Re: In SA, Mining companies don't follow the rules

Posted: Thu Jun 09, 2022 11:54 am

ACID MINE DRAINAGE

6,000 health and environmental ‘time bombs’ still to be defused – Govt decades behind schedule

A pile of poisoned fish dumped next to Loskop Dam after an acid mine leak at the abandoned Kromdraai coal mine. (Photo: Supplied)

By Tony Carnie | 08 Jun 2022

So little money has been allocated to cleaning up the legacy of the South African mining industry that it will take another 70 years to clean up just a fraction of the country’s more than 6,000 abandoned mines.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

There are roughly 6,100 “derelict or ownerless” mines scattered across South Africa, many of which can expose people and the environment to significant harm due to pollution of the air, water and soil.

Whether it is the tiny, needle-like asbestos fibres that slice up the delicate tissue inside human lungs; the acidic mine water that melts the organs of fish or the radioactive mining waste that can turn land and water into permanent “dead zones”, widespread pollution from more than a century of mining has saddled South African taxpayers with a hefty clean-up bill.

Yet the government is nowhere close to meeting its mine rehabilitation targets, according to a recent report by the Auditor-General that exposes 16 years of abject failure by Minister Gwede Mantashe’s Department of Mineral Resources and Energy.

For example, the department is only rehabilitating an average of three asbestos mines each year.

“At this rate, it will take approximately 69 years to rehabilitate the remaining 229 derelict and ownerless asbestos mines,” says the report

Auditor-General Tsakani Maluleke noted that the rehabilitation price tag for abandoned asbestos mines alone had been estimated at R3,860,741,741 (R3.8-billion) – and this figure excludes the clean-up and sealing costs for most of the other high-risk abandoned mines.

The brick and concrete ‘plug’ that was torn away by the pressure of acid mine water at the old Kromdraai mine in Mpumalanga. (Photo: Thungela Resources)

One example of how mines can literally “explode” came to light just a few months ago when large volumes of highly acidic water burst to the surface of the old Kromdraai coal mine near Emalahleni, Mpumalanga.

Sulphur-rich minerals are relatively harmless when left undisturbed below the Earth’s surface. But when exposed to water and air during mining, natural chemical reactions can produce sulphuric acid.

Unless this contaminated water is removed and treated, it flows up to the surface and escapes onto the land and surrounding rivers.

Dead fish

At Kromdraai, the pressure from acidic mine water tore apart a brick and concrete seal and left a trail of destruction that stretched nearly 60km along the Kromdraaispruit, Saalboomspruit, Wilge and Olifants rivers, before it was finally diluted in the upper reaches of the Loskop Dam.

At least three tonnes of dead fish were scooped up in the aftermath and it may take decades to restock these rivers and enable fish and less visible aquatic life forms to recover.

Closer to Johannesburg, acid mine drainage and dissolved uranium have created a radioactive environment that cannot support any life forms around the Robinson Dam on the West Rand.

The Auditor-General’s report also noted that South Africa has the highest rate of mesothelioma in the world. This is an aggressive form of lung cancer caused by airborne asbestos fibres.

Estimates showed that nearly 1.6 million people in South Africa live near, or next to mine waste dumps, exposing communities to windblown dust fallout that can lead to respiratory infection, heart disease and lung disease.

“People who live in post-mining environments with either partially rehabilitated or unrehabilitated asbestos waste dumps continue to be at risk of contracting asbestos-related diseases. There is no ‘safe’ level of asbestos exposure,” the report states.

This is one of the reasons why the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy had prioritised old asbestos mines and other high-risk mining operations for rehabilitation.

The Auditor-General notes that from 1991, the Minerals Act required mining rights holders to manage environmental impacts and rehabilitate the land surface.

The 2002 Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act tightened up the law by requiring rights holders to fully rehabilitate mines before the department would issue a closure certificate.

This act also mandated the department to manage those mines that had been abandoned before 2002, (now known as derelict and ownerless mines).

The Auditor-General conducted an initial audit of the department’s mine rehabilitation programme in 2009, followed by a second audit in 2021.

“Although we recognise that the department has made some progress since the previous audit, there are still many critical areas that affect economical, efficient and effective rehabilitation and that need to be improved.

“Our audit revealed that the rehabilitation programme achieved only minor improvements over the past 12 years… with the average number of mines rehabilitated in a year increasing from 1.67 mines in 2009 to 2.25 mines in 2021.”

