Why researchers Cruise and Sasada were right about Namibia’s natural resource management programme

Elephants on their way to a watering hole near the Namutoni camp in Namibia's Etosha National Park. (Photo: Media 24 / Gallo Images)

By John Grobler and Christiaan Bakkes | 08 Feb 2022

Elephants on their way to a watering hole near the Namutoni camp in Namibia's Etosha National Park. (Photo: Media 24 / Gallo Images)

By John Grobler and Christiaan Bakkes | 08 Feb 2022

A report on Namibia’s conservation policies has raised a storm — and accusations that its two researchers were biased and plain wrong. Here’s why we say they were absolutely correct.

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

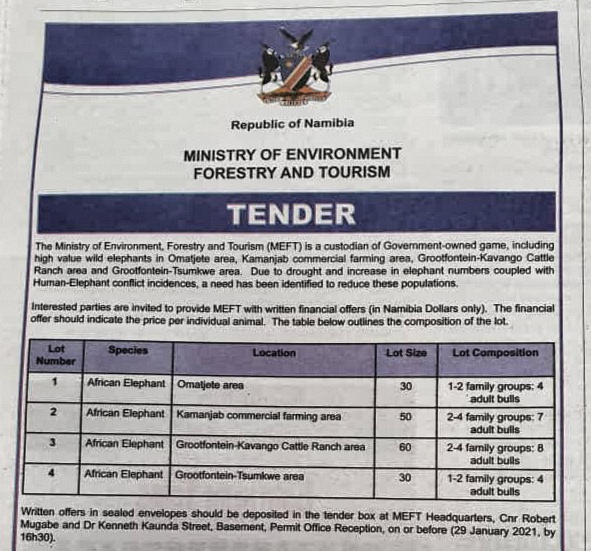

In December, Daily Maverick carried an article about a report on Namibia’s Community-Based Natural Resource Management (CBNRM) by two independent researchers, Dr Adam Cruise and Izzy Sasada.

They concluded that the programme’s perceived success of wildlife conservation and economic benefits for previously disadvantaged rural communities have been grossly misrepresented and is off the rails.

“Far from being a success story,” they said, “Namibia’s much-touted wildlife conservation model and its adherence to sustainable utilisation of wildlife through community-based management has, in fact, achieved the opposite of what is commonly presented.

The article was responded to by a group describing itself as Namibian Conservation Groups, consisting of 69 members of the Namibian Chamber of Environment, the Ministry of Environment and Tourism and The Namibian Association of CBNRM Support Organisations (Nacso).

They claimed the Cruise-Sasada report was done in bad faith, was illegal and unethical and was peddling an animal rights agenda to the detriment of Namibian people and animals. This is our response.

John Grobler

Nacso is a purely political vehicle for dispensing patronage in the form of hunting quotas among the Nacso membership as part of Swapo’s rural political strategies, which is more about the ruling party’s continued dominance than any form of sustainable conservation.

Nacso is noted for always generating its annual reports more than a year late, every year since its inception. Their excuse is the conservancies lack capacity. But after 12 or so years, why is that still the case if CBNRM was such a huge success?

This ad hominem attack on Adam Cruise and Izzy Sasada is thinly disguised as an academic debate that is more interested in winning the point than actually getting to the truth about CBNRM. This is becoming typical of the Namibia Chamber of the Environment being used by the ministry as an attack dog on critics of Swapo’s self-serving policies. They should be ashamed for letting themselves be used like this.

The truth is that the CBNRM model is the old campfire tyre that went flat everywhere they tried to run it in Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The reality is that you simply cannot infinitely sustain an exponentially growing human population on a rapidly shrinking wildlife population because, unlike humans, animal populations tend to remain constant over longer periods of time, as we saw with the elephant population in the Kruger Park.

This is especially the case with a wildlife population that has had to endure recurring droughts, increasing over-exploitation and above all, constantly increasing human encroachment.

Nature is not a business, however the Namibian pundits of CBNRM try to package it. Tourism is the price we pay for conservation. We are fools to think we can put the cart before the oxen and think it is somehow going to work out for any one in the long run.

Namibia has been eating the goose that lays the golden egg and, as a result, the once game-rich areas of Kunene are now denuded of almost any wildlife.

The “success” they claim in the northeastern areas has nothing to do with CBNRM, but everything with the seasonal migration of the regional animal herds trying to get back to more water-rich areas in Cuando Cubango.

There are also massive questions over the methodology used in the official game counts, which are all manipulated to exaggerate the numbers to justify ever-higher hunting quotas.

Pretty soon, there is going to be nothing left, like in too many other places in Africa. This is a Potemkin conservation model: all show but no real go.

Christiaan Bakkes

Adam Cruise and Izzy Sasada are just two more people in an increasing number of researchers, journalists and academics scrutinising and questioning Namibia’s CBNRM programme.

The list of names is getting longer: John Grobler, Frederico Links, Peter Pickford, Stephan Scholvin, Sian Sullivan, Stasja Koot, Paul Hebinck, Ingrid Mandt, Izak Smit and others.

Why are more and more people from different backgrounds, including investigative journalists, political scientists, sociologists, ecologists, conservationists and concerned citizens asking questions about CBNRM?

Why are members from within conservancies getting increasingly willing to speak out against irregularities and injustices? Questions asked from different angles seem to converge at the same conclusion. Has it not occurred to the Lords of CBNRM that all these different people may have a point?

