Not the brightest bulb on the porch

Hunting in Botswana

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67388

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Hunting in Botswana

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67388

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Hunting in Botswana

Collared elephant hunted in Botswana, tracking device destroyed

Posted on December 14, 2019 by News Desk in the NEWS DESK post series.

NEWS DESK POST by AG Editorial

A collared elephant has been hunted in Botswana, and the tracking device destroyed. Four other elephant bulls were hunted by the same party. The hunts took place in a remote area near the Dobe border post between Namibia and Botswana.

The hunting party destroyed the tracking device, according to a statement by Botswana Wildlife Producers Association chairman Basimane Masire. He went on to say that the professional hunter and owner of the elephant hunting license subsequently forfeited their hunting licenses and have cooperated with the official investigation.

The Botswana Government’s Ministry of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation and Tourism confirmed yesterday that professional hunter Michael Lee Potter and Botswana citizen Michael Sharp, a citizen who holds the hunting license, claimed not to have noticed that the large bull elephant had a research collar around its neck.

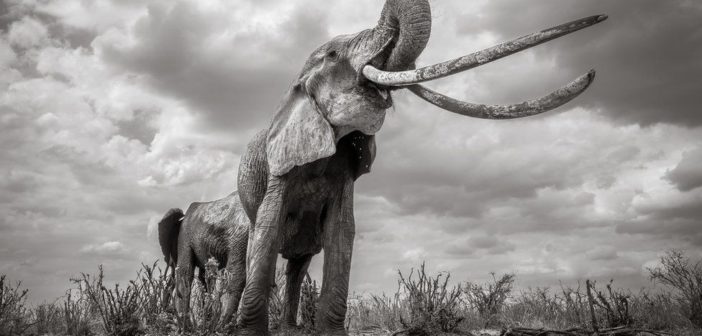

Collared elephant bulls are usually older animals with large tusks, making them attractive hunting trophies. Despite the hunting of collared elephants being contrary to most trophy hunting ethics protocols, and often illegal, incidents of this occurring are not infrequent.

Journalist Don Pinnock reported in Daily Maverick that Zimbabwe professional hunter Adrian Read had the following to say about trophy hunters claiming not to notice that their targets carried research collars: “The collar is very visible from the front as well as from the sides. And you wouldn’t shoot an elephant facing directly away from you because you have to assess the tusk size. In my opinion, anyone shooting a collared elephant and saying he did not see the collar can only be shooting after dark (which is illegal).”

