While big game animals such as lions, leopards, elephants, rhinos, and water buffaloes draw most visitors to Pilanesberg National Park, the land these animals live on is just as compelling. Pilanesberg is located in one of the world’s largest and best preserved alkaline ring dike complexes—a rare circular feature that emerged from the subterranean plumbing of an ancient volcano.

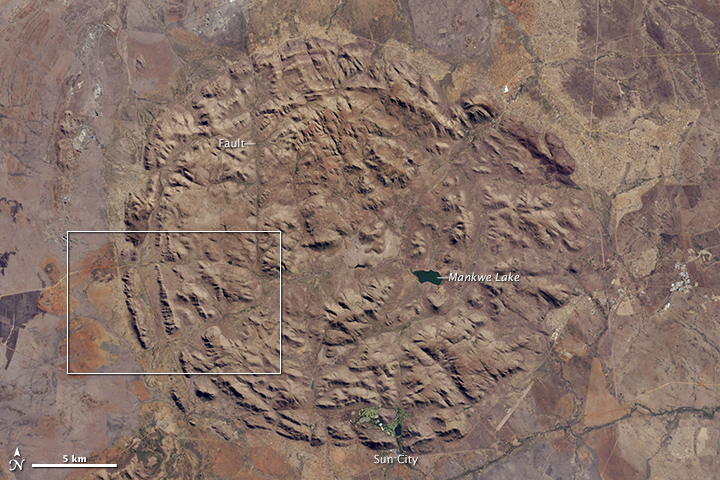

The Operational Land Imager (OLI) on Landsat 8 acquired this image of the park in South Africa on June 19, 2015. Seen from above, the concentric rings of hills and valleys make a near perfect circle, with different rings composed of different types of igneous rock. The entire structure sits about 100 to 500 meters (300 to 1,600 feet) above the surrounding landscape. The highest point—Matlhorwe Peak—rises 1,560 meters (5,118 feet) above sea level.

Several streams run through the valleys and faults, though most only flow during the wet season (between October and April). When this image was acquired in June 2015, the streams had run dry. However, man-made dams trap enough water to sustain critical watering holes for the animals. The largest body of water in the park, Mankwe Lake, is visible in the lowlands just east of the center.

Several phases of geologic activity created the landscape over hundreds of millions of years. The process began about 1.3 billion years ago, when primitive organisms like algae were the only lifeforms on Earth and huge volcanic eruptions were common. During this period, magma pooled up near the surface in a large hot spot that bulged with immense pressure. The pressure helped push up a volcanic structure that was several thousand meters tall.

Over time, tubes of magma radiated outward from the main magma chamber beneath the volcano. Eventually this created massive cracks in the Earth’s surface around the volcano at regular intervals. (In cross section, the magma tubes would have looked something like the branches of a tree extending from a common trunk. From above, the radial cracks gave the surface the appearance of a broken window. A good illustration of the magma tubes is available here.) After several violent eruptions sent lava bursting from the volcano, the center collapsed on itself, squeezing even more magma out from the network of cracks.

As volcanic activity waned, the remaining magma cooled in the cracks as bands of volcanic rock (mainly syenites and foyaites). Geologists call these structures dikes. The rate of cooling and the composition of the magma affected the type of rock that formed in each dike. For instance, white foyaite has particularly coarse grains and is formed when lava cools slowly. Red syenite forms when magma contains plenty of water. In the detail image, outcrops of white and green foyaite and of red syenite make up the ridges in the southwestern part of the park. These rock types are especially resistant to erosion and weathering, so they were left behind as hills and ridges while streams and glaciers scrapped and scoured away weaker types of rock.

References

Cawthorn, G. et al, (2015, March 6) Pilanesberg National Park, North West Province, South Africa: Uniting economic development with ecological design—A history, 1960s to 1984. Koedoe, 50 (1).

Carruthers, J. (2011, June 30) Geomorphological Evolution of the Pilanesberg. Landscapes and Landforms of South Africa, 39-46.

Jacana Education (2003) Pilanesberg Guide. Accessed July 17, 2015.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Photographs and caption by Adam Voiland.