverse group that gave rise to dinosaurs, and whose living relatives today are birds and crocodiles. Most big amphibians were also eliminated.

One theory points to massive lava eruptions during the breakup of the super-continent Pangea, which might have released huge amounts of carbon dioxide, causing runaway global warming. Other scientists suspect asteroid strikes are to blame, but matching craters have yet to be found.

Cretaceous extinction

When: About 66 million years ago

Species lost: 75%

Likely cause: Asteroid strike

A space rock impact is suspect No. 1 for the extinction event that wiped out the world's non-avian dinosaurs, from T-Rex to the three-horned Triceratops. A huge crater off Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula supports the asteroid hypothesis.

But most mammals, turtles, crocodiles and frogs survived, along with birds as well as most sea life, including sharks, starfish and sea urchins. With dinosaurs out of the way, mammals flourished, eventually giving rise to the species – Homo sapiens – that has sparked fear of the sixth mass extinction.

2019-05-06 14:28 - AFP

Whether humanity has pushed the planet into a "mass extinction" event may be a matter of definition, but by any measure the rate at which life-forms are disappearing is deeply alarming, scientists say.

"In each of the five previous mass extinctions, we lost about 75% of species," said Robert Watson, head of the UN science panel on biodiversity, which unveiled a grim assessment of the state of Nature on Monday.

Over the last several centuries Earth has lost about 2%, and so – by that criterion – remains far below the threshold, he told AFP.

But if one looks instead at the rate at which species are dying off, the picture becomes bleaker.

Currently the pace of extinctions is up to several hundred times greater than the average over the last ten million years, the new report concluded. At that rate, we could hit the 75% mark within a couple of hundred years.

Here are Earth's biggest die-offs over the last half-billion years, each showing up in the fossil record at the boundary between geological periods.

Ordovician extinction

When: About 445 million years ago

Species lost: 60-70%

Likely cause: Short but intense ice age

Most life at this time was in the oceans. It is thought that the rapid, planet-wide formation of glaciers froze much of the world's water, causing sea levels to fall sharply. Marine organisms such as sponges and algae, along with primitive snails, clams, cephalopods and jawless fish called ostracoderms, all suffered as a consequence.

Devonian extinction

When: About 375-360 million years ago

Species lost: Up to 75%

Likely cause: Oxygen depletion in the ocean

Again, ocean organisms were hardest hit. Fluctuations in sea level, climate change, and asteroid strikes are all suspects. One theory holds that the massive expansion of plant life on land released compounds that caused oxygen depletion in shallow waters. Armoured, bottom-dwelling marine creatures called trilobites were among the many victims, though some species survived.

Permian extinction

When: About 252 million years ago

Species lost: 95%

Possible causes: Asteroid impact, volcanic activity

The mother of all extinctions, the "Great Dying" devastated ocean and land life alike, and is the only event to have nearly wiped out insects as well. Some scientists say the die-off occurred over millions of years, while others argue it was highly concentrated in a 200 000-year period.

In the sea, trilobites that had survived the last two wipeouts finally succumbed, along with some sharks and bony fishes. On land, massive reptiles known as moschops met their demise. Asteroid impacts, methane release and sea level fluctuations have all been blamed.

Triassic extinction

When: About 200 million years ago

Species lost: 70-80%

Likely causes: Multiple, still debated

The mysterious Triassic die-out eliminated a vast menagerie of large land animals, including most archosaurs, a diverse group that gave rise to dinosaurs, and whose living relatives today are birds and crocodiles. Most big amphibians were also eliminated.

One theory points to massive lava eruptions during the breakup of the super-continent Pangea, which might have released huge amounts of carbon dioxide, causing runaway global warming. Other scientists suspect asteroid strikes are to blame, but matching craters have yet to be found.

Cretaceous extinction

When: About 66 million years ago

Species lost: 75%

Likely cause: Asteroid strike

A space rock impact is suspect No. 1 for the extinction event that wiped out the world's non-avian dinosaurs, from T-Rex to the three-horned Triceratops. A huge crater off Mexico's Yucatan Peninsula supports the asteroid hypothesis.

But most mammals, turtles, crocodiles and frogs survived, along with birds as well as most sea life, including sharks, starfish and sea urchins. With dinosaurs out of the way, mammals flourished, eventually giving rise to the species – Homo sapiens – that has sparked fear of the sixth mass extinction.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75338

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: 1 million species risk extinction due to humans – draft U.N. report

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65862

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: 1 million species risk extinction due to humans – draft U.N. report

MASS EXTINCTION EMERGENCY

Shock report about life on Earth: We’re in deep trouble

By Don Pinnock• 7 May 2019

The United Nations Special Report on Global Warming in 2018 sounded a sharp warning few could disagree with: Earth has a problem. A new UN report on Biodiversity released this week revealed the size of that problem.

In Paris at 13h30 on Monday (6 May 2019), United Nations geographer Eduardo Brondizio outlined how humans are unravelling the fabric of life on Earth. His message: If we don’t act as a species and make major changes to our lifestyle soon, our future is going to be extremely grim.

He wasn’t speculating. In his hand at its delivery was a 1,800-page assessment produced by about 500 top scientists in collaboration with representatives from 130 countries.

Brondizio, the erudite co-chair of the United Nations Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Economic Systems (IPBES), warned that natural systems are crashing worldwide, many of which are irreplaceable.

“Healthy systems are simply being overwhelmed by the deterioration happening around them.”

The report underlines our dependency on nature and our effect on it. More than 75% of food crops rely on animal pollination. Marine and land ecosystems extract 5.6 gigatons of carbon a year and without them, the planet would fry through global warming. We rely on clean air and water produced by natural processes.