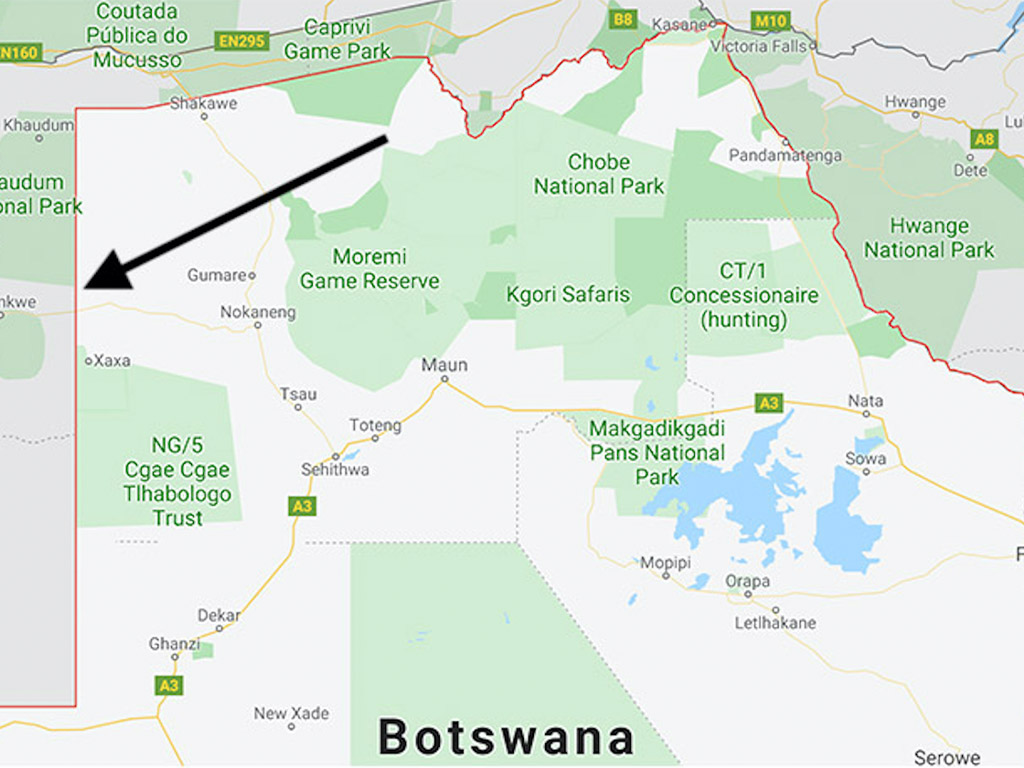

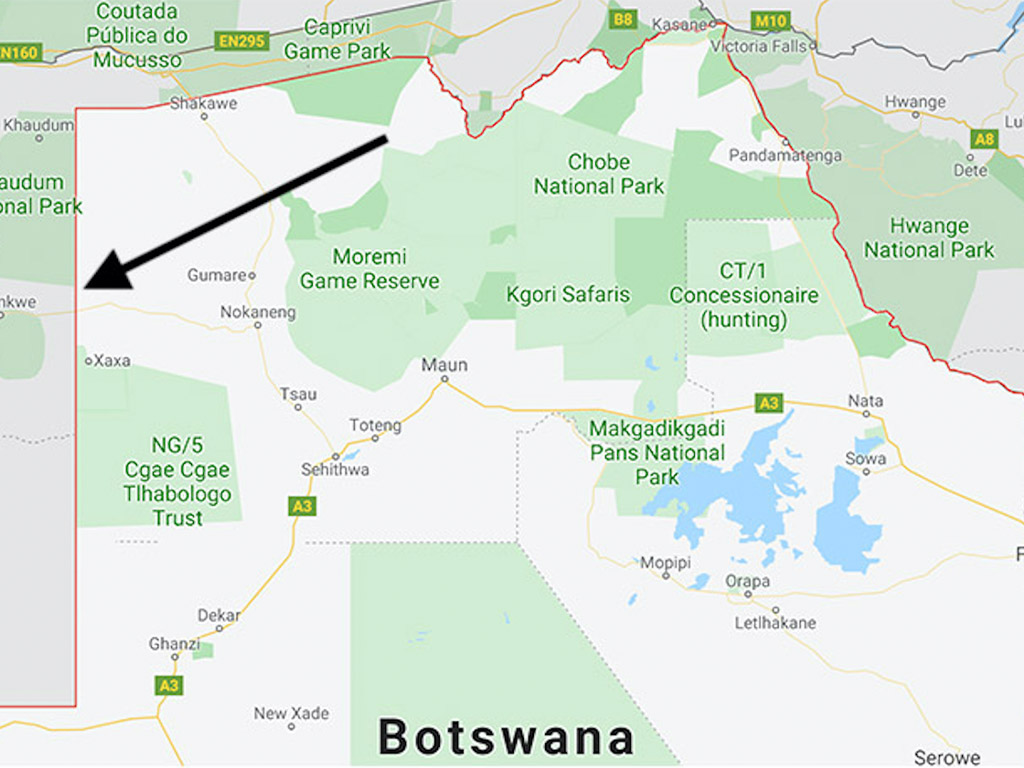

The elephant hunt took place in a remote area known as NG3, near the Botswana/Namibia border post of Dobe

Controversy has reigned since the Botswana government made the decision to resume the hunting of elephants, including chaos during the auction process when Botswana citizens had the opportunity to bid for elephant hunting permits.

Included in the reasoning provided by the Botswana government when they made this decision, was that elephants would be hunted in areas with high incidences of elephant-human conflict so that the local people derive benefits from the hunts. In his report, Pinnock continues that a representative of the local San people, Dahem Xixae, explained “We have no conflict. Only the hunters are the winners here, whereas local poor people remain in sorrow… There’s no benefit to the community from the hunting of elephants and there are dangers. First of all, the Ju/’hoansi do not eat elephants, because elephants behave like human beings. The five elephants hunted were not transients but local ones. This will make the (other elephants) more aggressive and if any were wounded they will be very dangerous to the local community.” Xixae went on to say that “his community was not advised of this elephant hunt”.

Posted on December 14, 2019 by News Desk in the NEWS DESK post series.

NEWS DESK POST by AG Editorial

A collared elephant has been hunted in Botswana, and the tracking device destroyed. Four other elephant bulls were hunted by the same party. The hunts took place in a remote area near the Dobe border post between Namibia and Botswana.

The hunting party destroyed the tracking device, according to a statement by Botswana Wildlife Producers Association chairman Basimane Masire. He went on to say that the professional hunter and owner of the elephant hunting license subsequently forfeited their hunting licenses and have cooperated with the official investigation.

The Botswana Government’s Ministry of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation and Tourism confirmed yesterday that professional hunter Michael Lee Potter and Botswana citizen Michael Sharp, a citizen who holds the hunting license, claimed not to have noticed that the large bull elephant had a research collar around its neck.

Collared elephant bulls are usually older animals with large tusks, making them attractive hunting trophies. Despite the hunting of collared elephants being contrary to most trophy hunting ethics protocols, and often illegal, incidents of this occurring are not infrequent.

Journalist Don Pinnock reported in Daily Maverick that Zimbabwe professional hunter Adrian Read had the following to say about trophy hunters claiming not to notice that their targets carried research collars: “The collar is very visible from the front as well as from the sides. And you wouldn’t shoot an elephant facing directly away from you because you have to assess the tusk size. In my opinion, anyone shooting a collared elephant and saying he did not see the collar can only be shooting after dark (which is illegal).”

The elephant hunt took place in a remote area known as NG3, near the Botswana/Namibia border post of Dobe

Controversy has reigned since the Botswana government made the decision to resume the hunting of elephants, including chaos during the auction process when Botswana citizens had the opportunity to bid for elephant hunting permits.

Included in the reasoning provided by the Botswana government when they made this decision, was that elephants would be hunted in areas with high incidences of elephant-human conflict so that the local people derive benefits from the hunts. In his report, Pinnock continues that a representative of the local San people, Dahem Xixae, explained “We have no conflict. Only the hunters are the winners here, whereas local poor people remain in sorrow… There’s no benefit to the community from the hunting of elephants and there are dangers. First of all, the Ju/’hoansi do not eat elephants, because elephants behave like human beings. The five elephants hunted were not transients but local ones. This will make the (other elephants) more aggressive and if any were wounded they will be very dangerous to the local community.” Xixae went on to say that “his community was not advised of this elephant hunt”.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67388

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Hunting in Botswana

Lifting Botswana’s hunting ban endangers its status as a global conservation leader

Opinionista • Dereck Joubert • 30 January 2020

In a world where global understanding of true conservation and the interconnectedness of all life on the planet is growing at an exponential rate, Botswana cannot afford to be seen as an increasingly retrogressive force on the planet.

Botswana’s unique natural wildlife heritage is one of the country’s greatest treasures. These vast, unspoiled wilderness areas are not only the cultural and environmental heritage of the Batswana people, but they are also primary areas in conserving increasingly fragile global ecosystems.

The people of Botswana are justifiably proud of their culture and of their exquisite natural heritage. They are also extremely aware of their country’s progress after more than 50 years of independence. Since 1966, Botswana has seen an average of 5% growth per year. Its per capita income has grown from some US$80 per year at independence in 1966 to more than $8,250 in 2018, according to World Bank data.

According to Unesco, it also has a largely successful basic education system that has some 90% of children enrolled in primary school and sees more than 96% of children go on to secondary school, leaving the country with one of the highest literacy rates in sub-Saharan Africa at 81%.

Botswana’s greatest challenge, however, is unemployment, which has been running stubbornly high for years at between 18% and 20%. This is partly due to an over-reliance on diamond production and a lack of industrial growth.

