By Kevin Bloom• 1 April 2020 Limp

When Vasco da Gama anchored off the mouth of the Limpopo River in 1498, he named it Espiritu Santo. Around 520 years later, a Chinese businessman wanted by Interpol would do a deal with the South African government to build an 8,000ha Special Economic Zone on the river’s southern bank. The dealmakers would keep many secrets from the ancestral claimants to the land, including their unholy plans for a coal-fired power station.

I. Points of Power

There were many things that the 67-slide PowerPoint presentation failed to explain, but the most glaring omission was the likely impact on the Limpopo River.

There was, for instance, an artist’s impression of a 3,000-megawatt coal-fired power plant, but nowhere in the slides was there an indication of what this would do to Africa’s eighth-largest watercourse.

There were promises of a 20 million-ton coal washery, a 5.1 million-ton coking facility and a three million-ton steel plant, but the several million peasant farmers who relied on the river for irrigation did not warrant so much as a footnote. There was $1.5 billion earmarked for a ferrochrome plant and $1.2 billion for a stainless steel smelter, but there was no hint of a commensurate investment for soil and water rehabilitation.

Granted, the presentation did acknowledge in its introductory slide that the Limpopo River was just “30 kilometres away” from the project site, but this was only in the context of its waters acting as an “important source” of industrial cooling for the various plants and facilities.

Which, presumably, was one of the primary reasons that the presentation was kept hidden from the South African public.

Dated September 2017, its intended audience was almost certainly high-level investors and need-to-know government functionaries in South Africa and the People’s Republic of China. As the flagship project in a nationwide Special Economic Zone (SEZ) initiative that would soon be touted by the government as “the main driver of foreign direct investment” in the country, the quoted price-tag at the time of the Musina-Makhado SEZ’s launch was R40 billion — by January 2020, when opposition MPs were demanding answers in parliament as to the whereabouts of the environmental impact assessment, the number had ballooned to R145 billion.

A probable explanation for this disparity was to be found in the ever-growing ambitions of the project’s Sino-African architects, which in turn may have been another reason behind the secrecy. For at least five years, since the promulgation of the Special Economic Zones Act in 2014, the most that the average South African knew about these SEZs was that the model was perfected in the Chinese city of Shenzhen, that tax breaks and financial incentives were offered to investors and that they were supposed to kick-start ailing economies.

It was a significant breakthrough then, when, after more than a year of failed attempts, Daily Maverick gained access to a trove of official documentation on the Musina-Makhado SEZ. In the trove, a significant portion of which had been secured by the Centre for Environmental Rights under the Promotion of Access to Information Act, were internal government memos, lease agreements, MOAs, MOUs, licence applications and feasibility studies. Gathered together, the documents filled three lever-arch files. Were it not for the 67-slide PowerPoint presentation, the code in the paperwork may have been impossible to crack — as it turned out, the presentation was the master-key to the developers’ thinking.

The opening slide contained the EMSEZ logo, an abbreviation for the Energy Metallurgy Special Economic Zone, which a notice in the Government Gazette of March 2016 had designated as the official name for the Musina-Makhado SEZ. Aside from the plants and facilities mentioned above, the introductory overview promised a one million-ton ferromanganese plant, a 450,000-ton silico-manganese plant, a 450,000-ton limestone plant and a 300,000-ton ferrosilicon plant.

As noted in the tenth slide, inserted between these industrial monoliths within the SEZ’s 60sq km perimeter would be the fenced-off administration and living quarters. The buildings would include an office park for government agencies and banks, a 200-room five-star hotel, a 300-room three-star hotel, an apartment and residential complex and a “shopping mall, supermarket and farmer’s market”.

Again, since the presentation declined to address the potential impact of the SEZ on the millions of Africans from three sovereign nations who live downstream of Musina, the effect of the project on the lungs of its own financiers, managers and workers did not feature either. What was cited, however, was the name of one of the SEZ’s principal overseers.