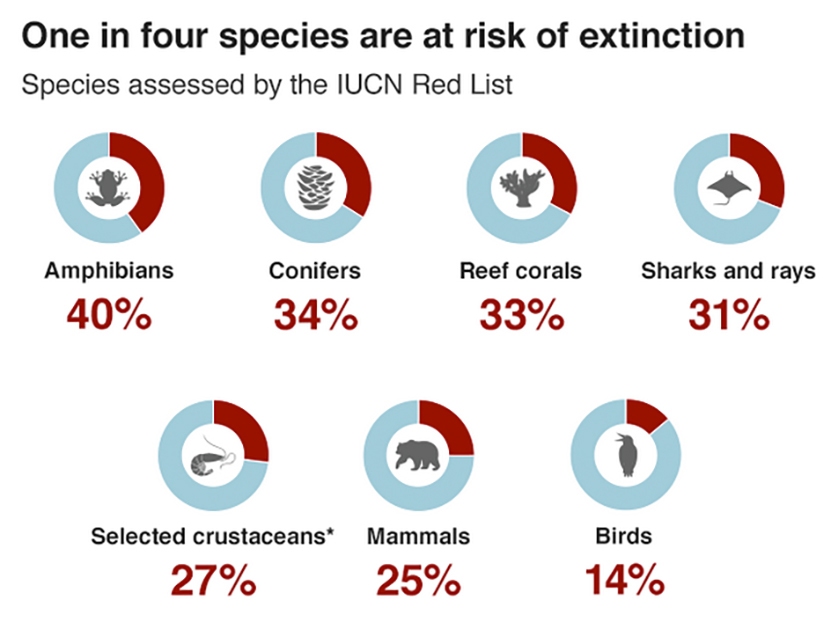

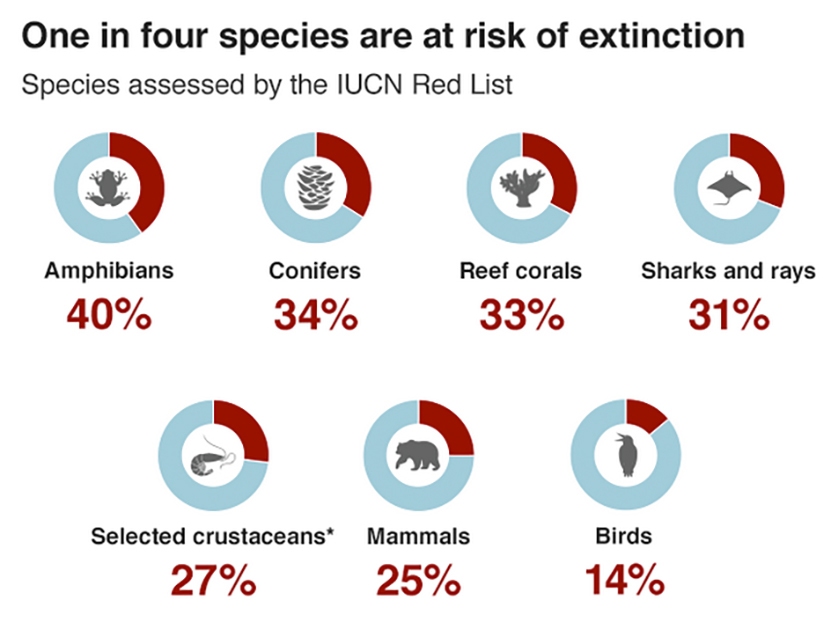

However, since 1900 the abundance of native species has declined by 20% and a further 25% are threatened, with about a million species facing extinction. Half a million of those are insects.

This impacts on all human life.

Nature is essential for achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, says the report, but current negative trends in biodiversity and ecosystems will undermine progress towards 80% of the goals’ targets related to poverty.

The report notes that the human population has doubled in the past 50 years and warns that, in future, exclusion, scarcities or unequal distributions of nature’s contributions may fuel social instability and conflict.

The way we live, says the report, is underpinned by financial systems inimical to biodiversity.

“We have to align government systems, incorporating responsibility in our economic systems in a way that reflects the full chain from production to consumption.

“We need to change our narrative, from one that associates wasteful consumption with quality of life. Economic growth is a means and not an end.”

Economic incentives have favoured expanding economic activity — and often environmental harm — over conservation or restoration. This, says the report, is supported by harmful economic incentives and wasteful farming and environmental subsidies, which it says should be discontinued. They must be replaced with policies based upon a better understanding of the multiple values of nature’s contributions.

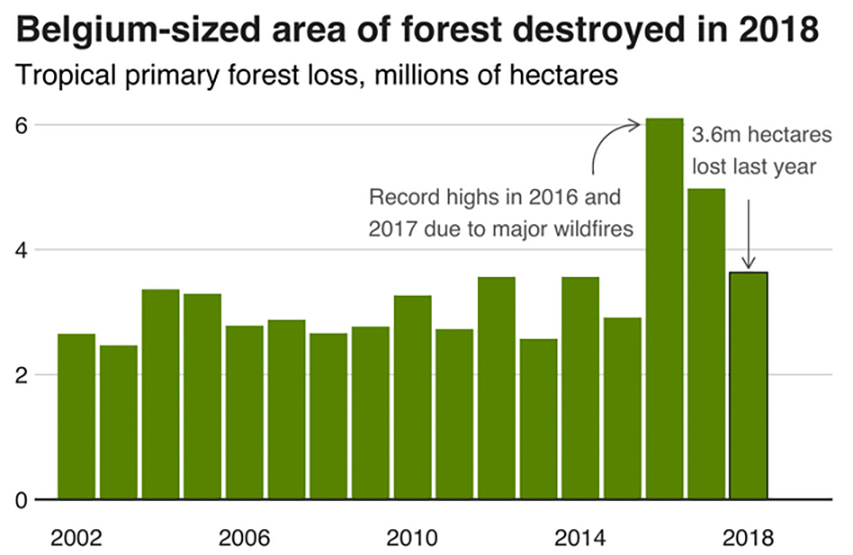

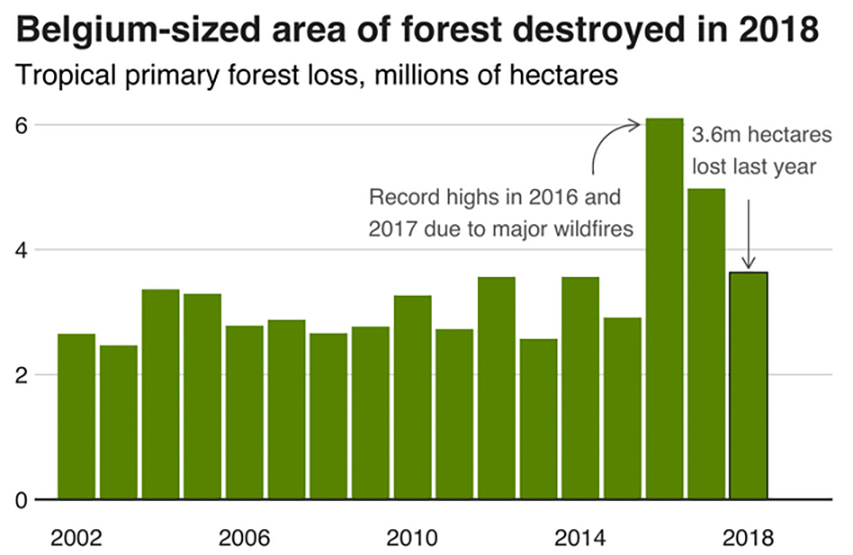

Our current extractive economic narrative has mapped itself on to the planet’s surface. Three-quarters of the Earth’s land surface was found to have been significantly altered, 66% of the ocean area is experiencing increasing cumulative impacts and more than 85% of wetland areas have been lost.

Humans, say the scientists, are also fast-forwarding biological evolution — so rapidly that effects can be seen within a few years rather than over millennia. Many of these changes are among pathogens that affect our health. The rate of this change, they say, is unprecedented in human history.

The main drivers are changes in land and sea use, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution and invasions of alien species (nearly one-fifth of the Earth’s surface is at risk of plant and animal invasions).

Crop production has increased threefold since 1970 and timber harvest by 45%, but land degradation is reducing productivity, with crops now at risk from pollinator loss, floods and hurricanes.

“Globally, local varieties and breeds of even domesticated plants and animals are disappearing,” says the report. “This loss of diversity, including genetic diversity, poses a serious risk to global food security by undermining the resilience of many agricultural systems to threats such as pests, pathogens and climate change.”

The report maps out solutions, but notes that goals for conserving nature and achieving sustainability cannot be met by current trajectories. Because of ongoing rapid declines in biodiversity, ecosystem functions and many of nature’s contributions, goals are unlikely to be met if we continue on our present course.

For this reason, it says, there is a strong possibility that ecosystem dysfunctions will continue or worsen.