Botswana, though, remains one of the most stable, educated, democratic and prosperous countries in Africa. For all the decades of independence, this dependable stability has also seen wise and compassionate stewardship of the country’s wonderful natural splendours.

People from all over the world have come to Botswana to marvel at its unspoiled wildernesses and at the vast herds of animals that populate them. The World Travel and Tourism Council for 2019 (WTTC) reports that one in seven of all dollars in the country comes from tourism, and it generates 84,000 jobs or nearly 9% of total employment, making up more than 13% of the entire economy.

Wildlife tourism is by far the largest drawcard for foreign tourists. Again, the WTTC reports that 73% of spending came from international travellers and only 27% from regional holidaymakers.

Clearly, the country’s pristine wildlife reserves are more than a source of great pride and cultural history to Botswana’s people; they are an important source of economic prosperity and potential well-being.

However, the recent lifting of the ban on hunting, and specifically on elephant hunting, will endanger this critical natural and economic resource for Botswana.

Botswana’s own Tourism Statistics Report for 2017 (published March 2019) shows that, after visitors from South Africa and Zimbabwe (many of whom are day visitors visiting friends and relatives), the United States is the second-largest source of tourists to Botswana, making up some 26% of all visitors. A poll of registered voters in the US released by Humane Society International shows that an overwhelmingly large number of Americans polled do not support hunting elephants in Botswana. Some 75% believe that elephants should not be killed for trophy hunting, while an even stronger number (78%) are convinced that elephants should not be culled.

Already there is a petition being circulated on the internet asking the Botswana government to bring back the ban on elephant hunting. This is clearly a negative development for the country’s image as an ecologically sound destination.

Many argue that there are too many elephants in Botswana and that hunting them will help to reduce an excess population that is increasing. However, the African Elephant Status Report (AESR) published in 2016 shows that, in fact, the population of elephants in the country has decreased by some 15%.

Perceptions of human and animal conflict is a major driver of this lifting of the hunting ban, but not nearly enough work is being done to find non-lethal solutions to the problem, like, for instance, this study on appropriate land use patterns in Ngamiland for humans and elephants to live together.

Clearly, Botswana’s reputation as a country where animals are protected and treated ethically is already taking massive blows. In a world where global understanding of true conservation and the interconnectedness of all life on the planet is growing at an exponential rate, Botswana cannot afford to be seen as an increasingly retrogressive force on the planet. We should seek solutions that allow humans and animals to share our pristine wilderness without danger to humans or the necessity to kill them.

Such an approach would make us global leaders in a world where we increasingly understand that our survival as a species is linked to the survival of all life on the planet.

Opinionista • Dereck Joubert • 30 January 2020

In a world where global understanding of true conservation and the interconnectedness of all life on the planet is growing at an exponential rate, Botswana cannot afford to be seen as an increasingly retrogressive force on the planet.

Botswana’s unique natural wildlife heritage is one of the country’s greatest treasures. These vast, unspoiled wilderness areas are not only the cultural and environmental heritage of the Batswana people, but they are also primary areas in conserving increasingly fragile global ecosystems.

The people of Botswana are justifiably proud of their culture and of their exquisite natural heritage. They are also extremely aware of their country’s progress after more than 50 years of independence. Since 1966, Botswana has seen an average of 5% growth per year. Its per capita income has grown from some US$80 per year at independence in 1966 to more than $8,250 in 2018, according to World Bank data.

According to Unesco, it also has a largely successful basic education system that has some 90% of children enrolled in primary school and sees more than 96% of children go on to secondary school, leaving the country with one of the highest literacy rates in sub-Saharan Africa at 81%.

Botswana’s greatest challenge, however, is unemployment, which has been running stubbornly high for years at between 18% and 20%. This is partly due to an over-reliance on diamond production and a lack of industrial growth.

Botswana, though, remains one of the most stable, educated, democratic and prosperous countries in Africa. For all the decades of independence, this dependable stability has also seen wise and compassionate stewardship of the country’s wonderful natural splendours.

People from all over the world have come to Botswana to marvel at its unspoiled wildernesses and at the vast herds of animals that populate them. The World Travel and Tourism Council for 2019 (WTTC) reports that one in seven of all dollars in the country comes from tourism, and it generates 84,000 jobs or nearly 9% of total employment, making up more than 13% of the entire economy.

Wildlife tourism is by far the largest drawcard for foreign tourists. Again, the WTTC reports that 73% of spending came from international travellers and only 27% from regional holidaymakers.

Clearly, the country’s pristine wildlife reserves are more than a source of great pride and cultural history to Botswana’s people; they are an important source of economic prosperity and potential well-being.

However, the recent lifting of the ban on hunting, and specifically on elephant hunting, will endanger this critical natural and economic resource for Botswana.

Botswana’s own Tourism Statistics Report for 2017 (published March 2019) shows that, after visitors from South Africa and Zimbabwe (many of whom are day visitors visiting friends and relatives), the United States is the second-largest source of tourists to Botswana, making up some 26% of all visitors. A poll of registered voters in the US released by Humane Society International shows that an overwhelmingly large number of Americans polled do not support hunting elephants in Botswana. Some 75% believe that elephants should not be killed for trophy hunting, while an even stronger number (78%) are convinced that elephants should not be culled.

Already there is a petition being circulated on the internet asking the Botswana government to bring back the ban on elephant hunting. This is clearly a negative development for the country’s image as an ecologically sound destination.

Many argue that there are too many elephants in Botswana and that hunting them will help to reduce an excess population that is increasing. However, the African Elephant Status Report (AESR) published in 2016 shows that, in fact, the population of elephants in the country has decreased by some 15%.

Perceptions of human and animal conflict is a major driver of this lifting of the hunting ban, but not nearly enough work is being done to find non-lethal solutions to the problem, like, for instance, this study on appropriate land use patterns in Ngamiland for humans and elephants to live together.

Clearly, Botswana’s reputation as a country where animals are protected and treated ethically is already taking massive blows. In a world where global understanding of true conservation and the interconnectedness of all life on the planet is growing at an exponential rate, Botswana cannot afford to be seen as an increasingly retrogressive force on the planet. We should seek solutions that allow humans and animals to share our pristine wilderness without danger to humans or the necessity to kill them.