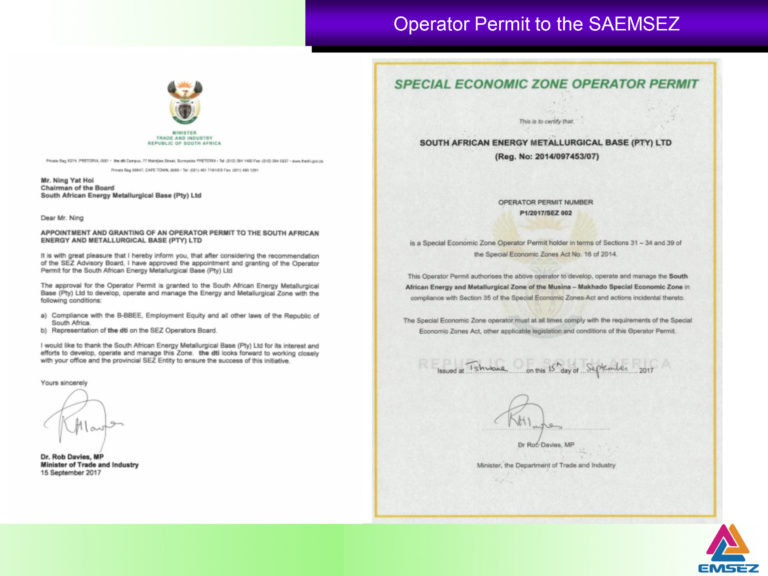

On the page preceding the introductory slide was a copy of a letter from South Africa’s then Trade and Industry Minister Rob Davies, signed and dated 15 September 2017. The letter awarded the operator permit for the SEZ to a Chinese-owned company called the South African Energy Metallurgical Base (Pty) Ltd. It was addressed to Mr Ning Yat Hoi, chairman of the company’s board.

Given that a copy of the permit itself appeared next to this letter — a document likewise signed by Davies, stipulating that the holder “must at all times comply” with the requirements of the SEZ Act of 2014 — it seemed a fair bet that Ning or one of his lieutenants would have been in charge of the roadshow.

Either way, in stating that an operator permit could only be suspended or withdrawn if “a law of the Republic [of South Africa]” had been contravened, section 36 of the SEZ Act may have granted a free pass to Ning. Because in the same month that the Department of Trade and Industry issued him the permit, the Zimbabwean authorities issued an arrest warrant.

The EMSEZ operator’s chairman, it was alleged, had ripped off the Bindura Nickel Corporation (BNC) and the Freda Rebecca gold mine, both owned by London-listed ASA Resources Group, to the tune of $2.76 million.

Ning denied the allegations at the time, and, in an emailed response to Daily Maverick’s questions — which included an attached letter to the BNC and ASA boards from his attorneys, promising that no expense would be spared in delivering justice to the spreaders of the “malicious rumours” — continued to protest his innocence. The amount, claimed Ning, was for the “repayment of a loan” owed by BNC to ASA.

“[If] you ought to know the truth,” he informed us, “the only legal and effective way is to go to the accounting firm Ernst & Young’s Zimbabwe office.”

Unable to get to Zimbabwe due to the travel bans brought on by the coronavirus, Daily Maverick was prevented from proceeding further with the matter. Nevertheless, as implicitly admitted by Ning and his attorneys, the arrest warrant issued by the Zimbabwe police “through Interpol” was still in force, subjecting him to “potential criminal detention”.

The other incontrovertible fact, at the time of this investigation going to press, was that Ning was still listed as the chairman on the EMSEZ website.

And so it was against the background outlined above that Daily Maverick visited rural northern Limpopo in mid-March 2020. Our purpose, since there appeared to be a slew of reasons to suspect irregularities on the intergovernmental level, was to ascertain what had been happening on the hyper-local level.

II. In the Dark

The interview with Mashudu Samuel Mulaudzi, former chairperson of the Mulambwane Communal Property Association (MCPA), was conducted on a quiet and pristine game farm about 40km south of Musina. Mulaudzi began the interview by explaining that the land from this farm “all the way to Waterpoort”, a small settlement in the shade of the Soutpansberg mountains, had been occupied by his people since at least the late 1700s.

“My great-grandmother’s mother is buried here,” he said.

Today, added Mulaudzi, though there were certainly many others, the clan could comfortably count about 500 members. These were the people that self-identified as Mulambwane because they “attended the community meetings”. Before 1913, he said, with the passing of the Union government’s infamous Land Act, the numbers would have been “a lot, lot more”. Mulaudzi also pointed out that the “GGs” — the apartheid-era government trucks, so named for the first two letters of their licence plates — had on a number of occasions removed members of the clan from their ancestral homesteads and dumped them by the side of the highway.

