https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/special ... ino_files/

CITES RHINO FILES:

Death or glory for species on the ban wagon?

— By Tiara Walters —

Editing support by Kevin Bloom | Design by Bernard Kotze

The world’s surviving rhinos may be in a worse state than South African government figures are willing to admit. With the planet’s biggest conservation meeting kicking off this weekend, our last chance to save the species may be about to slip through our fingers.

Eight-thousand. That’s the number on everyone’s lips — from lekgotlas between private rhino owners to burgeoning rhino orphanages and the bloody anti-poaching patrols on southern Africa’s porous frontlines.

Eight-thousand. That’s both pro-traders’ and anti-traders’ rallying cry in the titanic ideological clash over the ban on the international trade in rhino horn.

That’s how many animals the global population of 20,000-30,000 African and Asian rhino has bled to the poaching splurge. In just 10 years. And the losses keep ticking upwards: 1,300 rhino slaughtered at private reserves; R2 billion a year to protect the surviving lot; a 70% drop in the value of live rhino from 2014-17; R1,47 billion shed by private reserves alone; a R9,8 billion asset loss to South Africa, so says the Private Rhino Owners Association.

Humanity’s grandest triennial wildlife hustle, the 18th global edition of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), holds the key to addressing the biggest question posed by this ban: to trade or not to trade.

Problem is, the CITES meeting — taking place in Geneva from 17-28 August after the Easter bombings scuppered it in Sri Lanka — probably represents the last chance for governments to have a meaningful face to face before the inglorious overlords of poaching finish off southern Africa’s last viable wild rhino.

Beyond that, we step into a void. The next opportunity is in 2022 — a near-eternity on the runaway rhinodometer.

Meanwhile, in the Lowveld

During a recent media tour to the Southern African Wildlife College on the Mpumalanga/Limpopo border with Kruger National Park, emotion hangs hot, heavy and humid over the simmering debate on trade.

The visit coincides with “poacher’s moon”, when the park’s rhinos are at their most vulnerable to the dazzling but deadly light of full moon.

At 4am on day two, a small party of journalists buckle over the side of a bakkie and into an unfenced training camp for anti-poaching patrols, near college HQ. As three nightwatchmen listen into the deep, black morning for a lioness and cubs who quietly padded through the camp minutes before, a more persistent and brazen danger is unfolding within the college’s patrol territory. In the following 24 hours, collaborative ground and aerial-enforcement ops twice interrupt the media programme, apprehending three poachers at two locations within the greater park. Three more individuals of the park’s already brittle rhino population are slaughtered, orphaning yet another calf.

Around the same time, K9 “honneman” Johan van Straaten’s high-stamina hound pack — or “my babatjies” (my babies) as he affectionately calls his charges during a demonstration — is involved in nabbing at least 10 poachers and removing three guns.

This war feels more gnawing in person than it may be possible to understand through the filter of our screens, not least because of the general dearth of long-form budgets that journalists desperately need to investigate and distil an issue that seems to be forever transfiguring.

“The anti-poaching units are doing a better job than ever before — we are so organised,” says college CEO Theresa Sowry. “But that doesn’t mean we’re winning. Poaching numbers are down, but is that because there are fewer carcasses to be found?”

There’s a terrifying nuance here. “We think there may be simply fewer rhinos to poach. Poachers have to work harder to find targets and the number of known incursions into the park, about seven a day, reflect this,” says Sowry. Hers is a review that may be more telling than the Department of Environment’s February rah-rah-good-news media release on 2018 poaching statistics, peppered with self-congratulations such as “significant progress”, a “decrease in rhino poaching” and the “first time in five years that the annual figure is under 1,000”.

“The reality of rhino poaching is evident when one looks at [past] census data. If we go back to 2010 at the start of the rhino-poaching crisis there were estimated to be over 12,000 white rhinos in the Kruger Park, the current figures are not clear as there is no official census data available,” the college reports in a 2019 newsletter. “However, by all accounts, and from our regular flights, rhino numbers in the park have declined substantially.”

It took the department several weeks to respond to repeated questions from Daily Maverick on why its poaching statistics appear at odds with on-the-ground observations that mortalities might be outgunning natural population growth. When we approached South African National Parks for up-to-date population census data in late July, its media team referred us back to the department. Finally, on July 31, the department released a statement asserting yet more anti-poaching “successes”.

We eventually got newly appointed Minister of Environment Barbara Creecy on the line on 12 August, thanks in no small part to dedicated co-ordinated efforts by her spokespeople.

“If you look at the figures for poaching in 2014 nationally, we were dealing with 1,215 rhinos poached. In 2018, 769 animals were poached,” she said. “Obviously, we would have concerns about the number of animals cumulatively poached from 2012 to 2018. It’s a huge number; and we have to be concerned about the long term-impact this will have on the gene pool of the species. At the same time, we have to acknowledge the incredible work done through integrated management and the significant work our rangers are doing on the ground. It’s dangerous and stressful and I had the opportunity to see it for myself.

“So I wouldn’t agree with you that we must be saying there are no rhino left — why are we spending all this money on protecting the animals if it wasn’t paying dividends?”

Asked if these dividends were based on new data — reliable and up-to-date population estimates — Creecy responded: “We are turning around the poaching. We haven’t released the new population figures. Do you think that if poachers knew how much rhino are left in Kruger that this would be a good thing?”

Her people slipped her information.

“According to the IUCN [International Union for the Conservation of Nature] Red List there has to be a census update every five years and, obviously, if we wanted to do it more often, we could,” she added.

The Kruger National Park population numbers most recently released to the public, according to the department’s September 2018 press release, were counted in 2017. This gives us a “likely” stabilised population of 586-427 black rhino in the park and a declining white rhino population of 5,532-4,759 animals. This also gives us a situation in which the global community at the 18th triennial meeting, or “CoP18”, is taking voting decisions on southern Africa’s rhino with old data at their disposal for the world’s largest rhino population — unless, of course, they’re miraculously privy to intelligence not yet seen by the public.

At least among some conservationists around the Southern African Wildlife College, there appears to be empathy towards the idea of international trade — “because nothing else has worked”.

During his dread slideshow of rhino mutilations, wildlife veterinarian Dr Pete Rogers, sweaty in his overall and close to tears of exhaustion after a day chasing poachers through the boiling bush, unleashes a volley of rhetorical questions when Daily Maverick asks about possible legalisation knock-ons. Could an incremental outward shift in the demand curve among a potential market of hundreds of millions of Asian consumers — and their diaspora — mean the end to the park’s dwindling rhinos? Do we even understand the fundamental nature of Asia’s shapeshifting demand, what fuels it and how to reduce it?

There’s no other way to put it: after performing rhino immobilisations since the start of the poaching crisis, this man is gatvol.

“Armchair conservationists love to talk about ‘demand reduction’. Reduce demand? How are you going to reduce demand? I want to vomit when I hear those words!” he spits at the room. “Imagine putting a bag of $200,000 under a tree in the veld, and telling people, ‘Don’t touch it!’ That’s exactly the same as having horned rhino on your property.”

If the tragedy of the commons is razing our natural heritage, this sense of desperation gives us the tragedy of dispossession, one in which the actors may be willing to entertain whatever it takes to wrench the rhino, their dwindling operational coffers and their sanity from evisceration.

Rogers’ frustration may not be misplaced, but demand-reduction campaigns to challenge controversial ideas about medical science — such as the so-called curative properties of horn — do matter. Sensitivities over cultural imperialism — the view that the West should work harder to accommodate differences in medical opinion with the East — also need to be weighed up against the significance of our global natural heritage. Awareness initiatives designed to reduce demand in the East for shark-fin soup claim effective results.

But, as the original purveyor of the two-tone khaki shirt might have said, whoever he (or, hey, she) was, “Mens klim nie op die preekstoel as die koeël eers deur die kerk is nie.” Don’t get on the pulpit once the bullet’s torn through the church. Or something like that — it’s moot whether rhino demand-reduction campaigns can work fast enough, but perhaps they would carry more moral authority if the West made an example of its own quackeries. Lining cat-litter boxes everywhere with astrology manuals would not be a bad start.