The Auditor-General also found that, despite the clear risks to several communities, the National Department of Health did not keep health-related statistics on the impact of unrehabilitated D&O (derelict and ownerless) mines.

Mantashe’s department had set a 2021 target date to rehabilitate about 2,000 large-scale mines considered to pose the greatest risks to society and the environment. The other 6,100 D&O mines were targeted for rehabilitation by 2038.

In stark contrast to these targets, however, none of the 2,322 “high-risk” mines was rehabilitated (apart from a handful of asbestos mines).

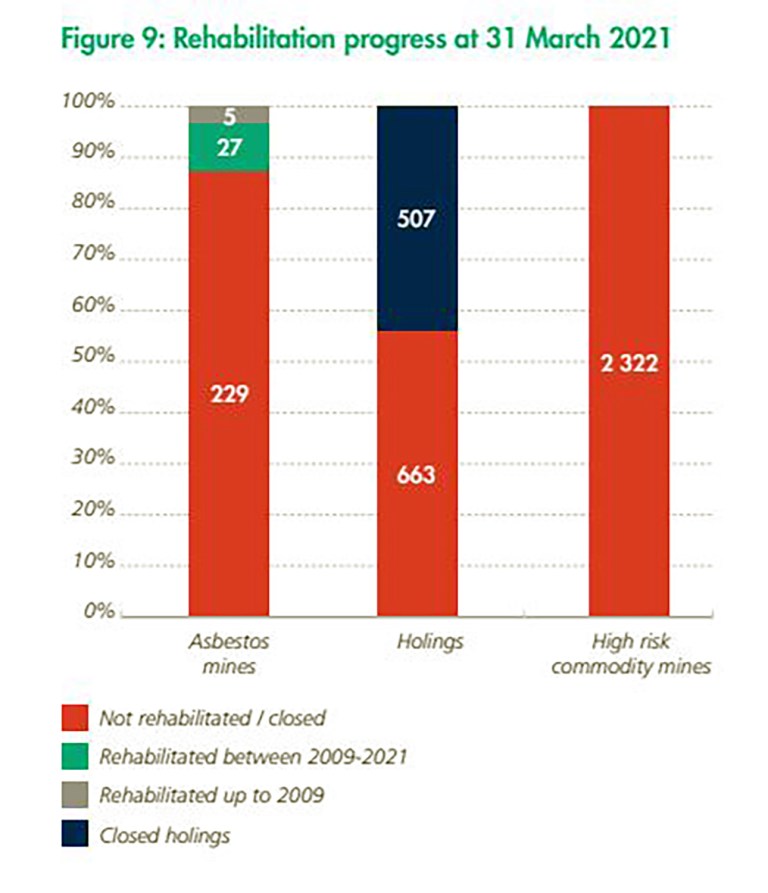

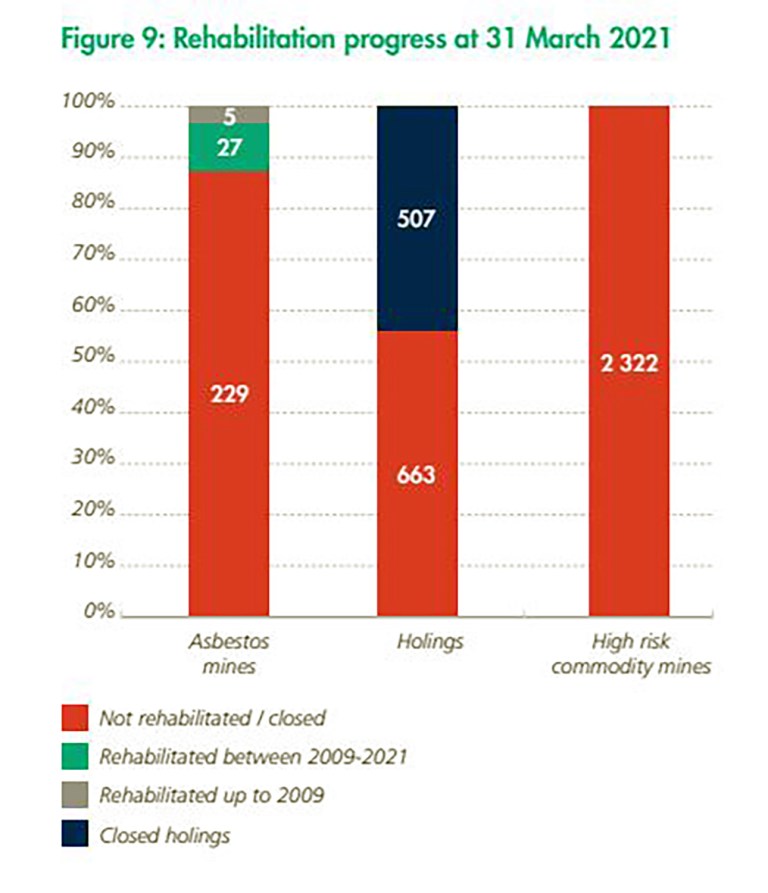

A graph showing the dismal progress in rehabilitating abandoned high-risk mines in South Africa. The red bar shows the number of mines that have still not been rehabilitated or closed. (Source: Auditor-General of South Africa)

Of the 1,170 identified mine “holings”, only 43% were closed and the department had not set specific time-frames to close the remaining holings (quarries, shafts and trenches considered to pose an immediate threat because of their proximity to residential areas).

Since the start of the government programme in 2006, only 12% (32 out of 261) asbestos mines had been rehabilitated.

Despite the 2038 target date to rehabilitate all 6,100 D&O mines, the level of annual funding allocated by the National Treasury was nowhere near enough to achieve this.

Ineffective leadership

What were some of the main reasons for this “slow progress”?

According to the report, ineffective leadership and oversight was one of the key reasons for delayed implementation.

Though the department was required to review and update its national strategy on a five-year cycle, it did not do so.

A new strategy had proposed alternative land uses for some of the abandoned mines, but the enabling National Mine Closure Strategy (NMCS) was only gazetted for public comment in May 2021 – more than 11 years after the national strategy set this objective

In December 2009, a rehabilitation oversight committee was established to oversee how the abandoned mines programme was managed, but the committee’s terms of reference were not approved.

“It also did not meet regularly, and did not execute all functions and track recommendations to assess the success of their implementation.”

Nor did the department establish whether the government was liable for 2,238 D&O mines identified as possibly having mineral rights that fell within the boundaries of licensed mining areas or private property ownership.

If any of these mines were confirmed as such, this could have reduced the department’s financial liability.

Strangely, several low-risk asbestos mines and holings were rehabilitated and closed in Limpopo, while many high-risk mines and unsafe holings were not attended to.