According to an internal government memo in possession of Daily Maverick, the post-apartheid state never disputed the claim of the Mulambwane clan to the baobab-laden bushveld that stretched either side of the N1 on its final run from the Soutpansberg to the Zimbabwe border. The land, comprising 112 farms, had been restored to the MCPA under the Restitution of Land Rights Act of 1994. The chief land claims commissioner had approved the handover in four phases, beginning in April 2009 and ending in June 2016. The purchase price for 16 of these farms, added the memo, was R72.07 million — which, of course, was the money paid by the government to the white farmers who’d been willing to sell.

Though no mention was made of the situation on the remaining 96 farms, the memo highlighted nine of the farms that had been acquired. These adjacent properties, which added up to 8,014 hectares in total, comprised the land that the MCPA had leased to the Limpopo Economic Development Agency (LEDA), the lead implementing agent for the Musina-Makhado SEZ and the government entity that held 51% of the project’s shares. The “rationale” for the lease, stated the memo, lay in the second state visit to South Africa of President Xi Jinping of China, when President Jacob Zuma had announced the creation of a “Metallurgical Cluster” in northern Limpopo.

“This is one of the flagship projects between the People’s Republic of China and the Republic of South Africa,” the memo declared.

What the memo did not declare was that the project would be powered by its own coal-fired plant. Dated February 2017, the document was essentially a request from LEDA to the Department of Rural Development and Land Affairs to approve the lease with the MCPA, but it gave credence to Mulaudzi’s contention that he “was not informed” about the power station. As far as Daily Maverick could tell, since the government’s internal communique made no reference to the power plant, the plan for its inclusion had not yet been drafted.

Most importantly, the lease agreement itself, which Mulaudzi had signed on behalf of the MCPA on 14 December 2016, did not mention the power plant either.

“They never told us about it officially,” Mulaudzi emphatically stated. “Unofficially, I only got to hear about it when I was shown the MOA between LEDA and PowerChina.”

This particular memorandum of agreement (MOA), which was concluded and signed on an unspecified date in 2018, was likewise part of the trove that had been handed to Daily Maverick. It was in fact a three-way agreement, with the South African Energy Metallurgical Base (SAEMB) as the third signatory — in this regard, the name and contact details of the man wanted for questioning by Interpol and the Zimbabwean authorities, Ning Yat Hoi, appeared on the final page.

The Beijing-based PowerChina International Group, stated the MOA, would construct a 3,000-megawatt coal-fired power plant of “ultra super quality” within the SEZ, with a “total estimated investment value … of around 4.5 billion USD”. While PowerChina would be the major investor and developer, LEDA and SAEMB would “assist with the necessary EIA approvals” as well as “solicit Eskom to become standby off-taker of surplus electricity”.

The MOA was unambiguous about the fact that the bulk of the electricity generated by the plant would be for the powering of the various industrial facilities, a clause that was perhaps the strongest indicator yet of the SEZ’s enormous proportions. It was further agreed, aside from “obtaining” or “facilitating” the granting of all requisite licences, that LEDA and SAEMB would “co-ordinate with local communities for all necessary issues”.

But Daily Maverick now had it on Mulaudzi’s authority, at least with respect to his own tenure as MCPA chairperson, that this last contractual promise had been contravened — an oversight that appeared in breach of the lease agreement between LEDA and the MCPA, too, specifically clause 9.5:

“The Lessee shall keep the Lessor apprised as to any material and relevant changes or amendments to the Lessee’s activities on the Property.”

Mulaudzi, who told Daily Maverick he would never have agreed to the deal had he known about the power station, had other reasons for regret. The negotiations with LEDA were “skewed”, he said, by which he meant they were not in favour of the Mulambwane community. As an example, he mentioned clause 10 of the lease agreement, which obliged the community to purchase various “immovable” SEZ properties — hotels, office blocks, residential apartments — after the lease expired.

“If we fail to buy the developments,” said Mulaudzi, “that means they can continue in perpetuity.”

The question, given that the relevant clause backed up Mulaudzi’s assertion, was obvious: why had he signed the document in the first place?

“I was under the impression that we would be able to sign two other agreements,” he said, “which included the 30% BEE stake. That’s what we had been promised, meaning that the Mulambwane people would hold 30% of the SEZ. That has never materialised.

“And then there was the second agreement, which promised 10% of the company that manages the SEZ.”

Indeed, in clause 1.1.2 of the MOA that Mulaudzi concluded with LEDA on 11 November 2017, provision was made for “project specific investment agreements”. Clause 1.1.11 of the same MOA went on to speak of a “preferential procurement plan” for the “advancement of designated groups as contemplated in the Preferential Procurement Policy Framework Act”.