“If it’s not trade, what is it? Give us another solution,” pleads Rogers, throwing down the gauntlet.

Pro-trade states wade back into war

CITES’ 1976 founding meeting in Bern voted to place all five rhino species — black, white, greater one-horned, Javan and Sumatran — on “Appendix I”: this “listing” gives the most endangered wildlife and plants priority protection. It means a trade ban, or something like it, is in place for rhinos. (Rhinos for South Africa and Eswatini — Swaziland — then thought of as less-threatened, were voted onto Appendix II in 1994 and 2004 respectively.)

However, indicating growing appetite for international trade in rhino products, at least among key southern African range states, Namibia and Eswatini have both tabled trade proposals for scrutiny at CoP18.

Eswatini’s bid will once again ask CITES member states to consider more lenient regulations for the kingdom’s white rhinos, presently residing on “Appendix II” — the listing that accounts for “species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but in which trade must be controlled … ”

Here’s what Eswatini is really asking: selling “existing stock [of] 330 kg of rhino horn to [licensed] retailers in the Far East”, as well as horn from “sustainable non-lethal harvesting”. Proceeds from stock sales, “sold at a wholesale price of US$30,000 per kilogram”, could raise in the region of US$10 million for Eswatini, whose parks rely on “self-generated revenues to survive”.

“[Eswatini’s rhino parks] are struggling with the recent surge in costs — particularly the escalating security requirements,” its bid goes. “Proceeds will also be used to fund much-needed additional infrastructure and equipment, range expansion and to cover supplementary food during periods of drought … while also benefiting neighbouring rural communities and the nation at large.”

This year, Namibia also enters the fray, with an application that wants to shift that country’s white rhinos from Appendix I to Appendix II. Its proposal includes the mechanisms of legally hunted trophies out of the country. Besides, it’s a responsible custodian of an increasing white rhino population, Namibia avers, and lists among benefits of an appendix reclassification urgently needed financial dividends for anti-poaching, population-management and other conservation efforts.

Realpolitik bites

But headwinds may thwart southern Africa’s ambassadors of legalisation at CoP18.

Commenting on its politics of fervour, conservation economist Michael ‘t Sas-Rolfes notes that “CITES is not just a convention. It’s a culture. There’s a whole lot of backroom dealing, horse-trading, side payments and side deals going on. Vote for my proposal, and I’ll vote for yours.”

The conservation economist is an authority on endangered-species markets and co-author of the Department of Environment’s 2014 viability assessment report on legalising the domestic horn trade. A focal point of his present PhD research is the “moral psychology and tribalism” driving global conservation agendas — dominating one corner of the CITES ring, there are countries such as Namibia, the “quintessential and unambiguous pro-use country, with sustainable use of wildlife enshrined in its constitution”. Looming in the other, we have influential animal-rights groups with a habitually strong presence at each CoP, or the “generalised anti-use lobby”, as he calls them.

It was to this lion’s den at the most recent CoP — number 17, Johannesburg 2016 — that Eswatini petitioned its need for “limited and regulated legal trade” as essential upkeep for wildlife stocks that had become “too costly and risky to keep”.

Ted Reilly, the kingdom’s management authority for CITES and thought of by many as the father of Eswatini conservation, told the gathering of governments: “I feel like a rhino surrounded by poachers.”

It would seek a trading partner if its proposal was approved, Eswatini vowed. But its impassioned request was not enough. Of member states present in Johannesburg, South Africa and Namibia joined Eswatini’s ticket. But much of the rest — including Asian range states concerned about how international trade might affect their own rhino populations — voted against it. You could also say they wiped the proposal off the table.

In other words, at this year’s CoP, Eswatini may have a better chance of knocking out an army of Goliaths with a single ricocheting pebble to the beat of the Colonel Bogey March. Namibia, which simply wants its white rhinos to enjoy the same status as those in Eswatini and South Africa, may have a bit more luck.

Creecy told Daily Maverick that her department would send a delegation to CoP18. Although international trade in horn is “not currently part of our position”, she said, the department would act as something of a cornerman for the bidding countries, à la 2016.

“Eswatini is saying their population is well managed and that’s true. Our official position is based on Section 24 of the Constitution. When we talk about the sustainable use of the environment that means you must be able to conserve and you must be able to fund that conservation and you should not be involved in consumptive activities that would threaten the long-term viability of species in general,” Creecy said. “We differ from Kenya. They do not represent a sustainable use position; only a conservation position. Our populations of rhino and elephant are well managed in South Africa and those in Kenya are facing extinction. It’s a debate for environmental management and there are different views. We are also guided by support for our sister states in the SADC region where possible, and that’s because we have a globally respected conservation record in SADC.”

Private Rhino Owners Association chair Pelham Jones had every intention of being at the rescheduled meeting to bob and weave in the ring.

“PROA will attend CoP18 as an accredited NGO to not only give support to Eswatini and Namibia but to help educate parties on the unique conservation needs of Africa,” says Jones. His organisation brings some clout, representing most of the 7,500-odd rhinos on private land. Illuminating his motivations in 2019’s second issue of Wildlife Ranching Magazine, he adds: “It would be the greatest travesty if the needs of one nation are negated by the counter-vote of a nation that has no rhino, but has been influenced by radical NGOs or advisors who are not directly involved in rhino conservation, and who have little understanding of this complex problem.”

South Africa’s stewing question — to trade or not to trade

It’s not difficult to appreciate the tenuous balance of the department’s positions on trade, and why it’s sticking its head above the CoP18 parapet with only a proposal to increase South Africa’s black-rhino trophy quota from five to about nine surplus animals a year.

In 2014, although in principle not opposed to trade, the department’s viability report recommended upholding the national domestic moratorium. Key issues were wanting, it said, particularly proper control mechanisms; and clarity on how many horns were in private stockpiles. It may also have highlighted that permitting compliance among “some private rhino owners” was, well, rubbish.

Enter PROA member John Hume — the world’s largest rhino breeder, who says he currently has a roughly 1,700-strong population on his property — and fellow private rhino owner Johan Kruger. Just months after the department’s viability report, the two rhinopreneurs would successfully challenge the domestic moratorium in the Pretoria High Court on the grounds that the public weren’t properly consulted. In place since 2009, the moratorium now had been decisively shredded into a special brand of rhino feed.

In March this year the department announced its intention to compose a high-level advisory committee to review the recommendations arising from the 2015 committee of inquiry’s work. The late environment minister Edna Molewa had tasked the 2015 committee to investigate the feasibility — or not — of trade in rhino horn, and how this may relate to possible CITES proposals. This exercise helped produce the department’s views going into CoP18: “No immediate intention to trade in rhino horn, but maintaining the option to re-consider regulated legal international trade” when “key requirements” for security, community empowerment, biological and demand management, and incentives for rhino owners are met.

Jones believes it’s a “total misrepresentation by certain anti-trade NGOs that the privately owned reserves want trade opened to make money. Firstly, we are already over R1,47 billion out of pocket.”

Hume is one of several players champing at the bit under flagrantly expanding security costs: “If it were all above-board, we’d be happy to trade internationally,” he told Daily Maverick.

In April, elite police unit the Hawks caught two South African men north of Pretoria, near Hartbeespoort Dam, with at least 167 horns in their possession. Sheree Bega of the Saturday Star reported that, according to the unit, the horns “had been destined for illicit markets in South East Asia”. Describing what could be “one of the biggest reported seizures of rhino horns in South Africa”, Bega writes that the incident was linked to none other than Hume, who confirmed he had “legally sold 181 horns to a Port Elizabeth buyer”. The suspects were supposedly acting as the buyer’s “agents”.

Speaking to Daily Maverick by email, Jones says that “Hume has not been charged with any permit violation”.