Such an approach would make us global leaders in a world where we increasingly understand that our survival as a species is linked to the survival of all life on the planet.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

-

Klipspringer

- Global Moderator

- Posts: 5862

- Joined: Sat Sep 14, 2013 12:34 pm

- Country: Germany

- Contact:

Re: Hunting in Botswana

https://conservationaction.co.za/recent ... ationists/

Hunting auction: Botswana government rides roughshod over conservationists 0

BY ROSS HARVEY - 18TH FEBRUARY 2020 - DAILY MAVERICK

The Botswana government has auctioned off the last of its big tuskers to hunters despite offers from conservationists to buy the licences to save the elephants.

There are probably fewer than 100 big tuskers left in Africa. In its haste to sanction elephant hunts despite offers to save them, the Gaborone government is ignoring both the critical role elephants play in maintaining healthy ecological systems and the future of elephants on the continent. Instead, it’s selling its inheritance for short-term income from an extractive industry.

At a major hunting auction on 7 February, six of the seven packages (of 10 elephants each) were sold to the same white-owned hunting companies that benefited from Botswana’s hunting industry before the 2013 hunting moratorium. One package failed to reach the reserve price.

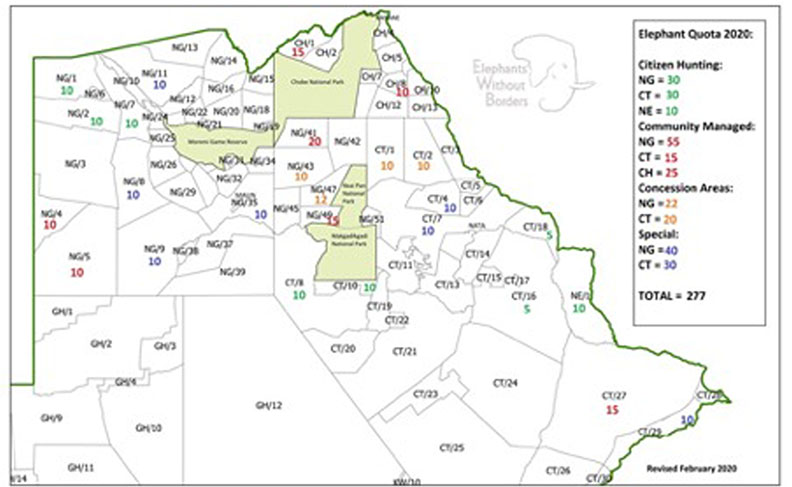

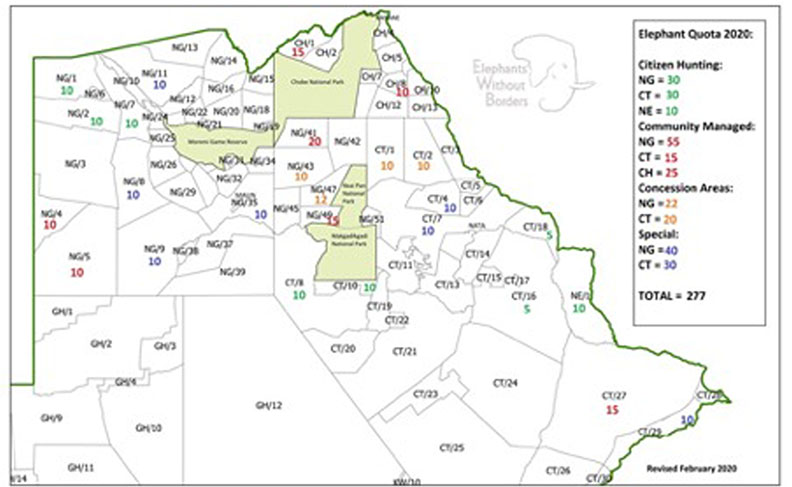

These 70 licences form the “special elephant quota” of the 2020 hunting quota of 272 elephants. Advertisements for the auctions were only released to the public on 3 February. Interested bidders then had only until 7 February to register – at best an indication of the rushed way in which the reintroduction of hunting to Botswana has been managed; at worst, an indication of pre-decided outcomes.

The EMS Foundation, a South-African based conservation advocacy and research organisation, attempted to bid for the licences. It wrote a letter to Dr Cyril Taolo, the director of Wildlife and National Parks, requesting a revision of the qualifying criteria “to enable us to bid on the hunting packages on the 7th of February 2020 with the express intention that the elephants included in these packages are not hunted should our bids be successful”.

The letter further noted that “we wish to purchase available licences with no intention to hunt elephants, but for the money to be appropriately distributed in a way that benefits conservation”. Local communities would therefore not be deprived of the revenue that would otherwise accrue through auctioning off elephant hunts. Of course, the hunting outfitters would lose out, but communities would have cash in hand, provided appropriate governance mechanisms were established through which to equitably distribute the revenue.

The letter objects to the fact that the bid criteria “explicitly excludes tourism operators or foundations/companies such as ours that do not want to hunt elephants but do desire to fund non-consumptive conservation in Botswana”. Beyond the EMS Foundation, other donors offered funding to buy 10 elephant hunting licences on auction to prevent the animals’ deaths. Clearly, those who are willing to invest directly in conservation activities, and even subsidise revenue shortfalls in areas where non-consumptive tourism is apparently unviable, are overtly excluded from the bidding process.

The licences on auction were 10 each for areas CT4, CT7, CT29, NG8, NG9, NG11 and NG35. Ngamiland concessions 8, 9 and 11 are held by local communities.

Local communities in NG3 objected to hunting in their concession (where a hunting disaster occurred in 2019 involving the shooting of a collared research bull). Consequently, there is no 2020 quota for NG3, but the quotas for some of the neighbouring concessions appear too high.

There has also been no consideration given to maintaining hunting-free corridors in critical areas such as NG41, which will be auctioned later. This suggests that the quota is not based on science; the way in which it has been divided up is arbitrary. Moreover, a confidential letter from a community in NG8 has expressed to the government that it does not want hunting, which it sees as undermining its projects to raise support for building self-sustaining tourism initiatives. If there is science to support the quota and the way in which it has been allocated, this should be made publicly available. Until such time as this is provided, it would appear responsible for the international community to ban trophy imports from Botswana.