Ultimately, said Mulaudzi, he had backed the SEZ because it promised major development and 21,000 jobs, in a region of the country where opportunities for employment and education had been hovering for years between scarce and non-existent. But his personal part in the effort to improve the lot of his people would come to an abrupt halt in August 2018, when, he alleged, he was unseated in a highly irregular MCPA election beset by government interference and a fraudulent transaction.

III. Denial River

Mulaudzi, it appeared, was not a man given to wasting time. Eight days after the formation of the new MCPA, he sent a letter to Rendani Sadiki, who was then the acting director-general of the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform. The letter laid out his allegations in a series of five concise points. Sent on 26 August 2018, two of these allegations were orders of magnitude more serious than the rest.

“The new committee fraudulently withdrew R100,000 from [the] coffers of the community and deposited the funds in their personal account … before they were even elected,” Mulaudzi asserted, drawing Sadiki’s attention to the attached “proof of payment”.

Then there was the allegation of election irregularities, which, Mulaudzi claimed, ran the gamut from “busing in ‘members’” to accreditation “being done by contestants”, the use of “two different verification lists” and the “barring of community elders for being in the wrong ‘camp’”.

When Daily Maverick contacted the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform for comment, we were forwarded a copy of the response that had been sent to Mulaudzi five weeks after his letter — a four-page official correspondence, dated 1 October 2018, in which acting chief director Fumani Mkhabela answered on behalf of Sadiki.

As far as the South African government was concerned, noted Mkhabela, the elections were “free and fair” and none of the officials had witnessed anything untoward. With respect to the accusation of fraud, Mkhabela encouraged Mulaudzi to lay a charge with the relevant authorities.

A little over two months later, Mulaudzi wrote back to Mkhabela — informing him, succinctly, that his advice had been accepted.

“The case was opened on 9 December 2018 at Mphephu SAPS,” this final letter stated, “with case number CAS 68/12/2018, following a resolution taken by the Mulambwane community at a meeting held on 8 December 2018 at Mudimeli Village, Dzanani.

“The matter includes misuse of state power by government officials resulting in dividing [the] community by verifying and empowering illegitimate individuals.”

At the time of this writing, as far as Daily Maverick could ascertain, the matter had moved no further than the case docket. But on 24 March 2020, Daily Maverick received a response to the set of questions that had been sent to LEDA. We may have hit a wall with the commanders of the Mphephu police station, but the SEZ’s lead implementing agent was a little more forthcoming.

Among other things, the response confirmed that the all-important MOA concluded between the provincial agency, PowerChina and SAEMB had indeed been signed in July 2018, at which point Mulaudzi was still the official MCPA chair.

To this end, Richard Zitha, LEDA’s chief project manager for the SEZ, denied that the 3,000-megawatt coal-fired power plant constituted a “material change” to the agency’s activities on the property in terms of clause 9.5 of the lease. Zitha did not provide a legal rationale for this assessment; he dismissed the allegation in a single sentence.

As for the other regrets that Mulaudzi had been harbouring about the lease, he was equally blunt.

“[The] MCPA was promised a 10% stake in the Property Management Company,” Zitha acknowledged, without elaborating on how or when this promise would become a reality. He then added: “We are not aware of any agreement regarding the 30% BEE stake, primarily because that is a private [matter] between the investor and any potential partner.”

In telephonic conversations with the two MCPA chairs that succeeded Mulaudzi — Thanyani Mariba, who served until August 2019, and the incumbent Tshimangadzo Tshubwana — no further light was shed on the local community’s engagement with negotiations around the empowerment stake. By the same token, Zitha did not respond to Daily Maverick‘s question about how the Mulambwane community would materially benefit from the SEZ, aside from the vague guarantee of jobs and the rental income from the land of R175,000 per month (around R350 per community member).

Finally, when it came to the coal-fired power MOA and its recognition of the authority of Mr Ning, Zitha’s answer was almost impossible to understand.

“The agreement with PowerChina was signed in July 2018,” he reiterated. “The agreement with SAEMB was signed in March 2017 and at that time we were aware [sic] of any Interpol related issue against Mr Ning.”

Although Daily Maverick had to assume that Zitha meant “not aware,” this did not detract from the fact that the MOA was apparently still in force: the one thing Zitha did not deny was that the SAEMB chairman was a fugitive from international justice.

But there was a much larger context to this Indra’s Web of accusations and denials, a theme that the lawyers at the Cape Town-based Centre for Environmental Rights had touched on in November 2019, when their “objections to the final scoping assessment report of the proposed Musina-Makhado SEZ” was sent to Zitha and others.