What we need, says the report, are pathways that explore the effects of a low-to-moderate population growth. We need transformative changes in production and consumption of energy, food, feed, fibre and water and sustainable use. We must share the benefits of nature-friendly climate adaptation.

These, taken together, will better support the achievement of future societal and environmental objectives.

However, the report warns that transformative change will hit opposition from those with interests vested in the status quo. There are many who benefit from subsidies and damaging practices. These have to be overcome for the survival of Earth’s species, it says.

We need enhanced international co-operation linked to locally relevant measures and international co-operation.

The report lays out the steps for action as a series of levers. These involve positive incentives, building co-operation across sectors, pre-emptive action, clear decision-making in times of uncertainty and the implementation of environmental law.

Success, it says, is more likely if the focus is on visions of a good life, consumption and waste, values, inequalities, justice, communication, innovative technology, education and action.

At the briefing, former IPBES chair Sir Robert Watson added to the steps we as a species need to take.

“We have to eliminate environmental and agricultural subsidies which encourage waste, we have to incorporate natural capital, we must address vested interests that stand in the way and ditch GDP as a measure of wealth. We need to understand and incorporate natural social, human capital as measures of progress.”

If we keep doing things the way we do, warns the report, we will not achieve human wellbeing. What will things look like in 2050?

“It is our choice,” said Brondizio. “If we choose the sustainable route we will be able to feed everyone on the planet.”

Who could drive these changes, a questioner asked Brondizio from the floor. Looking up from his notes, he quipped: “Join the Peoples’ Climate Movement.”

This is the most interdisciplinary report on the Earth’s life systems ever made. No previous assessment has considered the simultaneous challenge of protecting nature, maintaining water, feeding the planet and supplying energy while mitigating climate change.

“We are seeing the possibility of tipping points and feedbacks that could lead to cascade changes in the Arctic, in the Amazon, in high mountains and the air layer,” said Brondizio.

“We are starting to see the connections — that they are symptoms of the same thing, but with no easy solutions. The patient has many symptoms, but it’s not a terminal diagnosis. However, the medicine has to start right away.”

Shock report about life on Earth: We’re in deep trouble

By Don Pinnock• 7 May 2019

The United Nations Special Report on Global Warming in 2018 sounded a sharp warning few could disagree with: Earth has a problem. A new UN report on Biodiversity released this week revealed the size of that problem.

In Paris at 13h30 on Monday (6 May 2019), United Nations geographer Eduardo Brondizio outlined how humans are unravelling the fabric of life on Earth. His message: If we don’t act as a species and make major changes to our lifestyle soon, our future is going to be extremely grim.

He wasn’t speculating. In his hand at its delivery was a 1,800-page assessment produced by about 500 top scientists in collaboration with representatives from 130 countries.

Brondizio, the erudite co-chair of the United Nations Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Economic Systems (IPBES), warned that natural systems are crashing worldwide, many of which are irreplaceable.

“Healthy systems are simply being overwhelmed by the deterioration happening around them.”

The report underlines our dependency on nature and our effect on it. More than 75% of food crops rely on animal pollination. Marine and land ecosystems extract 5.6 gigatons of carbon a year and without them, the planet would fry through global warming. We rely on clean air and water produced by natural processes.

However, since 1900 the abundance of native species has declined by 20% and a further 25% are threatened, with about a million species facing extinction. Half a million of those are insects.

This impacts on all human life.

Nature is essential for achieving the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, says the report, but current negative trends in biodiversity and ecosystems will undermine progress towards 80% of the goals’ targets related to poverty.

The report notes that the human population has doubled in the past 50 years and warns that, in future, exclusion, scarcities or unequal distributions of nature’s contributions may fuel social instability and conflict.

The way we live, says the report, is underpinned by financial systems inimical to biodiversity.

“We have to align government systems, incorporating responsibility in our economic systems in a way that reflects the full chain from production to consumption.

“We need to change our narrative, from one that associates wasteful consumption with quality of life. Economic growth is a means and not an end.”

Economic incentives have favoured expanding economic activity — and often environmental harm — over conservation or restoration. This, says the report, is supported by harmful economic incentives and wasteful farming and environmental subsidies, which it says should be discontinued. They must be replaced with policies based upon a better understanding of the multiple values of nature’s contributions.

Our current extractive economic narrative has mapped itself on to the planet’s surface. Three-quarters of the Earth’s land surface was found to have been significantly altered, 66% of the ocean area is experiencing increasing cumulative impacts and more than 85% of wetland areas have been lost.

Humans, say the scientists, are also fast-forwarding biological evolution — so rapidly that effects can be seen within a few years rather than over millennia. Many of these changes are among pathogens that affect our health. The rate of this change, they say, is unprecedented in human history.

The main drivers are changes in land and sea use, direct exploitation of organisms, climate change, pollution and invasions of alien species (nearly one-fifth of the Earth’s surface is at risk of plant and animal invasions).

Crop production has increased threefold since 1970 and timber harvest by 45%, but land degradation is reducing productivity, with crops now at risk from pollinator loss, floods and hurricanes.

“Globally, local varieties and breeds of even domesticated plants and animals are disappearing,” says the report. “This loss of diversity, including genetic diversity, poses a serious risk to global food security by undermining the resilience of many agricultural systems to threats such as pests, pathogens and climate change.”

The report maps out solutions, but notes that goals for conserving nature and achieving sustainability cannot be met by current trajectories. Because of ongoing rapid declines in biodiversity, ecosystem functions and many of nature’s contributions, goals are unlikely to be met if we continue on our present course.

For this reason, it says, there is a strong possibility that ecosystem dysfunctions will continue or worsen.

What we need, says the report, are pathways that explore the effects of a low-to-moderate population growth. We need transformative changes in production and consumption of energy, food, feed, fibre and water and sustainable use. We must share the benefits of nature-friendly climate adaptation.

These, taken together, will better support the achievement of future societal and environmental objectives.

However, the report warns that transformative change will hit opposition from those with interests vested in the status quo. There are many who benefit from subsidies and damaging practices. These have to be overcome for the survival of Earth’s species, it says.

We need enhanced international co-operation linked to locally relevant measures and international co-operation.

The report lays out the steps for action as a series of levers. These involve positive incentives, building co-operation across sectors, pre-emptive action, clear decision-making in times of uncertainty and the implementation of environmental law.

Success, it says, is more likely if the focus is on visions of a good life, consumption and waste, values, inequalities, justice, communication, innovative technology, education and action.

At the briefing, former IPBES chair Sir Robert Watson added to the steps we as a species need to take.

“We have to eliminate environmental and agricultural subsidies which encourage waste, we have to incorporate natural capital, we must address vested interests that stand in the way and ditch GDP as a measure of wealth. We need to understand and incorporate natural social, human capital as measures of progress.”

If we keep doing things the way we do, warns the report, we will not achieve human wellbeing. What will things look like in 2050?

“It is our choice,” said Brondizio. “If we choose the sustainable route we will be able to feed everyone on the planet.”

Who could drive these changes, a questioner asked Brondizio from the floor. Looking up from his notes, he quipped: “Join the Peoples’ Climate Movement.”

This is the most interdisciplinary report on the Earth’s life systems ever made. No previous assessment has considered the simultaneous challenge of protecting nature, maintaining water, feeding the planet and supplying energy while mitigating climate change.