The results of the auction are telling. Six 10-elephant packages sold for between $330,000 and $435,000 each. The package for CT29 did not sell because it did not fetch the minimum clearing price. The government amassed a total of $2,355,000 for six packages. There is no indication of how this money will be spent.

Successful bidders will now look to sell elephant hunts for upwards of $60,000 per elephant, normally paid into foreign bank accounts. At an average cost of $39,250, the margins are impressive. But who will benefit? Hunters would have us believe that local communities are the primary beneficiaries. However, one study showed that only 3% of hunting revenue eventually trickles down to them; at best hunting only contributes an average of 1.8% of African tourism revenue.

CT4 and NG9 both went to Jeff Rann Safaris, which is now offering a 10-day elephant hunt for $85,000 on its website. A joint shareholder is Professor Joseph Mbaiwa of the Okavango Research Institute who has long been an advocate of lifting the Khama-era moratorium on hunting in Botswana. Mbaiwa became a shareholder (in November 2019), shortly after President Mokgweetsi Masisi decided to bring hunting back to Botswana last year. CT7 went to Leon Kachelhoffer, NG8 went to Clive Eaton (along with NG11, in partnership with Kaz Kader). NG35 went to Grant Albers (apparently for Kerry Krottinger, a Texas oilman with a long history of big game hunting in Africa). There are no obvious local community beneficiaries apart from the potential allocation of meat and tracking jobs.

In response to the auction, former president Ian Khama, commented:

“I have been against hunting because it represents a mentality in those who support it to exploit nature for self-interest that has brought about the extinction of many species worldwide. This policy is driven by those who represent an industry that capitalises on ecological destruction. The negative effects are already being felt in the tourism industry, which will threaten our revenues and employment that hunting proponents pretend they want to improve. No scientific work was done on numbers to hunt or places to do so. This new policy will also demotivate those who are engaged in anti-poaching who are being told to save elephants from poachers while the new regime is poaching the same elephants but calling it hunting. How can this government now be trusted to manage controlled hunting despite the rules whilst failing to control poaching?”

Masisi has been lauded by Safari Club International (SCI)’s CEO W Laird Hamberlin, as a “role model for African wildlife conservationists” for reintroducing trophy hunting. He was awarded the “international legislator of the year” award in Reno, Nevada last week at the annual SCI Convention. Clearly, the SCI’s infamous lobbying efforts have paid off.

There is no guarantee that local community members will benefit from these licences distributed to wealthy hunting operators. Community-based natural resource management schemes were a governance mess long before the hunting moratorium was imposed.

There is no good ecological or economic reason to kill any of Botswana’s bull elephants. Hunting will simply create a contest for increased poaching. According to a scientific paper published in Current Biology, over the past two years, an estimated 378 elephants were poached in the country.

Hunting also traumatises elephants and makes them more aggressive towards humans, which will exacerbate human/elephant conflict (HEC). One of the key rationalisations Masisi used to reintroduce hunting was that it would reduce HEC. There is no evidence to support this claim. According to one recent academic paper, most current measures to reduce conflict (such as hunting) “appear to be driven by short-term, site-specific factors that often transfer the problems of human-elephant conflict from one place to another”. Hunting is not a solution; better land-use planning is.

Perhaps of greatest concern regarding Botswana’s 2020 elephant hunting quota is that NG41 – owned by the Mababe Community – has been allocated 20 elephants (the single largest allocation, to be auctioned soon). As is clear from the map, this concession links the Okavango Delta to Chobe National Park and is home to most of the last of Botswana’s great tuskers. Botswana’s Weekend Post reported that ‘a number of concerned businessmen in the tourism sector are chronicling how the former Minister [of Environment, Kitso Mokaila]is lobbying for South Africa’s Johan Calitz of Johan Calitz Safaris to lease a Mababe Concession (NG41).’

Concerning, too, is that in NG49 and CT8, 25 elephants will be hunted along a relatively small area on either side of the Boteti River. The Tuli Block area will see 55 bulls killed in one year. In 2013, four scientists published a paper showing the effects of hunting in that area:

“Hunting of bulls had a direct effect in reducing bull numbers but also an indirect effect due to disturbance that resulted in movement of elephants out of the areas in which hunting occurred. At current rates of hunting, under average ecological conditions, trophy bulls will disappear from the population in less than 10 years. We recommend a revision of the current quotas within each country for the Greater Mapungubwe elephant population, and the establishment of a single multi-jurisdictional (cross-border) management authority regulating the hunting of elephant and other cross-border species.”

The quota allocation is a stark indication that the DWNP has given in to the hunting lobby with no appreciation for the critical importance of older elephant bulls for maintaining elephant institutions and ecological functionality in an open system. It has also ignored the fact that any big-tusked bull is prized by photographers and can be photographed thousands of times during its natural lifetime.

Wisdom suggests that Botswana should abandon short-term rent-seeking in favour of long-term ecological sustainability as the foundation for its economy. Why not allow any willing bidder (such as the EMS Foundation) to pay for these licences if that raises revenue to conserve magnificent bull elephants instead of eliminating them? The fact that conservation organisations are locked out of the bidding shows the hold to which the hunting outfitters and groups like the SCI have on Botswana’s leadership. It’s not about income but in whose pocket it ends up. DM

Hunting auction: Botswana government rides roughshod over conservationists 0

BY ROSS HARVEY - 18TH FEBRUARY 2020 - DAILY MAVERICK

The Botswana government has auctioned off the last of its big tuskers to hunters despite offers from conservationists to buy the licences to save the elephants.

There are probably fewer than 100 big tuskers left in Africa. In its haste to sanction elephant hunts despite offers to save them, the Gaborone government is ignoring both the critical role elephants play in maintaining healthy ecological systems and the future of elephants on the continent. Instead, it’s selling its inheritance for short-term income from an extractive industry.

At a major hunting auction on 7 February, six of the seven packages (of 10 elephants each) were sold to the same white-owned hunting companies that benefited from Botswana’s hunting industry before the 2013 hunting moratorium. One package failed to reach the reserve price.