“From what we have ascertained on the alleged permit violations is that Hume applied for and received permits from [the department] to sell a shipment of horn (as provided for in our legislation) and similarly the buyer applied for a Buyers Permit as well as Possession Permits and was issued these permits by [the department]. This process even includes a police and FICA clearance, what happened thereafter is in the hands of the SAPS and details will come out during the case against those charged.”

Suppose, for a minute, supply-side thinking is our best answer

Smoke and mirrors are what we have in the underground trade right now. It’s an almost inscrutable market that can make it nigh impossible to tell who is legal and who is not. Pro-traders argue that a legal market gives us a greater degree of transparency — both domestically and internationally — and becomes easier to monitor and engage with.

“Market prices would be visible, thereby allowing for continued and accurate monitoring of ongoing consumer demand relative to supply,” ‘t Sas-Rolfes tells us in his paper, The Rhino Poaching Crisis: A Market Analysis.

Writing in The Solutions Journal, he adds: “At present, most harvested horn is securely stored, adding to a South African stockpile that could already meet the equivalent of three to five years of current illegal supply.” Appropriately regulating supply from “sustainable” streams, such as routinely harvested horn from stockpiles we already have, as well as selected animals, may be our best answer “if law enforcement alone won’t solve the rhino-poaching crisis”.

‘t Sas-Rolfes’s thinking supports a version of classic supply-side economics touted by many a pro-trader: the price is likely to eventually come down if you increase the supply of a high-value product. If everyone is consistently flashing gold and diamonds — now worth less than raw horn (roughly ranging between $20,000 to upwards of the oft-quoted $60,000 per kilo) consumers value the product less. This, the theory goes, sooner or later reduces black-market profitability and poaching incentives.

However, ‘t Sas-Rolfes is at pains to point out to Daily Maverick that the supply-side model as defined by pro-trade arguments is often oversimplified, and notes another possible outcome, among a complexity of others: “What critics of this argument jump on immediately is that prices will come down. Prices won’t necessarily come down immediately. Prices could even go up — I personally consider it very unlikely, but it’s not impossible. Unless we make serious inroads into the demand by way of consumer-behaviour change, prices are never likely to come down sufficiently to eliminate the black market, because rhino horn as a commodity is simply becoming increasingly scarce. However, by reintroducing a sustainable supply, you are stopping the price from going up.”

There’s an “important part of the argument that a lot of critics miss”, he argues. In a legalised market, the “rhino owners and custodians are the ones now selling the horn, and they’re the ones who are making the vast amounts of money, which they then reinvest into protecting their stocks … where benefit flows devolve to local people, it’s a game-changer in terms of incentives [to protect rhino].”

There’s no downside to having a go at trade, proponents explain, because soon we may lose the last of our wild rhino, anyway.

But it’s also true that a species is not a bargain shop gambling chip, especially when it hovers at its critical threshold. Dr Ian Player’s Operation Rhino proved how the value of a couple hundred white rhinos would echo down the generations. Today Operation Rhino’s comeback kids number nearly 20,000 white rhinos — that’s 90-odd percent of the world’s remaining rhinos and the majority of our national herd. Addo Elephant National Park’s 600-plus (admittedly genetically compromised) elephants from 1930s salvage stock of just 11 individuals are now leaving every conceivable euphorbia bush trembling in their wake.

To criticism that legal international trade with farmed rhino is just too risky, ‘t Sas-Rolfes responds: “There are many precedents for successful, sustainable legal trading regimes that don’t threaten most wild populations of a species.”

Addax. Deer. Crocodiles. Ostriches. Vicuña. An alphabet of husbandry experiments that shout success.

When wild things make hearts sing

However, if a swallow doesn’t make a summer, and an orange isn’t an ocean liner, it follows that the slow-breeding rhino isn’t a crocodile that over a lifetime can pop out a thousand little crocs yielding compounded growth across each generation. Rhinos are also not least-threatened bottles of wine, nor the 5,4 trillion cigarettes that the tobacco industry spits out every year — so citing the necessity of relaxing prohibitions on such markets as comparable scenarios for rhinos come with a few problems. The necessary sale of human organs may be a more substantive comparison for a high-stakes ecotourism icon such as rhino. But, let’s bear in mind, the human kidney does not face the danger of extinction.

Banned or not, limited or abundant, for many consumers wild rhinos appear to be a special case — the final word in traditional Chinese medicine and luxury items. The more authentic the source, the more prized the product — especially in the case of jewellery. The vainglorious love nothing more than a bit of verboten — the so-called reverse-stigma syndrome.

Filmmaker and investigator Karl Ammann’s DNA-tested rhino samples from upmarket jewellery and artefact stores in China and Southeast Asia deliver insights into just how much consumers prize the real deal.

If Ammann’s samples from no fewer than 40 individual rhino represent a microcosm of the black market, we learn that jewellery from real horn appears to outweigh the popularity of faux medicine from rhino “lookalike sources”, such as critically endangered saiga antelope and less endangered water buffalo.

But here’s a mystery to pique the conservation sleuth in you: analysed by the Onderstepoort Veterinary Genetics Laboratory, only “two or three” of Ammann’s individual profiles would turn up in the lab’s RhoDIS DNA database, an index of some 20,000 rhinos. Where on Earth did the raw material originate?

Highlighting as possible supply sources anything from laundered and stolen horn to unrecorded poached rhino, Ammann’s work fingers a South African control system meant to register all privately owned live rhino as potentially being far from watertight.

“There is also the possibility that we brought back samples from Asia before the DNA from poached rhinos in Kruger and other places actually reached the lab, sometimes delayed by months if not years,” he added when speaking to Daily Maverick.

Ammann’s investigations also reveal how confounding the line between legal and illegal streams can be. If anything, it’s a cautionary tale of how demand for poached horn may eclipse what’s available.

Advanced among certain pro-trade supporters is the idea of a De Beers-type central selling organisation (CSO) owned by government, managed by skilled private-sector expertise and trading with at least one retail cartel. By defining price and volume, rather spinning in a free market run amok, this is a key aspect to the “Smart Trade” model, which calculates that a CSO could eventually yield “profits of R3 billion a year”. The profit estimate is not necessarily the issue — peer-reviewed research has valued a potential legal industry in the order of astonishing numbers.

However, Smart Trade’s model does make some utopian assumptions about possible partner governments’ ability, and will, to close down the illegal trade — when the local and international track record is not confidence-inspiring. By putting forward claims such as “there will be no room for corruption”, it assumes that obeying the model to the letter will eliminate corruption — “no corruption, no laundering”. Say what? As much as its trade framework could work, its starting position is, for now, not entirely sound: more flaw and order than the desirable alternative.

The wildlife and trade expert Annecoos Wiersema warns in “Incomplete Bans and Uncertain Markets in Wildlife Trade”, for the University of Pennsylvania Asian Law Review, that a cartel may even intensify “activity to try to compensate for the lower per-unit profit made for each specimen due to the newly flooded market”.

Disturbingly, awareness of a ban that may be finite or “subject to exceptions” could also inspire the peddlers “to speed up the process of extinction in order to ensure a higher price for stockpiled goods”.

‘A bladdy spaghetti bowl’

If your head hurts thinking about all this, moenie alleen voel nie, nè — don’t feel alone. One major rhino breeder who spoke to Daily Maverick on condition of anonymity called CITES’ text, and the ways in which traders may exploit it, a “bladdy spaghetti bowl”.

So, rather than saying the 1977 ban has not worked, let’s experiment with different phrasing and say the incomplete ban has not worked — or the “bladdy spaghetti bowl” has not worked — and interrogate how this perspective subverts the whole conversation. Especially when opportunists take advantage of a corruptible system.