“We are seeing the possibility of tipping points and feedbacks that could lead to cascade changes in the Arctic, in the Amazon, in high mountains and the air layer,” said Brondizio.

“We are starting to see the connections — that they are symptoms of the same thing, but with no easy solutions. The patient has many symptoms, but it’s not a terminal diagnosis. However, the medicine has to start right away.”

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65862

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

What is a ‘mass extinction’ and are we in one now?

Frédérik Saltré, Flinders University; Corey J. A. Bradshaw, Flinders University | November 12, 2019 7.03pm GMT

For more than 3.5 billion years, living organisms have thrived, multiplied and diversified to occupy every ecosystem on Earth. The flip side to this explosion of new species is that species extinctions have also always been part of the evolutionary life cycle.

But these two processes are not always in step. When the loss of species rapidly outpaces the formation of new species, this balance can be tipped enough to elicit what are known as “mass extinction” events.

A mass extinction is usually defined as a loss of about three quarters of all species in existence across the entire Earth over a “short” geological period of time. Given the vast amount of time since life first evolved on the planet, “short” is defined as anything less than 2.8 million years.

Since at least the Cambrian period that began around 540 million years ago when the diversity of life first exploded into a vast array of forms, only five extinction events have definitively met these mass-extinction criteria.

These so-called “Big Five” have become part of the scientific benchmark to determine whether human beings have today created the conditions for a sixth mass extinction.

An ammonite fossil found on the Jurassic Coast in Devon. The fossil record can help us estimate prehistoric extinction rates. Corey Bradshaw, Author provided

The Big Five

These five mass extinctions have happened on average every 100 million years or so since the Cambrian, although there is no detectable pattern in their particular timing. Each event itself lasted between 50 thousand and 2.76 million years. The first mass extinction happened at the end of the Ordovician period about 443 million years ago and wiped out over 85% of all species.

The Ordovician event seems to have been the result of two climate phenomena. First, a planetary-scale period of glaciation (a global-scale “ice age”), then a rapid warming period.

The second mass extinction occurred during the Late Devonian period around 374 million years ago. This affected around 75% of all species, most of which were bottom-dwelling invertebrates in tropical seas at that time.

This period in Earth’s past was characterised by high variation in sea levels, and rapidly alternating conditions of global cooling and warming. It was also the time when plants were starting to take over dry land, and there was a drop in global CO2 concentration; all this was accompanied by soil transformation and periods of low oxygen.

To establish a ‘mass extinction’, we first need to know what a normal rate of species loss is. from www.shutterstock.com

The third and most devastating of the Big Five occurred at the end of the Permian period around 250 million years ago. This wiped out more than 95% of all species in existence at the time.

Some of the suggested causes include an asteroid impact that filled the air with pulverised particle, creating unfavourable climate conditions for many species. These could have blocked the sun and generated intense acid rains. Some other possible causes are still debated, such as massive volcanic activity in what is today Siberia, increasing ocean toxicity caused by an increase in atmospheric CO₂, or the spread of oxygen-poor water in the deep ocean.

Fifty million years after the great Permian extinction, about 80% of the world’s species again went extinct during the Triassic event. This was possibly caused by some colossal geological activity in what is today the Atlantic Ocean that would have elevated atmospheric CO₂ concentrations, increased global temperatures, and acidified oceans.

The last and probably most well-known of the mass-extinction events happened during the Cretaceous period, when an estimated 76% of all species went extinct, including the non-avian dinosaurs. The demise of the dinosaur super predators gave mammals a new opportunity to diversify and occupy new habitats, from which human beings eventually evolved.

The most likely cause of the Cretaceous mass extinction was an extraterrestrial impact in the Yucatán of modern-day Mexico, a massive volcanic eruption in the Deccan Province of modern-day west-central India, or both in combination.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Is today’s biodiversity crisis a sixth mass extinction?

The Earth is currently experiencing an extinction crisis largely due to the exploitation of the planet by people. But whether this constitutes a sixth mass extinction depends on whether today’s extinction rate is greater than the “normal” or “background” rate that occurs between mass extinctions.

This background rate indicates how fast species would be expected to disappear in absence of human endeavour, and it’s mostly measured using the fossil record to count how many species died out between mass extinction events.

The Christmas Island Pipistrelle was announced to be extinct in 2009, years after conservationists raised concerns about its future. Lindy Lumsden

The most accepted background rate estimated from the fossil record gives an average lifespan of about one million years for a species, or one species extinction per million species-years. But this estimated rate is highly uncertain, ranging between 0.1 and 2.0 extinctions per million species-years. Whether we are now indeed in a sixth mass extinction depends to some extent on the true value of this rate. Otherwise, it’s difficult to compare Earth’s situation today with the past.

In contrast to the the Big Five, today’s species losses are driven by a mix of direct and indirect human activities, such as the destruction and fragmentation of habitats, direct exploitation like fishing and hunting, chemical pollution, invasive species, and human-caused global warming.

If we use the same approach to estimate today’s extinctions per million species-years, we come up with a rate that is between ten and 10,000 times higher than the background rate.

Even considering a conservative background rate of two extinctions per million species-years, the number of species that have gone extinct in the last century would have otherwise taken between 800 and 10,000 years to disappear if they were merely succumbing to the expected extinctions that happen at random. This alone supports the notion that the Earth is at least experiencing many more extinctions than expected from the background rate.

An endangered Indian wild dog, or Dhole. Before extinction comes a period of dwindling numbers and spread. from www.shutterstock.com

It would likely take several millions of years of normal evolutionary diversification to “restore” the Earth’s species to what they were prior to human beings rapidly changing the planet. Among land vertebrates (species with an internal skeleton), 322 species have been recorded going extinct since the year 1500, or about 1.2 species going extinction every two years.

If this doesn’t sound like much, it’s important to remember extinction is always preceded by a loss in population abundance and shrinking distributions. Based on the number of decreasing vertebrate species listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species, 32% of all known species across all ecosystems and groups are decreasing in abundance and range. In fact, the Earth has lost about 60% of all vertebrate individuals since 1970.

Australia has one of the worst recent extinction records of any continent, with more than 100 species of vertebrates going extinct since the first people arrived over 50 thousand years ago. And more than 300 animal and 1,000 plant species are now considered threatened with imminent extinction.

Read more: An end to endings: how to stop more Australian species going extinct

Although biologists are still debating how much the current extinction rate exceeds the background rate, even the most conservative estimates reveal an exceptionally rapid loss of biodiversity typical of a mass extinction event.

In fact, some studies show that the interacting conditions experienced today, such as accelerated climate change, changing atmospheric composition caused by human industry, and abnormal ecological stresses arising from human consumption of resources, define a perfect storm for extinctions. All these conditions together indicate that a sixth mass extinction is already well under way.

https://theconversation.com/what-is-a-m ... 0one%20now

For more than 3.5 billion years, living organisms have thrived, multiplied and diversified to occupy every ecosystem on Earth. The flip side to this explosion of new species is that species extinctions have also always been part of the evolutionary life cycle.

But these two processes are not always in step. When the loss of species rapidly outpaces the formation of new species, this balance can be tipped enough to elicit what are known as “mass extinction” events.

A mass extinction is usually defined as a loss of about three quarters of all species in existence across the entire Earth over a “short” geological period of time. Given the vast amount of time since life first evolved on the planet, “short” is defined as anything less than 2.8 million years.