The reasons for this were unclear, the Auditor-General commented.

Now Maluleke has recommended that Mantashe’s department should review the national strategy and compile a new priority list to make more effective use of limited annual funding from the National Treasury.

Inadequate funding

A second major reason for slow progress was the inadequate level of funding allocated by the National Treasury.

“The allocated funding was prioritised to rehabilitate D&O asbestos mines, close holings, manage the database, and perform research and monitoring activities. As such, the budget did not include the rehabilitation of the other 2,322 high-risk commodity D&O mines.”

Until 2019, it also failed to develop effective communication strategies to deal with community unrest at several rehabilitation sites.

As a result, several rehabilitation projects had stalled for extended periods largely due to community demands for local labour to be used.

Examples included a project that was delayed for 134 days, leading to additional costs of R3,581,568. In Limpopo, some asbestos rehabilitation projects were stalled for more than two years.

Poor data- and record-keeping on abandoned mines were also identified as a weakness. In some cases, several mines had exactly the same GPS coordinates. The Council for Geoscience had not updated or loaded final completion certificates onto the database, while the department did not independently monitor the database to ensure information was complete and accurate.

No monitoring

Several failures had also been exposed in the department’s monitoring and maintenance projects.

For example, no monitoring was performed between 2009 and 2015.

From October 2015 to 2020, the Council for Geoscience was contracted to monitor asbestos D&O mines only, and it did not monitor any other D&O mines.

The council only monitored eight (25%) of the 32 asbestos mines that had been rehabilitated since the programme started.

In another case, rehabilitation work was completed at an asbestos mine in the Northern Cape in 2007, but the first post-rehabilitation monitoring was delayed for nearly 10 years. When this happened, monitors found significant problems (open, collapsed or subsiding shafts) and no corrective actions had started by late last year.

The department, for its part, submitted a formal response to the Auditor-General’s report in December 2021, indicating its commitment to implementing a number of initiatives to address the findings.

However, the department said it would only update the national D&O mine rehabilitation strategy after the finalisation of the National Mine Closure Strategy.

The department would also revise the rehabilitation project targets to align with historical budget and funding trends from the National Treasury.