What’s most important to appreciate here is that Appendix I species can be traded as commercially bred Appendix II species from registered captive operations, pending some paperwork and authority approvals. All this boils down to CITES’ captive-breeding clause, which the treaty says you may use with a view to the “recovery of [the] species” in “exceptional circumstances”. The clause amounts to a well-intentioned incomplete ban that can be abused as a pathway for black marketeering. Wild animals on Appendix I can be laundered as captive-bred products for commercial export. And, lest we forget the Spectre of the Vietnamese Pseudo Hunt. Aided and abetted by CITES permits, Vietnamese pseudo-hunters laundered hundreds of kilograms of rhino horn as legal hunting trophies out to the Asian black market between 2003 and 2010, as we discovered in Julian Rademeyer’s pivotal work, Killing for Profit. Round about that time, rhino poaching took on a life of its own. Since the pseudo-hunt debacle, the department significantly tightened its regulatory vice over Vietnamese syndicates in particular.

Botswana ecotourism entrepreneur Colin Bell sounds the dangers of what he calls “half bans”.

“This half ban we have in both the rhino and elephant worlds is the problem. Until we solve the real problem, which is that we have loopholes, and legal trade in South Africa and certain countries overseas, we can do what we want, but we’re not going to win. CoP18 must put all rhinos on Appendix I. There’s no compromise solution,” he told Daily Maverick.

Having investigated illegal trade in iconic species over several decades, investigator Ammann is also co-author of the seminal 2003 exposé Eating Apes, which blew the lid off the 1990s bushmeat trade in African great apes, all Appendix I species. Some of his more recent work exposes just how badly incomplete bans can go wrong when corruption filters into the captive-breeding clause.

“Massacring perhaps 1,500 great apes for bushmeat from 2006 onwards, a sophisticated criminal network ripped at least 160 chimpanzee and gorilla babies from their slain family groups, and rustled these traumatised youngsters into China’s zoo entertainment and pet industries,” according to Ammann. There were no captive-breeding facilities for chimpanzees and gorillas in Guinea, or Africa at large, at the time. “Several years into the butchery, both the CITES Secretariat and China’s CITES management authority would admit that they possessed incriminating copies of Guinean export and Chinese import permits.”

Instead of acting as a deterrent for permit fraud, the document-collaboration process between exporting and importing countries becomes an exercise in collusion. And that’s in the case of a high-profile species such as the chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) — a darling among reporters, news crews and non-profit fundraisers. What chances for exceedingly rare but trade-threatened Appendix I species most of us have never heard of, such as Madagascar’s ploughshare tortoise (Astrochelys yniphora) or Iran’s Luristan newt (Neurergus kaiseri)?

As first aid for a “failed situation” — thus, laundering run amok — PROA’s Jones suggests to Daily Maverick that “South Africa could apply for our white rhino to move to Appendix I or simply not issue export permits”. Products would be supplied with “certification and DNA history”, he adds. But he also notes that “the illegal market is already very well established and will not be shut down by prohibition or bans … ”

But here’s the rhino in the room, says Bell. “Studies conducted by [the department] have determined that South Africa can from stocks, shavings and future mortalities sustainably supply a maximum of five tons of rhino horn a year to a [market] that has historically been as high as 70 tons a year. Who will supply the balance?”

Demand for horn might outpace the species’ ability to regrow it, he indicates, as much as pro-traders like to underline the idea that horn is a renewable resource stemming from an animal that does not have to be killed, unlike elephant. “That’s the naiveté of some conservationists. If it doesn’t work, ‘We’ll just switch off the taps,’ they say. Ha! It doesn’t work like that!”

Trying to turn off the potentially messy business of international trade may be like offering your pawn as collateral once you’ve exposed your queen to a street-chess hustler.

“Uncertainty abounds” in endangered species markets, Wiersema warns. None of the above known-knowns, known-unknowns or unknown-unknowns might play out in reality. But perhaps nowhere is the precautionary approach more important than at this turning point in the rhino’s millennia-old biography — given the ideological importance of not losing the fight in the search for last-ditch solutions; the rhino’s cultural significance across the West-East divide; and its tightrope walk at the tipping point of ecological viability.

Even ‘t Sas-Rolfes, who is deeply informed about legal trade after 20-odd years of writing peer-reviewed papers on it, agrees “very little, credible, statistically significant data is available to allow for a rigorous market analysis”.

Can we just spit out a few thousand individual units of ecologically adapted rhino onto the conveyor belt of endangered species production if this poorly understood market — known to be irascible — surprises us by ploughing into remaining stock?

The search for solutions: pulling Friedmann’s Lever

Yup, the clamour of voices in the poaching crisis has become as heated as the 1920s hunt to plumb the workings of the cosmos itself.

In his 1977 account on the “search for the edge of the universe”, Red Limit author Timothy Ferris (not self-involvement guru Tim Ferriss of the four-hour workweek) describes the fanciful ideas that Roaring Twenties cosmology plucks from the “cosmos of the mind” to try understand Einstein’s static model of the universe.

“In clusters of chalked symbols, the cosmos bloomed like a flower, danced like a trained bear, warped and curved in an eerie calculus beyond the eye,” the cosmology writer recounts. Meanwhile, in Petrograd, we have Russian mathematician Alexander Friedmann “almost on the sidelines … poring over the mathematics of relativity” in the hope of finding an “unnoticed lever to be pulled”.

His peers are absorbed in the same — yet, it’s Friedmann’s universe that “ceases to be static and glides into motion” when he isolates the lever. This simply requires the mathematician to cross the Greek symbol lambda out of the equation. Like the universe itself, the thinking on this subject is constantly expanding, accelerating even — nonetheless, this lever was a beautiful solution that spoke to its time.

Taking a cue from the sleuths of the ultimate relativity whodunit, the temptation in the rhinoverse is to try match the extraordinary scale of the poaching crisis to equally grandiose solutions. Not least because this one does represent something big: an epoch-defining clash between East and West, based on our apparently irreconcilable views on how we should medicate our delicate space suits in a world apparently out to kill us.

Pro-traders vs anti-traders, if we are to corral them into different corners of the ring, which they seem to have done very well themselves, might often be at odds. But here are the takeaways they do seem to agree on, broadly.

Trade is no panacea

PROA’s intention with trade may be to “buy time for populations to grow”, Jones told Daily Maverick, but “trade is not the silver bullet and has to work as a composite together with other actions, such as better law enforcement [and] stronger political interventions”.

Proactive, not reactive, protection that integrates local shareholders

“Protecting populations at source is a sensible policy. Intercepting products destined for the market after harvest (e.g. once a rhino is already dead) is a lot less so, if at all,” says ‘t Sas-Rolfes. Where there’s slaughter, there’s inside information funnelling out to poachers — by the people who know the territory best, and that’s the locals — so due recognition of societies on reserve borders may help eliminate attitudes that marginalise people who matter a lot to rhino conservation.

‘Incentives to rhino owners to support continued investment in the conservation of rhino’

As per the 2015 committee of inquiry recommendations, increasingly beleaguered rhino owners, arguably the most critical guardians of remaining genetically viable stock, need eleventh-hour interventions, and reasons, to stay in the game.

Taking a leaf out of proven case studies — but heeding caveats

Bell’s “smorgasbord of solutions” echoes these ideas, offering a tightly linked, tiered plan that includes at-source protection through militaristic enforcement and community perks. He says that Rwanda’s and Nepal’s ecotourism models show quantifiable anti-poaching strides. Investment into Rwanda’s rural communities living close to parks, through aspects such as fibre optics, “even before Hout Bay and Bryanston”, are part of it. Last year the IUCN announced that Rwanda’s mountain gorillas were no longer critically endangered; and, in Nepal, a somewhat hopeful island of stalwarts amid a sea of illegal demand for horn, we now have 600 to 700 greater one-horned rhinos from a population of just 65 in the 1960s, and almost zero poaching. Still, recent community claims of torture by Chitwan National Park staff and 40-plus mystery deaths of the park’s rhino — let it be roundly understood — is the last story we want to replicate in South Africa.

Technology in keeping with the challenges of our time

Near the top of his list, Bell also cites a “mission-critical” whistle-blower fund to target the criminal syndicates who have been cruising around South Africa; and a “crack team to arrest and prosecute these guys, putting them away for a long time”. “In this plan, you’ve also got well-armed, trained, disciplined and paid security folks at the frontline. Add the best technology, and there’s much of it out there that allows you to see 12 kays into the distance. If someone’s coming at you, you see their sex and what weapons they’re carrying.”