Since at least the Cambrian period that began around 540 million years ago when the diversity of life first exploded into a vast array of forms, only five extinction events have definitively met these mass-extinction criteria.

These so-called “Big Five” have become part of the scientific benchmark to determine whether human beings have today created the conditions for a sixth mass extinction.

An ammonite fossil found on the Jurassic Coast in Devon. The fossil record can help us estimate prehistoric extinction rates. Corey Bradshaw, Author provided

The Big Five

These five mass extinctions have happened on average every 100 million years or so since the Cambrian, although there is no detectable pattern in their particular timing. Each event itself lasted between 50 thousand and 2.76 million years. The first mass extinction happened at the end of the Ordovician period about 443 million years ago and wiped out over 85% of all species.

The Ordovician event seems to have been the result of two climate phenomena. First, a planetary-scale period of glaciation (a global-scale “ice age”), then a rapid warming period.

The second mass extinction occurred during the Late Devonian period around 374 million years ago. This affected around 75% of all species, most of which were bottom-dwelling invertebrates in tropical seas at that time.

This period in Earth’s past was characterised by high variation in sea levels, and rapidly alternating conditions of global cooling and warming. It was also the time when plants were starting to take over dry land, and there was a drop in global CO2 concentration; all this was accompanied by soil transformation and periods of low oxygen.

To establish a ‘mass extinction’, we first need to know what a normal rate of species loss is. from www.shutterstock.com

The third and most devastating of the Big Five occurred at the end of the Permian period around 250 million years ago. This wiped out more than 95% of all species in existence at the time.

Some of the suggested causes include an asteroid impact that filled the air with pulverised particle, creating unfavourable climate conditions for many species. These could have blocked the sun and generated intense acid rains. Some other possible causes are still debated, such as massive volcanic activity in what is today Siberia, increasing ocean toxicity caused by an increase in atmospheric CO₂, or the spread of oxygen-poor water in the deep ocean.

Fifty million years after the great Permian extinction, about 80% of the world’s species again went extinct during the Triassic event. This was possibly caused by some colossal geological activity in what is today the Atlantic Ocean that would have elevated atmospheric CO₂ concentrations, increased global temperatures, and acidified oceans.

The last and probably most well-known of the mass-extinction events happened during the Cretaceous period, when an estimated 76% of all species went extinct, including the non-avian dinosaurs. The demise of the dinosaur super predators gave mammals a new opportunity to diversify and occupy new habitats, from which human beings eventually evolved.

The most likely cause of the Cretaceous mass extinction was an extraterrestrial impact in the Yucatán of modern-day Mexico, a massive volcanic eruption in the Deccan Province of modern-day west-central India, or both in combination.

The Conversation, CC BY-ND

Is today’s biodiversity crisis a sixth mass extinction?

The Earth is currently experiencing an extinction crisis largely due to the exploitation of the planet by people. But whether this constitutes a sixth mass extinction depends on whether today’s extinction rate is greater than the “normal” or “background” rate that occurs between mass extinctions.

This background rate indicates how fast species would be expected to disappear in absence of human endeavour, and it’s mostly measured using the fossil record to count how many species died out between mass extinction events.

The Christmas Island Pipistrelle was announced to be extinct in 2009, years after conservationists raised concerns about its future. Lindy Lumsden

The most accepted background rate estimated from the fossil record gives an average lifespan of about one million years for a species, or one species extinction per million species-years. But this estimated rate is highly uncertain, ranging between 0.1 and 2.0 extinctions per million species-years. Whether we are now indeed in a sixth mass extinction depends to some extent on the true value of this rate. Otherwise, it’s difficult to compare Earth’s situation today with the past.

In contrast to the the Big Five, today’s species losses are driven by a mix of direct and indirect human activities, such as the destruction and fragmentation of habitats, direct exploitation like fishing and hunting, chemical pollution, invasive species, and human-caused global warming.

If we use the same approach to estimate today’s extinctions per million species-years, we come up with a rate that is between ten and 10,000 times higher than the background rate.

Even considering a conservative background rate of two extinctions per million species-years, the number of species that have gone extinct in the last century would have otherwise taken between 800 and 10,000 years to disappear if they were merely succumbing to the expected extinctions that happen at random. This alone supports the notion that the Earth is at least experiencing many more extinctions than expected from the background rate.

An endangered Indian wild dog, or Dhole. Before extinction comes a period of dwindling numbers and spread. from www.shutterstock.com

It would likely take several millions of years of normal evolutionary diversification to “restore” the Earth’s species to what they were prior to human beings rapidly changing the planet. Among land vertebrates (species with an internal skeleton), 322 species have been recorded going extinct since the year 1500, or about 1.2 species going extinction every two years.

If this doesn’t sound like much, it’s important to remember extinction is always preceded by a loss in population abundance and shrinking distributions. Based on the number of decreasing vertebrate species listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species, 32% of all known species across all ecosystems and groups are decreasing in abundance and range. In fact, the Earth has lost about 60% of all vertebrate individuals since 1970.

Australia has one of the worst recent extinction records of any continent, with more than 100 species of vertebrates going extinct since the first people arrived over 50 thousand years ago. And more than 300 animal and 1,000 plant species are now considered threatened with imminent extinction.

Read more: An end to endings: how to stop more Australian species going extinct

Although biologists are still debating how much the current extinction rate exceeds the background rate, even the most conservative estimates reveal an exceptionally rapid loss of biodiversity typical of a mass extinction event.

In fact, some studies show that the interacting conditions experienced today, such as accelerated climate change, changing atmospheric composition caused by human industry, and abnormal ecological stresses arising from human consumption of resources, define a perfect storm for extinctions. All these conditions together indicate that a sixth mass extinction is already well under way.

https://theconversation.com/what-is-a-m ... 0one%20now

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65862

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: What is a ‘mass extinction’ and are we in one now?

Why you should care about the current wave of mass extinctions

Commentary by Gianluca Serra on 25 November 2019

- The extinction crisis we are witnessing is only the beginning of a wave of mass ecocide of non-human life on Earth, a process that could wipe out a million species of plants and ani-mals from our planet in the short term (read: decades). About 15 thousand scientific studies (!) support this terrifying conclusion, as it can be read in the assessment report produced by the independent UN Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

- Certainly this is not what I dreamed of as a child in love with nature and wildlife. But how could I have ever imagined back then, in the 1970s, that during my first 50 years of life the global human population would literally double? That the global economy would increase four-fold, and that in parallel — and not by coincidence — wildlife populations would drop by a staggering 60 percent globally? How could I have ever imagined back then that I would personally witness and document, as a field conservationist, actual extinctions on the ground?

- In order to create a critical mass of awareness globally, there is still an important question to answer: Why should we care to conserve what is left of wild ecosystems and species of our planet? This is a question we should be ready to answer clearly, especially considering that most of the world population currently lives in urban centers, remains quite unaware of eco-logical matters, and is disconnected from nature — and therefore can’t fully appreciate how much our survival as a species is still deeply dependent on ecosystems and nature.

- This post is a commentary. The views expressed are those of the author, not necessarily Mongabay.

The scientific imprimatur fell on us just six months ago: Yes, the extinction crisis we are witnessing is only the beginning of a wave of mass ecocide of non-human life on Earth, a process that could wipe out a million species of plants and animals from our planet in the short term (read: decades).