These 70 licences form the “special elephant quota” of the 2020 hunting quota of 272 elephants. Advertisements for the auctions were only released to the public on 3 February. Interested bidders then had only until 7 February to register – at best an indication of the rushed way in which the reintroduction of hunting to Botswana has been managed; at worst, an indication of pre-decided outcomes.

The EMS Foundation, a South-African based conservation advocacy and research organisation, attempted to bid for the licences. It wrote a letter to Dr Cyril Taolo, the director of Wildlife and National Parks, requesting a revision of the qualifying criteria “to enable us to bid on the hunting packages on the 7th of February 2020 with the express intention that the elephants included in these packages are not hunted should our bids be successful”.

The letter further noted that “we wish to purchase available licences with no intention to hunt elephants, but for the money to be appropriately distributed in a way that benefits conservation”. Local communities would therefore not be deprived of the revenue that would otherwise accrue through auctioning off elephant hunts. Of course, the hunting outfitters would lose out, but communities would have cash in hand, provided appropriate governance mechanisms were established through which to equitably distribute the revenue.

The letter objects to the fact that the bid criteria “explicitly excludes tourism operators or foundations/companies such as ours that do not want to hunt elephants but do desire to fund non-consumptive conservation in Botswana”. Beyond the EMS Foundation, other donors offered funding to buy 10 elephant hunting licences on auction to prevent the animals’ deaths. Clearly, those who are willing to invest directly in conservation activities, and even subsidise revenue shortfalls in areas where non-consumptive tourism is apparently unviable, are overtly excluded from the bidding process.

The licences on auction were 10 each for areas CT4, CT7, CT29, NG8, NG9, NG11 and NG35. Ngamiland concessions 8, 9 and 11 are held by local communities.

Local communities in NG3 objected to hunting in their concession (where a hunting disaster occurred in 2019 involving the shooting of a collared research bull). Consequently, there is no 2020 quota for NG3, but the quotas for some of the neighbouring concessions appear too high.

There has also been no consideration given to maintaining hunting-free corridors in critical areas such as NG41, which will be auctioned later. This suggests that the quota is not based on science; the way in which it has been divided up is arbitrary. Moreover, a confidential letter from a community in NG8 has expressed to the government that it does not want hunting, which it sees as undermining its projects to raise support for building self-sustaining tourism initiatives. If there is science to support the quota and the way in which it has been allocated, this should be made publicly available. Until such time as this is provided, it would appear responsible for the international community to ban trophy imports from Botswana.

The results of the auction are telling. Six 10-elephant packages sold for between $330,000 and $435,000 each. The package for CT29 did not sell because it did not fetch the minimum clearing price. The government amassed a total of $2,355,000 for six packages. There is no indication of how this money will be spent.

Successful bidders will now look to sell elephant hunts for upwards of $60,000 per elephant, normally paid into foreign bank accounts. At an average cost of $39,250, the margins are impressive. But who will benefit? Hunters would have us believe that local communities are the primary beneficiaries. However, one study showed that only 3% of hunting revenue eventually trickles down to them; at best hunting only contributes an average of 1.8% of African tourism revenue.

CT4 and NG9 both went to Jeff Rann Safaris, which is now offering a 10-day elephant hunt for $85,000 on its website. A joint shareholder is Professor Joseph Mbaiwa of the Okavango Research Institute who has long been an advocate of lifting the Khama-era moratorium on hunting in Botswana. Mbaiwa became a shareholder (in November 2019), shortly after President Mokgweetsi Masisi decided to bring hunting back to Botswana last year. CT7 went to Leon Kachelhoffer, NG8 went to Clive Eaton (along with NG11, in partnership with Kaz Kader). NG35 went to Grant Albers (apparently for Kerry Krottinger, a Texas oilman with a long history of big game hunting in Africa). There are no obvious local community beneficiaries apart from the potential allocation of meat and tracking jobs.

In response to the auction, former president Ian Khama, commented:

“I have been against hunting because it represents a mentality in those who support it to exploit nature for self-interest that has brought about the extinction of many species worldwide. This policy is driven by those who represent an industry that capitalises on ecological destruction. The negative effects are already being felt in the tourism industry, which will threaten our revenues and employment that hunting proponents pretend they want to improve. No scientific work was done on numbers to hunt or places to do so. This new policy will also demotivate those who are engaged in anti-poaching who are being told to save elephants from poachers while the new regime is poaching the same elephants but calling it hunting. How can this government now be trusted to manage controlled hunting despite the rules whilst failing to control poaching?”

Masisi has been lauded by Safari Club International (SCI)’s CEO W Laird Hamberlin, as a “role model for African wildlife conservationists” for reintroducing trophy hunting. He was awarded the “international legislator of the year” award in Reno, Nevada last week at the annual SCI Convention. Clearly, the SCI’s infamous lobbying efforts have paid off.

There is no guarantee that local community members will benefit from these licences distributed to wealthy hunting operators. Community-based natural resource management schemes were a governance mess long before the hunting moratorium was imposed.

There is no good ecological or economic reason to kill any of Botswana’s bull elephants. Hunting will simply create a contest for increased poaching. According to a scientific paper published in Current Biology, over the past two years, an estimated 378 elephants were poached in the country.

Hunting also traumatises elephants and makes them more aggressive towards humans, which will exacerbate human/elephant conflict (HEC). One of the key rationalisations Masisi used to reintroduce hunting was that it would reduce HEC. There is no evidence to support this claim. According to one recent academic paper, most current measures to reduce conflict (such as hunting) “appear to be driven by short-term, site-specific factors that often transfer the problems of human-elephant conflict from one place to another”. Hunting is not a solution; better land-use planning is.

Perhaps of greatest concern regarding Botswana’s 2020 elephant hunting quota is that NG41 – owned by the Mababe Community – has been allocated 20 elephants (the single largest allocation, to be auctioned soon). As is clear from the map, this concession links the Okavango Delta to Chobe National Park and is home to most of the last of Botswana’s great tuskers. Botswana’s Weekend Post reported that ‘a number of concerned businessmen in the tourism sector are chronicling how the former Minister [of Environment, Kitso Mokaila]is lobbying for South Africa’s Johan Calitz of Johan Calitz Safaris to lease a Mababe Concession (NG41).’