Despite the department’s widely reported claims that its crackdown is producing the fruits of “success” because poaching “has continued to decline”, Creecy has indicated that she appreciates the urgency of reviewing “our efforts in the war on illegal poaching”. At the very least, the department concedes in its 31 July statements that “rhino populations cannot keep pace with current poaching rates”. “Together with our sister departments in the security and justice cluster, we need better controls at our ports of exit, more support in the war on the ground and faster prosecution of offenders,” Creecy said in her World Ranger Day address at Kruger National Park.

The widely deployed technology that would support such a doubling down can be prohibitively expensive, but Bell adds: “South Africa has got to get real. Do we want to be a Big Five country, or a Big Four country? Millions of South Africans depend on tourism. Are we willing to risk their livelihood and their ability to send their kids to school because we don’t have a crack investigative team?”

Some would call this a no-brainer. Or a Friedmann lever.

Gloves off

The quivering balance of South Africa’s conservation areas sustains 80% of Earth’s surviving rhino population. Put another way, in March this year we marked nearly 50 years since a group of US conservationists launched the now globally celebrated Earth Day. That hopeful moment, 1970, also marks the year since humans have killed nearly all the world’s rhinos — 90% of them.

But alongside the biodiversity impacts of climate change and the loss of landscapes, the poacher’s hacksaw is but one factor red-shifting rhinos — to paraphrase the poet Mary Oliver — away from their place in the family of things.

The debate, writes Jones, has been writ large “since 1992 in thousands of meetings, discussions and position papers, while rhino continue to be killed on a daily basis. It is now time to stop talking and to carry out bold actions to save one of the most iconic species in the world.”

“African and Asian rhino owners and custodians, global conservation NGOs and Asian consumers of rhino products should all ultimately share the same objective: to prevent the extinction of wild rhino populations,” ‘t Sas-Rolfes notes. “Are these groups capable of setting aside their differences and forging a mutually acceptable and sustainable solution?”

CoP18 could be the rhino’s greatest hope. Failing that, within the next few years the Secretariat may have little choice but to call an extraordinary general meeting for the first time in CITES history. That is, if new Secretary-General Ivonne Higuero is keen to avoid the Big Five’s final whistle on her watch.

© 2019. DAILY MAVERICK

Wildlife Trade - CITES Issues

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

- Richprins

- Committee Member

- Posts: 75407

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 3:52 pm

- Location: NELSPRUIT

- Contact:

Re: CoP18 in May Postponed to August 2019

Please check Needs Attention pre-booking: https://africawild-forum.com/viewtopic.php?f=322&t=596

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65938

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: CoP18 in May Postponed to August 2019

That was quite a bite

No obvious solution to the problem. What is CITES going to decide, is the question now Not an easy one

Not an easy one

There must be logical answer, but which is it

There must be logical answer, but which is it

No obvious solution to the problem. What is CITES going to decide, is the question now

That's crazy.... increase South Africa’s black-rhino trophy quota from five to about nine surplus animals a year.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5858

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: CoP18 in May Postponed to August 2019

Sam Ferreira, SANParks' large mammal ecologist on Cites, elephant management and ivory trade

http://www.702.co.za/podcasts/137/the-p ... tical-desk

http://www.702.co.za/podcasts/137/the-p ... tical-desk

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65938

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: CoP18 in May Postponed to August 2019

Ferreira is too difficult to understand also because there is a noise. It is most likely a telephone interview. I'm sure that we'll find it written somewhere later.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65938

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: CoP18 in May Postponed to August 2019

OP-ED

South Africa pushes for trade in endangered wildlife

By Andreas Wilson-Spath• 19 August 2019

South Africa, DRC, Namibia and Zimbabwe believe they should be able to sell threatened wildlife species on global markets, just like mass-produced trinkets.

The South African government, together with those of the DRC, Namibia and Zimbabwe, is proposing measures which, if enacted, could open the door to the international trade in elephant ivory, rhino horn and other endangered species.

In a submission to the eighteenth conference of the parties (CoP18) to CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) to be held in Switzerland in September 2019, the countries argue for a major overhaul in the way in which the organisation operates.

They believe they should be allowed to sell threatened wildlife species anywhere in the world in the same way that mineral resources and mass-produced plastic trinkets are traded on global commercial markets.

The changes to CITES they are asking for would pave the way for southern African countries to legally sell stockpiled ivory and rhino horn, which would put immense pressure on wild animal species already under severe threat of long-term extinction.

Unfair treatment?

One of the proposed amendments would make it easier to move species from one CITES Appendix to another. Animals and plants listed in the organisation’s Appendix I are effectively barred from commercial international trade, while those on Appendix II can only be traded under special circumstances.

The countries suggesting the changes claim to be victims of discriminatory CITES procedures, contend that trade prohibitions have not put an end to the illegal trade in wildlife products like rhino horn, and claim that “more and more species that are well protected in southern Africa and demonstrably sustainably used” are being “targeted” by “proposals from outside the southern African region” for transfer to Appendix I.

Making it faster and easier to move species such as elephants and rhinos from appendices that restrict trade is clearly one of the intended outcomes. The authors of the document argue that “progress has been extremely slow” on this front.

Other recommendations would bring CITES more in line with the World Trade Organisation’s General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a neo-liberal regulatory regime that facilitates unfettered access to global markets for commercial goods and services. South Africa and its partner countries claim CITES “provides for discrimination” and offers “no provisions against unfair trade practices”. They evidently believe that what they consider to be “discriminatory and trade-restricting measures” enacted by CITES could be successfully challenged under GATT rules.

According to Mary Rice, the executive director of the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), “the relationship between GATT and CITES has been explored at multiple CoPs between 2006 and 2013”.

“The parties to CITES rejected all recommendations submitted through that process, so we believe that no review is needed,” Rice said.

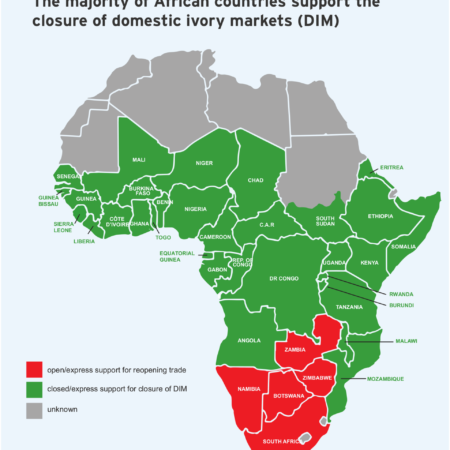

The proposal isn’t the only one pushing for trade liberalisation. Namibia wants the current protections on its population of southern white rhinos to be lowered, while Zambia, Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe want to be allowed to sell ivory internationally and Eswatini argues it should be permitted to trade in rhino horn.

But not all African governments agree. In sharp contrast to southern African proposals, 10 countries further to the north, including Kenya, Ivory Coast and Gabon want all African elephants to be moved to Appendix I in order to protect the species as a whole. Elephant populations in South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Namibia are listed in Appendix II. Conservationists contend that it makes little sense to classify animals of the same species in different appendices just because they happen to be found within the boundaries of a particular country, especially if those species are migratory and in overall decline across the continent, as is the case for elephants.

Anti-poor?

Charges that CITES is neo-imperialist, neo-colonialist and “definitely not pro-poor”, because its anti-trade policies deprive rural communities of the opportunity to “realise the full economic value of their wildlife resources” and starve conservation programmes of funds, would sound less hollow if they didn’t come from governments that have consistently shown themselves to be deeply corrupt, captured by powerful corporate interests and ineffectual at addressing some of the most basic grievances of their citizens — from crippling poverty to the non-delivery of services.

The sale of wildlife products in these countries is much more likely to benefit political elites and their cronies than the rural poor whose poverty the authors’ of the document invoke.