About 15 thousand scientific studies (!) support this terrifying conclusion, as it can be read in the assessment report produced by the independent UN Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

As it turns out, us environmental activists were not so much “catastrophists” during the past decades, in campaigning to protect nature and ringing alarms now and then about the plight of single wildlife species, as we were realists.

Gloom and doom

Certainly this is not what I dreamed of as a child in love with nature and wildlife. But how could I have ever imagined back then, in the 1970s, that during my first 50 years of life the global human population would literally double? That the global economy would increase four-fold, and that in parallel — and not by coincidence — wildlife populations would drop by a staggering 60 percent globally? How could I have ever imagined back then that I would personally witness and document, as a field conservationist, actual extinctions on the ground?

Now we have scientific “certification” of the extinction crisis, implicitly admitting that the Convention on Biodiversity, signed by most countries of the world following the UN Rio Summit in 1992, has failed. It was the classic “too little, too late” scenario. For years, us ecologists and activists have maintained (and feared) that we won’t achieve much under the current consumeristic, ecologically unsustainable socio-economic system — and the IPBES report now confirms this viewpoint.

Needless to say, for a naturalist and wildlife lover like me, this is not the best historic period to have been born in. Still, I am fully aware that I have had the chance to study and focus on my passions and interests precisely because of the socio-economic development that followed the second world war. In fact, no serious and pragmatic environmentalist would argue that socio-economic progress is unnecessary: instead, we have been saying for decades that a new socio-economic paradigm is needed based on ecological and ethical sustainability rather than on magic assumptions like the infinite economic growth and a radical laissez faire approach, derived from the dominant free market ideology.

A shift of socio-economic paradigm is nowadays increasingly supported and acknowledged by authoritative economists.

Tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) photographed in 2013 in Niue island, Polynesia. Shark populations have dramatically declined during the past 2 decades — in certain areas up to 90% — due to unsustainable harvest linked to the trade of the shark fin. Image courtesy of Isabella Chowra.

Historical process

There is some relief in exercising historical and biological relativism and by reflecting on the grand scheme of things. What we are witnessing today is just the final stage of a process that began about 70 thousand years ago, when some unknown change in the neural wiring of human brains unleashed the so-called “cognitive revolution.”

Since then, what used to be a quite low-profile species, ranking in the mid to lower levels of the food chain, gradually advanced to become a feared top predator, able to kill prey much larger than its size. Thanks to its unmatched communication and organizational skills, Homo sapiens set out to colonize and invade the entire planet, causing the annihilation of other species — often on such a grand scale that it became the #1 Ecological Serial Killer of the Planet.

As early as 45 thousand years ago, the sapiens landed in Australia, causing an ecological disaster that wiped out most larger marsupial predators. Similar fates befell the megafauna of North America (ca. 16,000 years ago), of Madagascar, and of New Zealand (only a few hundred years ago in both the latter two cases).

Not to mention that, in parallel with the advance of the sapiens, all other species of humans (i.e. those, like us, belonging to the genus Homo, i.e. our closest kinship) also vanished. Only a coincidence? (Probably not, we have most likely even caused human species annihilations…)

With the advent of agriculture and monotheistic religions some 10 thousand years ago, the anthropocentric view of the planet was sacralized and institutionalized: since then we have convinced ourselves that we are not part of nature anymore, we are of a superior level; and that animals and plants were created for our own use and consumption.

Three human-induced ecocide waves

During the last two hundred years, a sudden acceleration in the rate of nature consumption by the sapiens took place following the scientific and industrial revolutions, the imperialism of European nations, and the simultaneous advent of capitalism. The booming of the human population and of the global economic market in the past five decades have delivered the last blow to the planet’s ecosystems and wildlife.

So, in brief, there have been three pulses of ecocides directly caused by the sapiens’ inexorable expansion: the first provoked by hunter-gatherers during the epic process of colonizing the entire planet on foot and through sea vessels; the second prompted by agriculture; and the third being the current one we are living through right now.

As a result, while 10 thousand years ago wildlife was 99 percent of the whole planet’s land vertebrate biomass, today it is only 1 percent; the rest being humans and their “commodity” domestic animals.

Visualization of the massive shift in biomass proportions — humans and their domestic animals versus wildlife — that has taken place during the past 10,000 years on planet Earth. Chart courtesy of populationmatters.org.

We should actually be thrilled to be part of and witnesses to another historical turn in Homo sapiens’ “evolution.” The problem is that we are now under a UN ultimatum: Just last year, top scientists informed us that we are left with another 12 years if we are to avoid a climate catastrophe on the planet. So, following the threat to human survival posed by the prospect of global nuclear war just a few decades ago, we are again under another dire threat of self-immolation.

A much needed change

If there is one important lesson I’ve learned in my experience on the front lines of nature devastation, it’s that individual virtuosity — or single virtuous projects — won’t make any difference or have any impact globally under the current dominant system. Yet, for decades, an emphasis on individual virtuosity (use the bike instead of the car, collect garbage at the beach, turn off the lights when not needed, etc.) has been the main leit motif for environmental engagement.

On the contrary, “transformative changes” are needed to tackle the current global ecological challenge, a term very appropriately used in the IPBES report. Given the fact that, until now, governments and international organizations (tightly “supervised” by the oil-dependent economic and financial élite of the world) have not shown any willingness to enact such transformative changes, the only hope left is a mass global grassroots movement pushing governments for the bold reforms required — before it really is too late.

What is needed is a high-level political global reform — a “green new deal” — with a focus on both limiting consumption of resources and curbing the global population’s exponential growth. Focusing on only one of these two issues won’t save us. (Yes, industrialized countries still fantasize that the latter is the main issue to be tackled, removing from their conscience the former one).

Greta Thunberg and the current global movement of students pursuing the climate strikes are a ray of hope, as is the Extinction Rebellion movement. I can barely believe my eyes: the “new generations” we have mentioned so many times in the past decades have grown up and taken to the streets with their own legs and brains! Here there is hope — but they need support.

Diversity of wild fruits from the rainforest of Samoa, Polynesia. Image courtesy of Gianluca Serra.

A key question

In order to create a critical mass of awareness globally, there is still an important question to answer: Why should we care to conserve what is left of wild ecosystems and species of our planet?

This is a question we should be ready to answer clearly, especially considering that most of the world population currently lives in urban centers, remains quite unaware of ecological matters, and is disconnected from nature — and therefore can’t fully appreciate how much our survival as a species is still deeply dependent on ecosystems and nature.

There has been a debate recently sparked by a quite provocative article authored by biologist Alexander Pyron, who basically says that we should not bother to conserve ecosystems and species unless we “directly” need them.

One of the key lessons of ecology and life sciences is that everything is interconnected on the planet in ways we are barely aware of. How can we establish that we do not need a given ecosystem or a species? Especially considering that our knowledge on these subjects is still so sketchy in terms of ecological processes, ecosystems, and species. Do you reckon Dr. Pyron would accept to fly on an aircraft from which a few “unimportant” rivets have been removed by the company to save money, just before taking off?

The answer

We should care about nature and wildlife simply because we are still part of it and because we still need functional ecosystems around us to provide basic life needs like clean air, water and soil; and to get nutrients of all sorts, as well as food and scientific knowledge (we tend to forget that most drugs routinely used in modern medicine were discovered thanks to studying the secrets of nature).