Concerning, too, is that in NG49 and CT8, 25 elephants will be hunted along a relatively small area on either side of the Boteti River. The Tuli Block area will see 55 bulls killed in one year. In 2013, four scientists published a paper showing the effects of hunting in that area:

“Hunting of bulls had a direct effect in reducing bull numbers but also an indirect effect due to disturbance that resulted in movement of elephants out of the areas in which hunting occurred. At current rates of hunting, under average ecological conditions, trophy bulls will disappear from the population in less than 10 years. We recommend a revision of the current quotas within each country for the Greater Mapungubwe elephant population, and the establishment of a single multi-jurisdictional (cross-border) management authority regulating the hunting of elephant and other cross-border species.”

The quota allocation is a stark indication that the DWNP has given in to the hunting lobby with no appreciation for the critical importance of older elephant bulls for maintaining elephant institutions and ecological functionality in an open system. It has also ignored the fact that any big-tusked bull is prized by photographers and can be photographed thousands of times during its natural lifetime.

Wisdom suggests that Botswana should abandon short-term rent-seeking in favour of long-term ecological sustainability as the foundation for its economy. Why not allow any willing bidder (such as the EMS Foundation) to pay for these licences if that raises revenue to conserve magnificent bull elephants instead of eliminating them? The fact that conservation organisations are locked out of the bidding shows the hold to which the hunting outfitters and groups like the SCI have on Botswana’s leadership. It’s not about income but in whose pocket it ends up. DM

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67388

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Hunting in Botswana

Botswana government won’t let the truth get in the way of its trophy hunting narrative

BY ROSS HARVEY - 5TH MARCH 2020 - BOTSWANA GUARDIAN

Symptomatic of the Botswana government’s shaky relationship with reality is its letter to the United Kingdom’s Department of Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA). A full week after the deadline (25 February 2020) for public submissions on whether the UK should ban trophy imports, Philda Kereng, Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation and Tourism, wrote to DEFRA expressing her “discomfort” on how the UK is handling the matter. The process was initiated on 2 November 2019 and involved a considered “call for evidence on the scale and impacts of the import and export of hunting trophies.”

Kereng rightly states that “DEFRA’s position on this matter should be based on the best available scientific evidence and information.” Refreshingly, her government “stands ready to provide DEFRA with significant and accurate evidence” that demonstrates “the importance of hunting as a conservation strategy.” Such evidence is as yet not publicly available or forthcoming, however, and stands in stark contrast to the growing global evidence that shows trophy hunting to be a short-term strategy with significant long-term costs. Consider, for instance, that:

“…the livelihoods benefits from wildlife hunting safaris were never sustainable in the long term. The wildlife hunting practice under the then joint venture partnership (JVP) model had created dependency among local communities who were subsisted by providing cheap labour in professional hunting companies” (Blackie, 2018).

Clearly, the hunting moratorium, imposed in early 2014, resulted in some livelihood benefit losses. But the ‘benefits’ from hunting are, nonetheless, not sustainable in the long run. Second, while Blackie argues for hunting ‘problem animals’ such as elephant and buffalo to increase frustration tolerance for human and wildlife conflict (a very shaky argument, in my view), it speaks directly to the Botswana government’s “commitment to manage and conserve its wildlife and provide livelihood support benefits to impoverished communities.” Minister Kereng insists that “communities were stripped of livelihood benefits including cash, infrastructure and game meat following the hunting moratorium.” But throwing a bit of elephant meat and some tracking or skinning jobs to local communities is not sustainable; it’s insulting. No plan exists to show how community trusts will be reconstituted to ensure an equitable distribution of hunting revenue to community members.

Mucha Mkono notes that trophy hunting perpetuates a colonial extraction mentality, which we had hoped Botswana would have emancipated itself from. Attempting to justify a morally problematic activity on the grounds that it produces economic benefits ignores the question of who is carrying out the activity and who might benefit disproportionately. As Mike Cadman explains: “the hunting packages were bought by a few wealthy and well-connected individuals who had run hunting operations in Botswana prior to the moratorium.” Trophy hunting is also likely to have unintended consequences such as increased aggression due to the elimination of older bulls, which are in turn the very bulls that photographers pay top dollar to shoot.

Minister Kereng states that the government decided to reintroduce the practice after a “nationwide, democratic and (sic) consultation with the affected stakeholders”, but the findings have still not been written up in any scientifically robust way. For instance, it is not clear what methodology was employed, how the sample was stratified to ensure representativity, or how the data was then verified for accuracy. We know, however, that the consultation occurred during the peak of the tourism season in 2019 (ahead of elections) when many community members were not available to be consulted. Interestingly, communities in Ngamiland voted overwhelmingly for the opposition Umbrella for Democratic Change, which opposes hunting. But let us grant the minister that a consensus nonetheless existed; the fact remains that trophy hunting is not a long-term solution to Botswana’s conservation and tourism interests.

Beyond this, the minister’s assertions bear little resemblance to the truth.

First, the idea that Botswana’s elephant population of 130,000 exceeds the country’s “carrying capacity of 50,000” has no scientific basis. The concept has no relevance in an open, dynamic ecological system such as Botswana’s. Uneven, regenerative landscape impact through elephant seed dispersal and ecosystem engineering should be ecologically encouraged. But the government nonetheless repeats ad nauseum that “the number [of elephants]and high levels of human-elephant conflict [HEC] and the consequent impact on livelihoods was increasing.” But Botswana’s own Department of Wildlife and National Parks has estimated elephant numbers at around 130,000 since 2001, and HEC was prevalent long before the 2013 moratorium.

Second, Minister Kereng contends that “controlled hunting is “a tolerance building mechanism for communities in marginal lands living amongst destructive wildlife such as elephants.” This demonstrates a severe lack of understanding of the causal factors driving HEC. At the root of the problem is water scarcity, exacerbated by climate change. A growing human population is competing with elephants for scarce resources. To argue that a bit of elephant meat and some colonial jobs will compensate for crop-raiding and the occasional death of loved ones is naïve in the extreme, given that elephants tend to respond to trauma induced by the loss of herd members (through trophy hunting or poaching) by becoming more aggressive towards people. This negatively affects communities living with elephants as well as the wildlife watching tourism industry.