It would immediately implement action plans to help the rehabilitation oversight committee fulfil its responsibilities and would conduct a study to quantify the government’s liability for all abandoned mines on the D&O mines database. DM/OBP

6,000 health and environmental ‘time bombs’ still to be defused – Govt decades behind schedule

A pile of poisoned fish dumped next to Loskop Dam after an acid mine leak at the abandoned Kromdraai coal mine. (Photo: Supplied)

By Tony Carnie | 08 Jun 2022

So little money has been allocated to cleaning up the legacy of the South African mining industry that it will take another 70 years to clean up just a fraction of the country’s more than 6,000 abandoned mines.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

There are roughly 6,100 “derelict or ownerless” mines scattered across South Africa, many of which can expose people and the environment to significant harm due to pollution of the air, water and soil.

Whether it is the tiny, needle-like asbestos fibres that slice up the delicate tissue inside human lungs; the acidic mine water that melts the organs of fish or the radioactive mining waste that can turn land and water into permanent “dead zones”, widespread pollution from more than a century of mining has saddled South African taxpayers with a hefty clean-up bill.

Yet the government is nowhere close to meeting its mine rehabilitation targets, according to a recent report by the Auditor-General that exposes 16 years of abject failure by Minister Gwede Mantashe’s Department of Mineral Resources and Energy.

For example, the department is only rehabilitating an average of three asbestos mines each year.

“At this rate, it will take approximately 69 years to rehabilitate the remaining 229 derelict and ownerless asbestos mines,” says the report

Auditor-General Tsakani Maluleke noted that the rehabilitation price tag for abandoned asbestos mines alone had been estimated at R3,860,741,741 (R3.8-billion) – and this figure excludes the clean-up and sealing costs for most of the other high-risk abandoned mines.

The brick and concrete ‘plug’ that was torn away by the pressure of acid mine water at the old Kromdraai mine in Mpumalanga. (Photo: Thungela Resources)

One example of how mines can literally “explode” came to light just a few months ago when large volumes of highly acidic water burst to the surface of the old Kromdraai coal mine near Emalahleni, Mpumalanga.

Sulphur-rich minerals are relatively harmless when left undisturbed below the Earth’s surface. But when exposed to water and air during mining, natural chemical reactions can produce sulphuric acid.

Unless this contaminated water is removed and treated, it flows up to the surface and escapes onto the land and surrounding rivers.

Dead fish

At Kromdraai, the pressure from acidic mine water tore apart a brick and concrete seal and left a trail of destruction that stretched nearly 60km along the Kromdraaispruit, Saalboomspruit, Wilge and Olifants rivers, before it was finally diluted in the upper reaches of the Loskop Dam.

At least three tonnes of dead fish were scooped up in the aftermath and it may take decades to restock these rivers and enable fish and less visible aquatic life forms to recover.

Closer to Johannesburg, acid mine drainage and dissolved uranium have created a radioactive environment that cannot support any life forms around the Robinson Dam on the West Rand.

The Auditor-General’s report also noted that South Africa has the highest rate of mesothelioma in the world. This is an aggressive form of lung cancer caused by airborne asbestos fibres.

Estimates showed that nearly 1.6 million people in South Africa live near, or next to mine waste dumps, exposing communities to windblown dust fallout that can lead to respiratory infection, heart disease and lung disease.

“People who live in post-mining environments with either partially rehabilitated or unrehabilitated asbestos waste dumps continue to be at risk of contracting asbestos-related diseases. There is no ‘safe’ level of asbestos exposure,” the report states.

This is one of the reasons why the Department of Mineral Resources and Energy had prioritised old asbestos mines and other high-risk mining operations for rehabilitation.

The Auditor-General notes that from 1991, the Minerals Act required mining rights holders to manage environmental impacts and rehabilitate the land surface.

The 2002 Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Act tightened up the law by requiring rights holders to fully rehabilitate mines before the department would issue a closure certificate.

This act also mandated the department to manage those mines that had been abandoned before 2002, (now known as derelict and ownerless mines).

The Auditor-General conducted an initial audit of the department’s mine rehabilitation programme in 2009, followed by a second audit in 2021.

“Although we recognise that the department has made some progress since the previous audit, there are still many critical areas that affect economical, efficient and effective rehabilitation and that need to be improved.

“Our audit revealed that the rehabilitation programme achieved only minor improvements over the past 12 years… with the average number of mines rehabilitated in a year increasing from 1.67 mines in 2009 to 2.25 mines in 2021.”