In a similar vein, their assertion that trophy hunting in southern Africa is “well-regulated” is extremely dubious in light of South Africa’s sordid record of canned lion hunting and the illegal killing of Cecil, Zimbabwe’s most famous lion in 2015, to name just two relatively high-profile examples.

As has become routine for ardent supporters of trophy hunting – an elite activity if ever there was one – they ignore the fact that non-consumptive ecotourism provides consistently higher economic benefits for a larger base of people than commercial hunting. What’s more, there is mounting scientific evidence that killing wildlife for trophies is not possible without detrimental effects on herds and populations.

Sustainable use or profit-driven exploitation?

In essence, the countries proposing these changes to CITES are upset that current rules prohibit them from deriving profits from wild animals which they consider to be valuable products that they should be entitled to harvest and sell as they see fit. They consider their autonomy unfairly restricted by regulations imposed on them by “ever so many armchair critics and self-proclaimed experts”.

At the most fundamental level, at the heart of this matter is a longstanding dispute over what is meant by “sustainable use” of wildlife. In a modern-day equivalent of enclosure, the countries proposing the changes to CITES consider all wildlife found within their borders to be their property and a commodity that they should be allowed to produce, harvest and sell competitively in markets around the world just as they are permitted to trade in ore and agricultural produce.

They contend that they are able to do so “sustainably” – without doing harm to, or causing the extinction of, species. Concerns about the conservation of wild animals in their natural habitat feature little in this view. To them, there is no discernible difference between species of wildlife and domesticated livestock, and they insist both should be exploitable as products for financial profit.

South Africa is one of the best examples of this philosophy in action. Over the past decade or so, the government, guided by economists promoting extreme free-market policies and the unrestricted commodification and commercialisation of nature, has succeeded in crafting laws and regulations that explicitly lay out this interpretation of sustainable use, for instance in the case of lions and rhinos.

The government-supported industry of breeding lions in captivity in South Africa provides an illustration of the outcomes of this philosophy. Supposedly proud of its global wildlife conservation status, the country now hosts more of these caged and commodified lions than live in its national parks and nature reserves.

The problem is that wild animals are not the same as commercial goods and lions bred in captivity for the sole purpose of becoming targets for wealthy trophy hunters and a ready supply of bones for the market in traditional Chinese medicine, are neither capable of surviving in the wild nor have any conservation value whatsoever. In fact, one could argue that they are no longer truly lions in an ecological sense.

An extinction crisis

Arguments by South Africa and others to expand international wildlife trade must be seen in the context of dire warnings from the scientific community. Earlier in 2019, a devastating UN report highlighted evidence that the exploitation of wildlife is a major threat to a global ecosystem that is being ravaged by species extinction at an extremely alarming and historically unprecedented rate. In light of this, international conservation organisations like Humane Society International are calling on world leaders to resist proposals for changes to CITES that would facilitate trade.

While conservationists agree that the meaning of sustainable use needs to be clarified within CITES, they do so for fundamentally different reasons to those offered by the authors of the proposal. They argue that wild animal species and nature as a whole cannot be treated as supposedly renewable resources and a form of capital that can be exploited indefinitely in simplistic economic terms. Any interpretation of sustainable use must be founded on ecological science, not on economic bottom lines.

Global biodiversity, healthy natural ecosystems and intact wilderness landscapes are not just beautiful and part of every human’s heritage, they are the very basis on which civilisation is built. They are not just “nice-to-haves”, but fundamental requirements for the survival of our own species. They are a common good that provides immeasurable benefits for all people across nation-state boundaries. Their intrinsic worth lies in the fact that they are our planet’s life support system. Do we really want to trade them away in exchange for short-term monetary gains which will end up mostly in the pockets of domestic elites?

“While CITES does have its shortcomings,” says the EIA’s Shruti Suresh, “it is currently the primary internationally binding treaty dedicated to addressing trade in animal and plant species of concern and we need to ensure that the precautionary approach is at the heart of any changes to the CITES framework”.

Given the current extinction crisis, we should do everything to protect endangered species, not expand ways to exploit them to their greatest commercial potential and it is extremely short-sighted and irresponsible for South Africa and other countries to make proposals that would diminish CITES’ effectiveness.

South Africa pushes for trade in endangered wildlife

By Andreas Wilson-Spath• 19 August 2019

South Africa, DRC, Namibia and Zimbabwe believe they should be able to sell threatened wildlife species on global markets, just like mass-produced trinkets.

The South African government, together with those of the DRC, Namibia and Zimbabwe, is proposing measures which, if enacted, could open the door to the international trade in elephant ivory, rhino horn and other endangered species.

In a submission to the eighteenth conference of the parties (CoP18) to CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora) to be held in Switzerland in September 2019, the countries argue for a major overhaul in the way in which the organisation operates.

They believe they should be allowed to sell threatened wildlife species anywhere in the world in the same way that mineral resources and mass-produced plastic trinkets are traded on global commercial markets.

The changes to CITES they are asking for would pave the way for southern African countries to legally sell stockpiled ivory and rhino horn, which would put immense pressure on wild animal species already under severe threat of long-term extinction.

Unfair treatment?

One of the proposed amendments would make it easier to move species from one CITES Appendix to another. Animals and plants listed in the organisation’s Appendix I are effectively barred from commercial international trade, while those on Appendix II can only be traded under special circumstances.

The countries suggesting the changes claim to be victims of discriminatory CITES procedures, contend that trade prohibitions have not put an end to the illegal trade in wildlife products like rhino horn, and claim that “more and more species that are well protected in southern Africa and demonstrably sustainably used” are being “targeted” by “proposals from outside the southern African region” for transfer to Appendix I.

Making it faster and easier to move species such as elephants and rhinos from appendices that restrict trade is clearly one of the intended outcomes. The authors of the document argue that “progress has been extremely slow” on this front.

Other recommendations would bring CITES more in line with the World Trade Organisation’s General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), a neo-liberal regulatory regime that facilitates unfettered access to global markets for commercial goods and services. South Africa and its partner countries claim CITES “provides for discrimination” and offers “no provisions against unfair trade practices”. They evidently believe that what they consider to be “discriminatory and trade-restricting measures” enacted by CITES could be successfully challenged under GATT rules.

According to Mary Rice, the executive director of the Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA), “the relationship between GATT and CITES has been explored at multiple CoPs between 2006 and 2013”.

“The parties to CITES rejected all recommendations submitted through that process, so we believe that no review is needed,” Rice said.

The proposal isn’t the only one pushing for trade liberalisation. Namibia wants the current protections on its population of southern white rhinos to be lowered, while Zambia, Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe want to be allowed to sell ivory internationally and Eswatini argues it should be permitted to trade in rhino horn.

But not all African governments agree. In sharp contrast to southern African proposals, 10 countries further to the north, including Kenya, Ivory Coast and Gabon want all African elephants to be moved to Appendix I in order to protect the species as a whole. Elephant populations in South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe and Namibia are listed in Appendix II. Conservationists contend that it makes little sense to classify animals of the same species in different appendices just because they happen to be found within the boundaries of a particular country, especially if those species are migratory and in overall decline across the continent, as is the case for elephants.

Anti-poor?

Charges that CITES is neo-imperialist, neo-colonialist and “definitely not pro-poor”, because its anti-trade policies deprive rural communities of the opportunity to “realise the full economic value of their wildlife resources” and starve conservation programmes of funds, would sound less hollow if they didn’t come from governments that have consistently shown themselves to be deeply corrupt, captured by powerful corporate interests and ineffectual at addressing some of the most basic grievances of their citizens — from crippling poverty to the non-delivery of services.

The sale of wildlife products in these countries is much more likely to benefit political elites and their cronies than the rural poor whose poverty the authors’ of the document invoke.

In a similar vein, their assertion that trophy hunting in southern Africa is “well-regulated” is extremely dubious in light of South Africa’s sordid record of canned lion hunting and the illegal killing of Cecil, Zimbabwe’s most famous lion in 2015, to name just two relatively high-profile examples.