Surviving primary rainforest from Upolu island, Samoa, Polynesia. Image courtesy of Gianluca Serra.

Not to mention that the importance of having healthy nature and wild lands around us has deep spiritual, aesthetic, and psychological implications for our well being that we are just beginning to understand (see conservation psychology).

Perhaps more importantly, we should be deeply empathetic about the future of the Greta Thunbergs of the world – our children and grandchildren. As a commonsense measure of precaution, we should leave them a living planet that is still ecologically functional and alive. This seems like a basic ethical call.

Let’s not get enchanted and daydream again about the myths and shallow promises of high-tech utopians always claiming to be able to fix everything. The truth is that we don’t yet fully understand and we are therefore not able to tackle complex phenomenons related to life-supporting systems of the planet; the approach of high-tech utopians in these fields is still so naive and clumsily reductionist.

The economy is important, no doubt: we need it for our survival and well being. But its formulation and implementation during the past two centuries has driven us into a dangerous no-return, life-threatening development path.

Just common sense

In other words, the economy, in order to be sustainable and viable for the whole of humanity nowadays, should be based on the most elementary principles on which life is based on Earth. These are basic rules of common sense. Even a tree or a sea urchin may have a sense that planet Earth will not be able to support 10 billion bipeds, each of them with the American dream imprinted in her/his head.

Infinite economic growth is a magic buzz invented by once-euphoric positivist economists and capitalists. Within the span of a century or so it has turned into an archaic and dangerous notion. It’s time to wake up for a serious life reality check.

After all, there is no infinite anything in the whole galaxy!

Green turtle (Chelonia mydas) on the reef of Fiji in 2013. Nearly all turtles species are classified as endangered and threatened with extinction. Image courtesy of Isabella Chowra.

Gianluca Serra (PhD) has been engaged in frontline wildlife conservation as a civil servant and practitioner during the past two decades internationally, on four continents. A photographic booklet about a 10-year conservation saga in the Syrian desert is freely downloadable at thelastflight.org. A non-fiction narrative book, in the form of a literary reportage, about the same subject was published in Italy in 2016 (Salam è tornata/Exorma); an unpublished English version is also available.

CORRECTION: This piece originally stated that, 10 thousand years ago, wildlife was 99 percent of the whole planet’s biomass and today it is just 1 percent, with the rest being humans, domestic animals, and plants. The piece has been edited to reflect that wildlife was 99 percent of land vertebrate biomass 10 thousand years ago but 1 percent today, and the rest is humans and domestic animals, with these figures not including plants. Mongabay regrets the error.

Commentary by Gianluca Serra on 25 November 2019

- The extinction crisis we are witnessing is only the beginning of a wave of mass ecocide of non-human life on Earth, a process that could wipe out a million species of plants and ani-mals from our planet in the short term (read: decades). About 15 thousand scientific studies (!) support this terrifying conclusion, as it can be read in the assessment report produced by the independent UN Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

- Certainly this is not what I dreamed of as a child in love with nature and wildlife. But how could I have ever imagined back then, in the 1970s, that during my first 50 years of life the global human population would literally double? That the global economy would increase four-fold, and that in parallel — and not by coincidence — wildlife populations would drop by a staggering 60 percent globally? How could I have ever imagined back then that I would personally witness and document, as a field conservationist, actual extinctions on the ground?

- In order to create a critical mass of awareness globally, there is still an important question to answer: Why should we care to conserve what is left of wild ecosystems and species of our planet? This is a question we should be ready to answer clearly, especially considering that most of the world population currently lives in urban centers, remains quite unaware of eco-logical matters, and is disconnected from nature — and therefore can’t fully appreciate how much our survival as a species is still deeply dependent on ecosystems and nature.

- This post is a commentary. The views expressed are those of the author, not necessarily Mongabay.

The scientific imprimatur fell on us just six months ago: Yes, the extinction crisis we are witnessing is only the beginning of a wave of mass ecocide of non-human life on Earth, a process that could wipe out a million species of plants and animals from our planet in the short term (read: decades).

About 15 thousand scientific studies (!) support this terrifying conclusion, as it can be read in the assessment report produced by the independent UN Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

As it turns out, us environmental activists were not so much “catastrophists” during the past decades, in campaigning to protect nature and ringing alarms now and then about the plight of single wildlife species, as we were realists.

Gloom and doom

Certainly this is not what I dreamed of as a child in love with nature and wildlife. But how could I have ever imagined back then, in the 1970s, that during my first 50 years of life the global human population would literally double? That the global economy would increase four-fold, and that in parallel — and not by coincidence — wildlife populations would drop by a staggering 60 percent globally? How could I have ever imagined back then that I would personally witness and document, as a field conservationist, actual extinctions on the ground?

Now we have scientific “certification” of the extinction crisis, implicitly admitting that the Convention on Biodiversity, signed by most countries of the world following the UN Rio Summit in 1992, has failed. It was the classic “too little, too late” scenario. For years, us ecologists and activists have maintained (and feared) that we won’t achieve much under the current consumeristic, ecologically unsustainable socio-economic system — and the IPBES report now confirms this viewpoint.

Needless to say, for a naturalist and wildlife lover like me, this is not the best historic period to have been born in. Still, I am fully aware that I have had the chance to study and focus on my passions and interests precisely because of the socio-economic development that followed the second world war. In fact, no serious and pragmatic environmentalist would argue that socio-economic progress is unnecessary: instead, we have been saying for decades that a new socio-economic paradigm is needed based on ecological and ethical sustainability rather than on magic assumptions like the infinite economic growth and a radical laissez faire approach, derived from the dominant free market ideology.

A shift of socio-economic paradigm is nowadays increasingly supported and acknowledged by authoritative economists.

Tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) photographed in 2013 in Niue island, Polynesia. Shark populations have dramatically declined during the past 2 decades — in certain areas up to 90% — due to unsustainable harvest linked to the trade of the shark fin. Image courtesy of Isabella Chowra.

Historical process

There is some relief in exercising historical and biological relativism and by reflecting on the grand scheme of things. What we are witnessing today is just the final stage of a process that began about 70 thousand years ago, when some unknown change in the neural wiring of human brains unleashed the so-called “cognitive revolution.”

Since then, what used to be a quite low-profile species, ranking in the mid to lower levels of the food chain, gradually advanced to become a feared top predator, able to kill prey much larger than its size. Thanks to its unmatched communication and organizational skills, Homo sapiens set out to colonize and invade the entire planet, causing the annihilation of other species — often on such a grand scale that it became the #1 Ecological Serial Killer of the Planet.

As early as 45 thousand years ago, the sapiens landed in Australia, causing an ecological disaster that wiped out most larger marsupial predators. Similar fates befell the megafauna of North America (ca. 16,000 years ago), of Madagascar, and of New Zealand (only a few hundred years ago in both the latter two cases).

Not to mention that, in parallel with the advance of the sapiens, all other species of humans (i.e. those, like us, belonging to the genus Homo, i.e. our closest kinship) also vanished. Only a coincidence? (Probably not, we have most likely even caused human species annihilations…)

With the advent of agriculture and monotheistic religions some 10 thousand years ago, the anthropocentric view of the planet was sacralized and institutionalized: since then we have convinced ourselves that we are not part of nature anymore, we are of a superior level; and that animals and plants were created for our own use and consumption.