The final section of the CER’s objections — in a document that contained 132 highly detailed complaints — laid out why the entire public participation process had been “inadequate, unreasonable and unfair”. The lawyers did not use the word “illegal” in the section header, which was perhaps a mark of unnecessary restraint, because they made a pretty convincing case that the project’s Sino-African developers were in breach of section 2 of the National Environmental Management Act of 1998 (NEMA).

NEMA, they wrote, had made it clear that “the participation of all interested and affected parties in environmental governance must be promoted … and participation by vulnerable and disadvantaged persons must be ensured”.

Not only had the project’s proponents failed to adequately inform the local community of the “significant adverse health, climate and environmental impacts” that the SEZ was bound to have, noted CER, but the authors of the final scoping report had seemingly perjured themselves by declaring that two “civil society organisations” had participated in the consultation process.

As anyone familiar with the activist scene in South Africa would have known, the only civil society organisations worth mentioning in the field were Dzomo La Mupo (whose work Daily Maverick highlighted in February 2020) and the indomitable Wally Schultz’s SOLVE (Save Our Limpopo Valley Environment).

But, no doubt due to their reputations for punching way above their weight, neither of these outfits got anywhere near the team that drafted the scoping report. Instead, the so-called “civil society” organisations that LEDA did engage, by their own uncanny admission, were the Tubatse Municipality and Anglo-American Platinum.

At which point, it seemed that things were moving from the bizarre and unlawful to the downright ecocidal — a word, in this as in most cases, that was becoming synonymous with genocidal.

IV. Post the Apocalypse

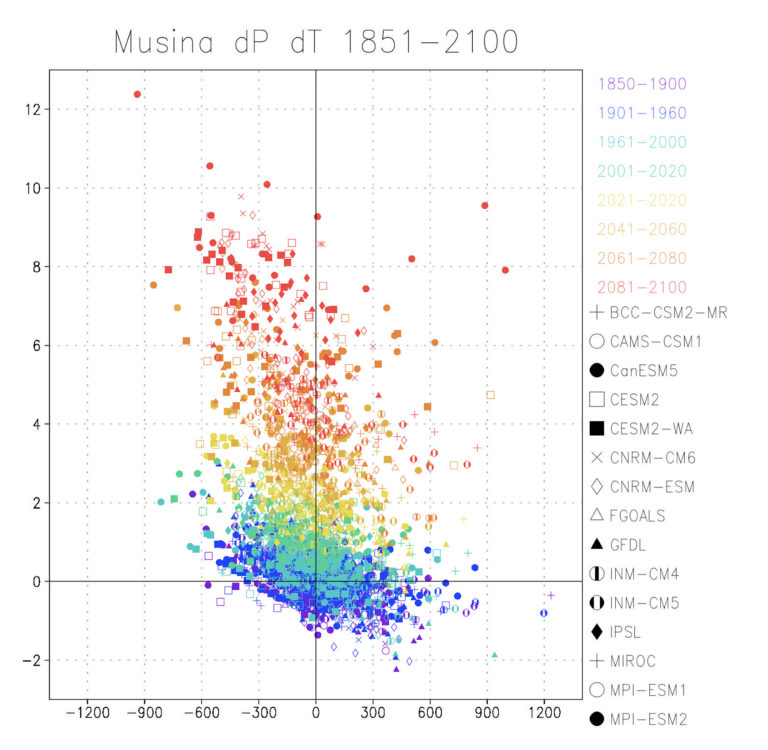

“By 2050,” the world-acclaimed South African climate scientists Bob Scholes and Francois Engelbrecht explained in a note to Daily Maverick, “the Limpopo valley will be about 4°C warmer than at present, and heat-wave conditions will persist for much of the year. The only way to do manual work under these conditions is at night, or in air-conditioned offices and machines. Air-cooling of industrial and mining processes will be increasingly inefficient and expensive. Ironically, it would be large CO2-emitting developments like this one that lead to that future. A liveable, agriculturally viable future for the Limpopo and the rest of South Africa requires that the whole world cease doing activities such as this.”

Temperature increase. Limpopo Province, 2020-2050. (Source: Global Change Institute, Wits University)

Those promised 21,000 jobs, then, were at best a farce — either the vast bulk of the SEZ labour force would quickly be declared redundant by automation, or they would increasingly work under conditions that made Emile Zola’s Germinal look like the Googleplex.