As has become routine for ardent supporters of trophy hunting – an elite activity if ever there was one – they ignore the fact that non-consumptive ecotourism provides consistently higher economic benefits for a larger base of people than commercial hunting. What’s more, there is mounting scientific evidence that killing wildlife for trophies is not possible without detrimental effects on herds and populations.

Sustainable use or profit-driven exploitation?

In essence, the countries proposing these changes to CITES are upset that current rules prohibit them from deriving profits from wild animals which they consider to be valuable products that they should be entitled to harvest and sell as they see fit. They consider their autonomy unfairly restricted by regulations imposed on them by “ever so many armchair critics and self-proclaimed experts”.

At the most fundamental level, at the heart of this matter is a longstanding dispute over what is meant by “sustainable use” of wildlife. In a modern-day equivalent of enclosure, the countries proposing the changes to CITES consider all wildlife found within their borders to be their property and a commodity that they should be allowed to produce, harvest and sell competitively in markets around the world just as they are permitted to trade in ore and agricultural produce.

They contend that they are able to do so “sustainably” – without doing harm to, or causing the extinction of, species. Concerns about the conservation of wild animals in their natural habitat feature little in this view. To them, there is no discernible difference between species of wildlife and domesticated livestock, and they insist both should be exploitable as products for financial profit.

South Africa is one of the best examples of this philosophy in action. Over the past decade or so, the government, guided by economists promoting extreme free-market policies and the unrestricted commodification and commercialisation of nature, has succeeded in crafting laws and regulations that explicitly lay out this interpretation of sustainable use, for instance in the case of lions and rhinos.

The government-supported industry of breeding lions in captivity in South Africa provides an illustration of the outcomes of this philosophy. Supposedly proud of its global wildlife conservation status, the country now hosts more of these caged and commodified lions than live in its national parks and nature reserves.

The problem is that wild animals are not the same as commercial goods and lions bred in captivity for the sole purpose of becoming targets for wealthy trophy hunters and a ready supply of bones for the market in traditional Chinese medicine, are neither capable of surviving in the wild nor have any conservation value whatsoever. In fact, one could argue that they are no longer truly lions in an ecological sense.

An extinction crisis

Arguments by South Africa and others to expand international wildlife trade must be seen in the context of dire warnings from the scientific community. Earlier in 2019, a devastating UN report highlighted evidence that the exploitation of wildlife is a major threat to a global ecosystem that is being ravaged by species extinction at an extremely alarming and historically unprecedented rate. In light of this, international conservation organisations like Humane Society International are calling on world leaders to resist proposals for changes to CITES that would facilitate trade.

While conservationists agree that the meaning of sustainable use needs to be clarified within CITES, they do so for fundamentally different reasons to those offered by the authors of the proposal. They argue that wild animal species and nature as a whole cannot be treated as supposedly renewable resources and a form of capital that can be exploited indefinitely in simplistic economic terms. Any interpretation of sustainable use must be founded on ecological science, not on economic bottom lines.

Global biodiversity, healthy natural ecosystems and intact wilderness landscapes are not just beautiful and part of every human’s heritage, they are the very basis on which civilisation is built. They are not just “nice-to-haves”, but fundamental requirements for the survival of our own species. They are a common good that provides immeasurable benefits for all people across nation-state boundaries. Their intrinsic worth lies in the fact that they are our planet’s life support system. Do we really want to trade them away in exchange for short-term monetary gains which will end up mostly in the pockets of domestic elites?

“While CITES does have its shortcomings,” says the EIA’s Shruti Suresh, “it is currently the primary internationally binding treaty dedicated to addressing trade in animal and plant species of concern and we need to ensure that the precautionary approach is at the heart of any changes to the CITES framework”.

Given the current extinction crisis, we should do everything to protect endangered species, not expand ways to exploit them to their greatest commercial potential and it is extremely short-sighted and irresponsible for South Africa and other countries to make proposals that would diminish CITES’ effectiveness.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 65938

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: CoP18 in May Postponed to August 17th 2019

Elephants and Ivory Report CITES CoP18 – Analysis of Proposals and Documents

BY FONDATION FRANZ WEBER - DAVID SHEPHERD WILDLIFE FOUNDATION - PRO WILDLIFE - 16TH AUGUST 2016

PREVIEW AND OVERVIEW

The CITES CoP 18 begins tomorrow in Geneva, Switzerland and runs through 28 August. The CITES Secretariat reports that the 183 Parties to the Convention will consider 56 proposals submitted by governments to change the levels of protection of species of wild animals and plants that are in international trade.

Three of those proposals pertain to the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) and ivory poaching. Three other documents will consider: 1) trade in live African elephants, 2) management of ivory stockpiles, and 3) closure of domestic ivory markets. Summaries, links, and our positions and rationales of the proposals and documents follow.

PROPOSAL 10: Transfer the population of Loxodonta africana of Zambia from Appendix I to Appendix II

PROPONENT: Zambia

LINKS: Proposal 10. Analysis of Proposal 10.

SUMMARY OF PROPOSAL: Transfer the population of Loxodonta africana of Zambia from Appendix I to Appendix II subject to:

1. Trade in registered raw ivory (tusks and pieces) for commercial purposes only to CITES approved trading partners who will not re-export;

2. Trade in hunting trophies for noncommercial purposes;

3. Trade in hides and leather goods;

4. All other specimens shall be deemed to be specimens of species in Appendix I and the trade in them shall be regulated accordingly.

POSITION: OPPOSE

RATIONALE:

1. Would allow Zambia to export ivory. Any down-listing sends a message that ivory trade could reopen, fueling trafficking and threatening elephants across Africa and Asia.

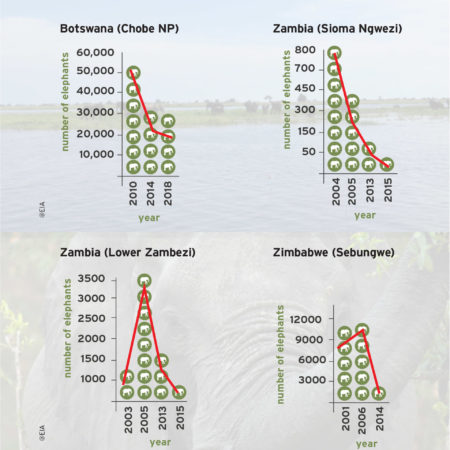

2. Population in Zambia experienced a marked decline from 200,000 in 1972 to 17-26,000 in 2015 and has not recovered. It still meets the biological and precautionary criteria for listing in App I. Proposal fails to mention extensive poaching in several areas. The CoP18 MIKE report notes a high poaching level in South Luangwa in 2018.

3. Governance is a serious problem. ETIS identifies Zambia as a concern due to large-scale ivory movements.

PROPOSAL 11: Amendment to Annotation 2 of Appendix II pertaining to the elephant populations of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe to enable resumption of trade in registered raw ivory

PROPONENTS: Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe

LINKS: Proposal 11. Analysis of Proposal 11.

SUMMARY OF PROPOSAL: Amendment to Annotation 2 of Appendix II pertaining to the elephant populations of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe to enable resumption of trade in registered raw ivory:

1. From government owned stocks (excluding seized and of unknown origin);

2. Only to trading partners verified by the Secretariat;

3. Proceeds only to be used to fund elephant conservation and community conservation and development programmes.

POSITION: OPPOSE

RATIONALE:

1. Would allow Botswana, Namibia, South Africa, and Zimbabwe to export ivory.

2. Will fuel demand, poaching and trafficking, and impact elephants in all range States. Ivory sales in 2008 led to a devastating escalation of poaching for ivory. On-going efforts to combat poaching and trafficking will be undermined.

3. Poaching is increasing in Southern Africa, including in Botswana (up 600% from 2014-2018) and South Africa. ETIS identifies problems with illegal ivory trade in all four countries, especially in South Africa and Zimbabwe.

PROPOSAL 12: Include all populations of Loxodonta africana in Appendix I through transferring populations of Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe from Appendix II to Appendix I.