Three human-induced ecocide waves

During the last two hundred years, a sudden acceleration in the rate of nature consumption by the sapiens took place following the scientific and industrial revolutions, the imperialism of European nations, and the simultaneous advent of capitalism. The booming of the human population and of the global economic market in the past five decades have delivered the last blow to the planet’s ecosystems and wildlife.

So, in brief, there have been three pulses of ecocides directly caused by the sapiens’ inexorable expansion: the first provoked by hunter-gatherers during the epic process of colonizing the entire planet on foot and through sea vessels; the second prompted by agriculture; and the third being the current one we are living through right now.

As a result, while 10 thousand years ago wildlife was 99 percent of the whole planet’s land vertebrate biomass, today it is only 1 percent; the rest being humans and their “commodity” domestic animals.

Visualization of the massive shift in biomass proportions — humans and their domestic animals versus wildlife — that has taken place during the past 10,000 years on planet Earth. Chart courtesy of populationmatters.org.

We should actually be thrilled to be part of and witnesses to another historical turn in Homo sapiens’ “evolution.” The problem is that we are now under a UN ultimatum: Just last year, top scientists informed us that we are left with another 12 years if we are to avoid a climate catastrophe on the planet. So, following the threat to human survival posed by the prospect of global nuclear war just a few decades ago, we are again under another dire threat of self-immolation.

A much needed change

If there is one important lesson I’ve learned in my experience on the front lines of nature devastation, it’s that individual virtuosity — or single virtuous projects — won’t make any difference or have any impact globally under the current dominant system. Yet, for decades, an emphasis on individual virtuosity (use the bike instead of the car, collect garbage at the beach, turn off the lights when not needed, etc.) has been the main leit motif for environmental engagement.

On the contrary, “transformative changes” are needed to tackle the current global ecological challenge, a term very appropriately used in the IPBES report. Given the fact that, until now, governments and international organizations (tightly “supervised” by the oil-dependent economic and financial élite of the world) have not shown any willingness to enact such transformative changes, the only hope left is a mass global grassroots movement pushing governments for the bold reforms required — before it really is too late.

What is needed is a high-level political global reform — a “green new deal” — with a focus on both limiting consumption of resources and curbing the global population’s exponential growth. Focusing on only one of these two issues won’t save us. (Yes, industrialized countries still fantasize that the latter is the main issue to be tackled, removing from their conscience the former one).

Greta Thunberg and the current global movement of students pursuing the climate strikes are a ray of hope, as is the Extinction Rebellion movement. I can barely believe my eyes: the “new generations” we have mentioned so many times in the past decades have grown up and taken to the streets with their own legs and brains! Here there is hope — but they need support.

Diversity of wild fruits from the rainforest of Samoa, Polynesia. Image courtesy of Gianluca Serra.

A key question

In order to create a critical mass of awareness globally, there is still an important question to answer: Why should we care to conserve what is left of wild ecosystems and species of our planet?

This is a question we should be ready to answer clearly, especially considering that most of the world population currently lives in urban centers, remains quite unaware of ecological matters, and is disconnected from nature — and therefore can’t fully appreciate how much our survival as a species is still deeply dependent on ecosystems and nature.

There has been a debate recently sparked by a quite provocative article authored by biologist Alexander Pyron, who basically says that we should not bother to conserve ecosystems and species unless we “directly” need them.

One of the key lessons of ecology and life sciences is that everything is interconnected on the planet in ways we are barely aware of. How can we establish that we do not need a given ecosystem or a species? Especially considering that our knowledge on these subjects is still so sketchy in terms of ecological processes, ecosystems, and species. Do you reckon Dr. Pyron would accept to fly on an aircraft from which a few “unimportant” rivets have been removed by the company to save money, just before taking off?

The answer

We should care about nature and wildlife simply because we are still part of it and because we still need functional ecosystems around us to provide basic life needs like clean air, water and soil; and to get nutrients of all sorts, as well as food and scientific knowledge (we tend to forget that most drugs routinely used in modern medicine were discovered thanks to studying the secrets of nature).

Surviving primary rainforest from Upolu island, Samoa, Polynesia. Image courtesy of Gianluca Serra.

Not to mention that the importance of having healthy nature and wild lands around us has deep spiritual, aesthetic, and psychological implications for our well being that we are just beginning to understand (see conservation psychology).

Perhaps more importantly, we should be deeply empathetic about the future of the Greta Thunbergs of the world – our children and grandchildren. As a commonsense measure of precaution, we should leave them a living planet that is still ecologically functional and alive. This seems like a basic ethical call.

Let’s not get enchanted and daydream again about the myths and shallow promises of high-tech utopians always claiming to be able to fix everything. The truth is that we don’t yet fully understand and we are therefore not able to tackle complex phenomenons related to life-supporting systems of the planet; the approach of high-tech utopians in these fields is still so naive and clumsily reductionist.

The economy is important, no doubt: we need it for our survival and well being. But its formulation and implementation during the past two centuries has driven us into a dangerous no-return, life-threatening development path.

Just common sense

In other words, the economy, in order to be sustainable and viable for the whole of humanity nowadays, should be based on the most elementary principles on which life is based on Earth. These are basic rules of common sense. Even a tree or a sea urchin may have a sense that planet Earth will not be able to support 10 billion bipeds, each of them with the American dream imprinted in her/his head.

Infinite economic growth is a magic buzz invented by once-euphoric positivist economists and capitalists. Within the span of a century or so it has turned into an archaic and dangerous notion. It’s time to wake up for a serious life reality check.

After all, there is no infinite anything in the whole galaxy!

Green turtle (Chelonia mydas) on the reef of Fiji in 2013. Nearly all turtles species are classified as endangered and threatened with extinction. Image courtesy of Isabella Chowra.

Gianluca Serra (PhD) has been engaged in frontline wildlife conservation as a civil servant and practitioner during the past two decades internationally, on four continents. A photographic booklet about a 10-year conservation saga in the Syrian desert is freely downloadable at thelastflight.org. A non-fiction narrative book, in the form of a literary reportage, about the same subject was published in Italy in 2016 (Salam è tornata/Exorma); an unpublished English version is also available.

CORRECTION: This piece originally stated that, 10 thousand years ago, wildlife was 99 percent of the whole planet’s biomass and today it is just 1 percent, with the rest being humans, domestic animals, and plants. The piece has been edited to reflect that wildlife was 99 percent of land vertebrate biomass 10 thousand years ago but 1 percent today, and the rest is humans and domestic animals, with these figures not including plants. Mongabay regrets the error.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65862

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: What is a ‘mass extinction’ and are we in one now?

Bird species are facing extinction hundreds of times faster than previously thought

January 16, 2020 3.41pm SAST Updated January 18, 2020 11.24pm - Arne Mooers | Professor, Biodiversity, Phylogeny & Evolution, Simon Fraser University

Extinction, or the disappearance of an entire species, is commonplace. Species have been forming, persisting and then shuffling off their mortal coil since life began on Earth. However, evidence suggests the number of species going extinct, and the rate at which they disappear, is increasing dramatically.

Our recent work suggests that the rate at which species are going extinct may be many times higher than previously estimated — at least for birds. The good news, however, is that recent conservation efforts have slowed this rate a lot.

Old rates