And that wasn’t even accounting for the solid waste pollutants, ground pollutants and non-CO2 air pollutants from the massive chimney stacks on the coal-fired plant and the various industrial facilities. It wasn’t accounting for the ecological process impacts on the surrounding wetlands and bushveld, which were already having a tough time supporting iconic species such as Cape vultures and baobabs. Neither was it accounting for the immensely compounded pressures on surface- and ground-water reserves in a region of the country where the Department of Water and Sanitation had been scrambling to avert complete infrastructural collapse.

All told, given the sheer scale of the Musina-Makhado SEZ, it was hard to see how anything in the Limpopo River valley would get out of the project alive.

This, of course, was the reason that the environmental impact assessment was so long overdue. It also may have been the reason that, in December 2019, Environment, Forestry and Fisheries Minister Barbara Creecy informed CER that she had no authority over the EIA — the “competent authority”, she wrote, was the Limpopo Department of Economic Development, Environment and Tourism, apparently because the “application for environmental authorisation” had been lodged by LEDA.

So no, it wasn’t looking good for the Limpopo River valley, particularly in light of LEDA’s handling of the scoping report. But behind LEDA stood the Department of Trade and Industry, whose answer to a parliamentary question in January 2020 was that the EIA had been “targeted for completion” by the end of the year. And somewhere in the orbit of the DTI, by the very nature of the governmental process, stood President Cyril Ramaphosa himself.

An awkward detail here was one of the few documents that CER had been “refused” in their PAIA request. The document was another MOU, which, according to the request sheet that CER shared with Daily Maverick, had been “signed between President Ramaphosa and the President of the People’s Republic of China in 2018 … in relation to commitments on co-operation in the fields of climate change, water resources [and] transport related infrastructure”.

The reason for refusing access to the MOU, stated the DTI in their response to CER on 26 September 2019, was that the document was not in their possession. But the department did not supply CER with an affidavit to this effect, as required by section 23 of PAIA, despite a formal request.

Which begged the obvious question: why did President Ramaphosa and President Xi Jinping of China even bother with the MOU? By November 2018, it was being reported in the South African press that “nine Chinese companies” had pledged a total investment in the SEZ of R145 billion, with LEDA holding “a 51% stake”. In the same report, it was noted that the Zimbabwean government — in which China had invested heavily — had agreed to supply water to the project from its own dwindling reserves. Ignoring the fact that these were the very Zimbabwean authorities who’d issued an arrest warrant for Ning, why were Ramaphosa and Xi pretending to care about climate change and water resources?

The answer, of course, was that they cared up to a point — like every head of state on the planet, barring one or two exceptions, their concern ended where economic imperatives began. And, in Ramaphosa’s case, by far the largest chunk of foreign direct investment in his country was coming from the People’s Republic of China, mostly as it pertained to investment in the Musina-Makhado SEZ.

Meaning, whatever was happening at the hyper-local level of the project, its ultimate driving forces were the international economic system and closed-door, top-tier geopolitics. Whether or not the ordinary citizens of South Africa would be able to prevail against these forces depended on a circumstance that nobody could have foreseen, being the outbreak of a global pandemic and its implications for the powers of the nation-state.

The dominant theory, at the time of this writing, was that since governments around the world — with the consent of their fearful citizenries — had rolled back on basic rights and freedoms in order to flatten the Covid-19 curve, these rights would be nigh impossible to claw back once the pandemic had done its worst. In this sense, it didn’t augur well that China was promising to soften its environmental protection laws in order to stimulate its post-coronavirus economy. Neither was it a comforting sign that the country was likely to emerge from the pandemic as the world’s leading superpower.

Still, to the horror of these self-same governments, the fear generated by the pandemic had a flipside, which was beginning to express itself in a global grassroots pushback — for instance, in the victories against eviction notices in the US, or the dissident voices in China that hadn’t been as loud since the showdown in Tiananmen Square.

The final victory, though, if the human species was ever again to thrive, would have to go to Nature herself. Conspiracy theories aside, the science was clear that not only did Covid-19 emerge from the international wildlife trade as manifested in the wet market in Wuhan, but that the transmission of diseases from wildlife to humans had been on a steep rise since 1960, when the wholesale destruction of forests, wetlands and grasslands had properly begun.

That said, next to the documents that the South African government didn’t want its people to see, the pandemic was just one more reason that breaking soil on the Musina-Makhado SEZ would be a monumental crime.

https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article ... po%20River