In an article in The Namibian titled End of the Game in 2015, I investigated three issues. First, the black rhino poaching epidemic that started in 2012 and was still raging at the time of writing in 2015.

Second, the suspicious deaths of elephants and the fragmentation of the elephant herd at Purros. This herd was assumed to be safe because of the successful conservancies in the area.

Third, it criticised the “shoot and sell” policy, where outside contractors could come and kill desert-adapted wildlife in bulk after paying a sum to the conservancies. I questioned the wisdom of such an industrial practice in an arid environment.

In view of these three arguments, I asked the question if the CBNRM programme in Namibia’s arid North West was still on track. The article caused an international debate.

I was writing then as a supporter of the CBNRM programme. But after 20 years in the Kunene Region, I became concerned that greed and short-term benefits were eroding the original founding principles. I wanted CBNRM personnel and conservancies to take heed and redirect their vision while there was still time.

Instead, the issue blew up in my face and disrupted my life, with a conservancy association demanding my dismissal from my safari company of which I’d been an employee for 16 years. I was quick to learn that the CBNRM community suffers no criticism.

Shortly before then, my wife had been intimidated and pushed out of the conservation organisation she was leading because she dared to oppose the black rhino hunt planned by the government.

It has become a pattern — people critical of CBNRM policies are silenced and ousted. This makes it very difficult for an insider to speak out. Many are cowed, scared and intimidated into silence with threats of losing their jobs or their tourism concessions.

That’s why it is important for independent investigators and reporters to enter and gain evidence like Cruise and Sassada did.

I do not know them personally, but I believe their findings are sound and correct. The reason I say this is because my wife and I faced the very same conditions in northwestern Namibia’s communal conservancies from 2010 to 2018.

What we experienced was a danse macabre of dead animals, meat and wildlife products. On anti-poaching patrols, government conservation personnel and community game guards were more interested in shooting gemsbok for the pot than following rhino poachers.

Not only did their gunshots give away their position, all interest in catching poachers was lost after the gemsbok was in the pot. We found little or no adherence to designated quotas and it was commonplace to see a conservancy bakkie with one or more gemsbok carcasses on the back and a hunting rifle on the seat.

We witnessed a gemsbok being shot, wounded, chased and killed from a conservancy bakkie during a police investigation. We saw the white contractors slaughtering desert wildlife from their bakkies for their own butcheries.

They were driving indiscriminately over desert plains and firing into herds of gemsbok and springbok. At their camps, we witnessed kudu and zebra being butchered and loaded into freezer trucks.

We reported an incident where a professional hunter and his client wounded a giraffe in the belly, allegedly with a compound bow. It is illegal in Namibia to use a compound bow and arrow on a giraffe.

The giraffe collapsed in agony after a day and a half of suffering, only to be found after it expired. We confronted the hunters at the carcass. An independent bow hunter later confirmed our suspicion that the entry wound was from an arrow.

After we reported the incident to the NGO we consulted for at the time, our capacity for investigating similar irregularities was curtailed.

CBNRM has not ensured the implementation of laws, rules and regulations. There is no control. The communal lands of Namibia have turned into lawless places where people can come and take what they want. Conservancy committees and hunters have become a law unto themselves.

All of this is exacerbated by poaching and drought, because the lines have become blurred. The 2021 game count bears out these observations.

In 22 years of involvement in CBNRM in the Namibian northwest, I seldom experienced accountability, moderation and conservatism when it came to “sustainable utilisation” of wildlife. It’s simply not sustainable because there is no control.

The findings of Cruise and Sasada are merited. So are those of Frederico Links as well as Sullivan, Koot and Hebinck. It takes courage to stand up against injustice.

The reactionary bluster of the CBNRM community in its responses does not adequately address the real concerns of the lack of control measures in place. In being defensive, they divert attention from the real issues.

It’s not about pro-hunting or anti-hunting. It really is about the complete and utter lack of control. The growing evidence from several different fields of expertise demonstrates this.

Time is running out and warnings are not being heeded. The opportunities to remedy the situation are being missed because it has become just about defending hunting, not about implementing effective control measures with hunting.

Namibia’s once-booming tourism trade has been paralysed by a pandemic caused by the trade in wild animals and animal products. On top of that, wildlife numbers have crashed. Still, the pro-hunting and pro-wildlife-trade CBNRM community insists that their policies are sound. In fact, it simply lacks the capacity to execute control. DM/OBP

See:

A question of bias: Trophy hunting is a contentious industry and shaping research to get a desired outcome doesn’t help.

John Grobler is a Namibian veteran investigative journalist who has written for several Namibian and international newspapers such as South Africa’s Mail & Guardian, as well as The New York Times, Al Jazeera, The Guardian, and Le Monde Diplomatique. Grobler is a co-founder of the Forum for African Investigative Reporters, an association of investigative journalists in Africa established in 2004. He has won several awards over the years, most notably a CNN Africa Media award in 2008 for exposing the Mafia’s hand in the Namibian diamond industry, as well as in 2016 for exposing the role of Chinese and local business in the organised poaching of black rhino in Namibia’s Kunene Region.

Christiaan Bakkes led an anti-poaching unit as part of his military service and worked as a game ranger in the Kruger National Park. Thereafter he worked in the Damaraland desert as a guide and conservation official for Wilderness Safaris. In 2014, he was nominated as No 7 of the top 20 safari guides in Africa by Conde Nast Traveller. He currently works on education and advocacy projects with his wife Marcia, an environmental lawyer, on issues related to wildlife crime, environmental damage and social justice.