The Auditor-General also found that, despite the clear risks to several communities, the National Department of Health did not keep health-related statistics on the impact of unrehabilitated D&O (derelict and ownerless) mines.

Mantashe’s department had set a 2021 target date to rehabilitate about 2,000 large-scale mines considered to pose the greatest risks to society and the environment. The other 6,100 D&O mines were targeted for rehabilitation by 2038.

In stark contrast to these targets, however, none of the 2,322 “high-risk” mines was rehabilitated (apart from a handful of asbestos mines).

A graph showing the dismal progress in rehabilitating abandoned high-risk mines in South Africa. The red bar shows the number of mines that have still not been rehabilitated or closed. (Source: Auditor-General of South Africa)

Of the 1,170 identified mine “holings”, only 43% were closed and the department had not set specific time-frames to close the remaining holings (quarries, shafts and trenches considered to pose an immediate threat because of their proximity to residential areas).

Since the start of the government programme in 2006, only 12% (32 out of 261) asbestos mines had been rehabilitated.

Despite the 2038 target date to rehabilitate all 6,100 D&O mines, the level of annual funding allocated by the National Treasury was nowhere near enough to achieve this.

Ineffective leadership

What were some of the main reasons for this “slow progress”?

According to the report, ineffective leadership and oversight was one of the key reasons for delayed implementation.

Though the department was required to review and update its national strategy on a five-year cycle, it did not do so.

A new strategy had proposed alternative land uses for some of the abandoned mines, but the enabling National Mine Closure Strategy (NMCS) was only gazetted for public comment in May 2021 – more than 11 years after the national strategy set this objective

In December 2009, a rehabilitation oversight committee was established to oversee how the abandoned mines programme was managed, but the committee’s terms of reference were not approved.

“It also did not meet regularly, and did not execute all functions and track recommendations to assess the success of their implementation.”

Nor did the department establish whether the government was liable for 2,238 D&O mines identified as possibly having mineral rights that fell within the boundaries of licensed mining areas or private property ownership.

If any of these mines were confirmed as such, this could have reduced the department’s financial liability.

Strangely, several low-risk asbestos mines and holings were rehabilitated and closed in Limpopo, while many high-risk mines and unsafe holings were not attended to.

The reasons for this were unclear, the Auditor-General commented.

Now Maluleke has recommended that Mantashe’s department should review the national strategy and compile a new priority list to make more effective use of limited annual funding from the National Treasury.

Inadequate funding

A second major reason for slow progress was the inadequate level of funding allocated by the National Treasury.

“The allocated funding was prioritised to rehabilitate D&O asbestos mines, close holings, manage the database, and perform research and monitoring activities. As such, the budget did not include the rehabilitation of the other 2,322 high-risk commodity D&O mines.”

Until 2019, it also failed to develop effective communication strategies to deal with community unrest at several rehabilitation sites.

As a result, several rehabilitation projects had stalled for extended periods largely due to community demands for local labour to be used.

Examples included a project that was delayed for 134 days, leading to additional costs of R3,581,568. In Limpopo, some asbestos rehabilitation projects were stalled for more than two years.

Poor data- and record-keeping on abandoned mines were also identified as a weakness. In some cases, several mines had exactly the same GPS coordinates. The Council for Geoscience had not updated or loaded final completion certificates onto the database, while the department did not independently monitor the database to ensure information was complete and accurate.

No monitoring

Several failures had also been exposed in the department’s monitoring and maintenance projects.

For example, no monitoring was performed between 2009 and 2015.

From October 2015 to 2020, the Council for Geoscience was contracted to monitor asbestos D&O mines only, and it did not monitor any other D&O mines.

The council only monitored eight (25%) of the 32 asbestos mines that had been rehabilitated since the programme started.

In another case, rehabilitation work was completed at an asbestos mine in the Northern Cape in 2007, but the first post-rehabilitation monitoring was delayed for nearly 10 years. When this happened, monitors found significant problems (open, collapsed or subsiding shafts) and no corrective actions had started by late last year.

The department, for its part, submitted a formal response to the Auditor-General’s report in December 2021, indicating its commitment to implementing a number of initiatives to address the findings.

However, the department said it would only update the national D&O mine rehabilitation strategy after the finalisation of the National Mine Closure Strategy.

The department would also revise the rehabilitation project targets to align with historical budget and funding trends from the National Treasury.

It would immediately implement action plans to help the rehabilitation oversight committee fulfil its responsibilities and would conduct a study to quantify the government’s liability for all abandoned mines on the D&O mines database. DM/OBP