PROPONENTS: Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Kenya, Liberia, Niger, Nigeria, Sudan, Syrian Arab Republic, Togo.

LINKS: Proposal 12. Analysis of Proposal 12.

POSITION: SUPPORT

RATIONALE:

1. The continental population declined by 68% from 1980-2015. Poaching remains high across Africa and is increasing in Southern Africa. Hot spots have moved from East Africa into Southern Africa (notably

Botswana) where over half of Africa’s elephants live.

2. As a highly migratory, transboundary species, CITES listing criteria should be applied to African elephants as a whole. CITES discourages split-listing due to enforcement problems.

3. Trading in ivory by some range States runs counter to agreed demand reduction efforts and endangers elephants in ALL range States.

4. The criteria for up-listing are met, in light of the “marked decline” (over 50% since 1980) and on-going poaching for ivory on a continental scale.

DOCUMENT 44.2: International trade in live African elephants: Proposed revision of Resolution Conf. 11.20 (Rev. CoP17) on Definition of the term ‘appropriate and acceptable destinations’

PROPONENTS: Burkina Faso, Jordan, Lebanon, Liberia, the Niger, Nigeria, the Sudan and Syrian Arab

Republic.

LINKS: Document 44.2. Analysis of Document 44.2.

SUMMARY OF DOCUMENT:

1. The position of the African Elephant Coalition is that the only “appropriate and acceptable” destinations for live wild elephants are in situ conservation programmes within their wild natural range. The submission proposes to include the guidance developed by the Animals Committee regarding the trade in live elephant specimens in an Annex to Resolution Conf. 11.20 (Rev. CoP 17), and supports the adoption of the Decisions proposed by Standing Committee 70.

2. Amendments are proposed to Resolution Conf. 11.20 (Rev. CoP17) seeking to restrict the definition of “appropriate and acceptable destinations” to “in situ conservation programmes or secure areas in the wild within the species’ natural range, except in the case of temporary transfers in emergency situations.”

3. The amendments also recommend that Parties put measures in place to minimize the risk of negative impacts on wild populations and promote their social well-being, as elephants are highly social with complex interactions that are indispensable to their well-being.

POSITION: SUPPORT

DOCUMENT 69.4: Ivory stockpiles: proposed revision of Resolution Conf. 10.10 (Rev. CoP17) on Trade in elephant specimens

PROPONENTS: Burkina Faso, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Gabon, Jordan, Kenya, Liberia, the Niger, Nigeria, the Sudan and Syrian Arab Republic.

LINKS: Document 69.4. Analysis of Document 69.4.

SUMMARY OF DOCUMENT:

1. Presents an overview of major ivory seizures and update on destructions.

2. Highlights lack of data on global ivory stockpiles, management challenges including theft and leakage into trade, and lack of progress with CITES guidance on stockpile management.

3. Recommends finalising and disseminating guidance for management of ivory stockpiles, including disposal, and draft Decisions that aim to ensure:

a. Parties comply with annual reporting on stockpiles in their territory, including on stolen / missing ivory;

b. The data are analysed and summaries published (at regional not country level); and

c. This important issue remains on the CITES agenda

POSITION: SUPPORT

DOCUMENT 69.5: Implementing aspects of Resolution Conf. 10.10 (Rev. CoP17) on the closure of domestic ivory markets

PROPONENTS: Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, Ethiopia, Gabon, Kenya, Liberia, the Niger, Nigeria and the Syrian Arab Republic.

LINKS: Document 69.5. Analysis of Document 69.5.

SUMMARY OF DOCUMENT:

1. Highlights the momentum for closing domestic ivory markets, notably in China, and role played by remaining legal markets, particularly in Japan and the EU, in perpetuating ivory trafficking.

2. Underlines the loophole in Resolution Conf. 10.10 (Rev. CoP17) specifying that only markets “contributing to poaching or illegal trade” should be closed, and provides evidence that Japan’s market contributes to illegal trade.

3. Recommends strengthening Resolution Conf. 10.10 (Rev. CoP17) through revisions that aim to ensure:

a) All Parties and non-Parties close domestic markets for commercial ivory;

b) Any trade under narrow exemptions is controlled;

c) Parties report annually on the status of the legality of their domestic markets and efforts to close them, and those that fail to close them are identified; and

d) The Standing Committee recommends action to secure compliance with provisions on market closure.

POSITION: SUPPORT

OUTLOOK FOR TOMORROW – Saturday 17 August

After welcoming addresses, negotiations will begin on administrative and financial matters, including rules of procedure, which could be controversial. More in tomorrow’s briefing.

# # #

CITES

CITES was established in 1973, entered into force in 1975, and accords varying degrees of protection to more than 35,000 species of animals and plants. Currently 183 countries are Parties to the Convention. The CITES Standing Committee oversees the work of the Convention during the two- or three-year periods between its Conferences of the Parties (CoPs).

Ivory trade

All populations of African elephants were listed on CITES Appendix I in 1989, effectively banning international ivory trade. But the protection was weakened in 1997 and 2000 when populations in four countries (Botswana, Namibia, South Africa and Zimbabwe) were down-listed to Appendix II (a less endangered status) to allow two sales of ivory stockpiles to Japan and China in 1999 and 2008. In 1980, the African elephant population was estimated at 1.3 million individuals – in 2015, only 415,428 remained according to the 2016 IUCN African Elephant Status Report estimates, a decline of 68 percent.

FFW, DSWF, PW, AEC

Fondation Franz Weber (FFW), based in Bern, Switzerland, has been campaigning for the survival of the African elephant and the complete ban of the trade in ivory for 40 years. FFW has had observer status at CITES since 1989 and has been a partner of the African Elephant Coalition since its creation in 2008.

David Shepherd Wildlife Foundation (DSWF) based in Guildford, UK, is a highly effective wildlife conservation charity founded in 1984 by wildlife artist and conservationist David Shepherd CBE FRSA (1931-2017) to help save endangered wildlife. DSWF works to fight wildlife crime, protect endangered species and engage local communities to protect their native wildlife and associated habitats across Asia and Africa. The Foundation focusses on maximum conservation impact by taking a long-term holistic approach to the issues surrounding the species that they work to protect, fighting for greater legal protection of endangered species, funding international cross-border enforcement programmes and building capacity of key law enforcement networks. DSWF also supports undercover investigations into wildlife crime and campaigns to bring an end to the trade in the parts of endangered wildlife.

Pro Wildlife (PW), based in Munich, Germany, is committed to protecting wildlife and works to ensure the survival of species in their habitat, as well as the protection of individual animals. This includes advocacy, strengthening national and international regulations and ensuring their implementation.

The African Elephant Coalition was established in 2008 in Bamako, Mali. It comprises 32 member countries from Africa including 27 African elephant range States united by a common goal: “a viable and healthy elephant population free of threats from international ivory trade.” The 32 member countries of the African Elephant Coalition are: Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Côte d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, The Gambia, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Liberia, Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Sudan, South Sudan, Togo, and Uganda. All AEC Members are Parties to CITES except for South Sudan.

BY FONDATION FRANZ WEBER - DAVID SHEPHERD WILDLIFE FOUNDATION - PRO WILDLIFE - 16TH AUGUST 2016

PREVIEW AND OVERVIEW

The CITES CoP 18 begins tomorrow in Geneva, Switzerland and runs through 28 August. The CITES Secretariat reports that the 183 Parties to the Convention will consider 56 proposals submitted by governments to change the levels of protection of species of wild animals and plants that are in international trade.

Three of those proposals pertain to the African elephant (Loxodonta africana) and ivory poaching. Three other documents will consider: 1) trade in live African elephants, 2) management of ivory stockpiles, and 3) closure of domestic ivory markets. Summaries, links, and our positions and rationales of the proposals and documents follow.

PROPOSAL 10: Transfer the population of Loxodonta africana of Zambia from Appendix I to Appendix II

PROPONENT: Zambia

LINKS: Proposal 10. Analysis of Proposal 10.