Finally, Botswana has purportedly “developed a scientific and sustainable hunting framework… based on the best available scientific evidence”. This is laughable, along with the idea that controlled hunting will somehow “enhance the survival of hunted species in the wild”. Shooting bull elephants (who are increasingly reproductively fit over a natural lifespan) undermines herd functionality and long-run survival probability. Shooting prime male lions similarly induces infanticide, hardly enhancing species survival likelihood (yes, prime males get shot instead of ‘surplus’ males because hunters select the best not the weakest). Setting a quota for 2020 for 272 bull elephants to be shot has no basis in science. The random allocation across concessions is less an exercise in science (it does not account for density or dispersal) than in extracting rents. A scientific framework would provide evidence, for instance, that shooting older elephant bulls in NG2,4,5 and 8 will not negatively impact that unique elephant population, or that shooting bulls in NG41 will not wipe out the last of the big tuskers, or that resuming hunting in the Tuli Block will not ignore the science produced just before the ban which showed hunting to be unsustainable in that area. Plucking numbers from thin air is not science, it’s gambling.

Beyond science, serious governance questions arise: No concession holder exists for CT2 – a large hunting area southeast of Chobe national park – and yet an elephant hunting package for 10 elephants will be auctioned off later this year for that very concession. Professor Mbaiwa, who long advocated a return to hunting, is now a shareholder with hunter Jeffrey Rann in a new joint venture. Corruption evidently abounded before the moratorium and looks set to take off again.

The Botswana government is gambling its heritage away and hoping like hell that some of the resultant meat and skinning jobs will keep poor, rural Batswana satisfied. Dressing this up as ‘science’ and telling DEFRA that it’s “incomprehensible that the UK would seek to undermine our conservation strategy” looks more like a line out of the hunting propaganda handbook than conservation policy.

[1] Independent economist and wildlife policy analyst consulting to the EMS Foundation and The Conservation Action Trust in South Africa.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67388

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Hunting in Botswana

Elephant Hunts for Sale During a Pandemic

BY ROSS HARVEY - 13TH APRIL 2020 - THE RELEVATOR

Botswana hides behind national “sovereignty” while selling off its natural heritage to foreign hunters and treating elephants as mere commodities.

In February 2020 the government of Botswana auctioned off the right to hunt and kill 60 elephants — the first salvo toward a quota that aimed to allow the trophy hunting of 272 elephants this year.

Plans for those hunts, which would have been the first since the country’s 2013 hunting moratorium, were put on hold in late March by the worldwide pandemic when Botswana banned travelers from the United States and other “high-risk” countries. But the Botswana Wildlife Producers Association, which represents the hunting industry, quickly asked for an extension of this year’s hunting season.

If the COVID-19 lockdowns end sometime soon, the bullets could quickly begin flying.

Botswana is a cash-strapped nation, so one can perhaps understand the short-term attraction of trophy hunting. The government made $2.3 million in a few hours on that February afternoon from selling 60 elephants at an average of $39,000 per head.

The pandemic has not slowed this thirst for short-term profits. On 27 March, just a few days after Botswana closed its borders, it reportedly auctioned off additional hunting rights for 15 elephants, two leopards and dozens of other animals for a total of $540,000. The auction results have not been publicly reported, but were conveyed to me by a present, concerned party.

An Elephant’s Value

To ecological economists like me, the push for trophy hunts seems to severely undervalue these magnificent creatures.

Notwithstanding their obvious intrinsic value, elephants most likely have even greater ecological-economic value than these hunting permits reflect.

For one thing, each elephant contributes to the dynamics of the ecosystem and improves the functionality of forests and savannahs as effective carbon sinks. A whole host of other species depend on elephants’ movements, which create forest corridors and shape the habitat. Elephant droppings fertilize forests and savannas and carry seeds to new locations. Even tiny tadpoles have been known to live in elephant footsteps.

Elephant in Botswana’s Okavango Delta. Photo © Ross Harvey, used with permission.

And then there’s the value to people. A 2014 report estimated that elephants are each worth more than $1.6 million in ecotourism alone. Purchasing an elephant at an auction for $39,000 and selling it on to a trophy hunter for $85,000, therefore, seems not only ethically callous but economically senseless.

Elephants are not alone in this. Recent work by International Monetary Fund economists estimated the value of a single whale at $2 million over its lifetime due to its roles in carbon sequestration, the growth of carbon-absorbing and oxygen-generating phytoplankton, and whale-watching tourism. They estimate that the world’s population of whales alone are worth a staggering $1 trillion. Obviously, there are no whales in Botswana, but the research illustrates the growing trend of valuing large megafauna well beyond their charismatic appearances.

An Important History

The Botswana government, under former president Ian Khama, originally placed a moratorium on trophy hunting back in 2013. In May 2019 the current government justified hunting’s reintroduction as an element of the country’s “sovereign right” — while at the same time abrogating this right to a foreign hunting organization, Safari Club International, which now openly boasts of how it influenced the decision.

During the moratorium wildlife and tourism groups lauded Botswana as a haven for elephants, a conservation and marketing success that saw rapid growth in the country’s ecotourism industry.

When President Mokgweetsi Masisi came to power, however, the political narrative changed from recognizing elephants as critical to the country’s success to labelling them as a problem to be “managed.” The president and other cabinet members have repeatedly peddled the view that there are “too many” elephants and that they are responsible for environmental damage and increased human-elephant conflict.

Of course, this myth has been repeatedly exposed and debunked.

That debunking hasn’t changed Botswana’s messaging. Trophy hunting, the world is told, will result in benefits such as meat, revenue and jobs for local communities in rural areas close to wildlife. These benefits will purportedly increase “frustration tolerance” (acceptance of the risk of living near elephants) among local community members, thus indirectly serving conservation ends.

Excluded from this new narrative is an acknowledgment that the moratorium was originally imposed because of the widespread failures of governance in community trusts. Abuses in the hunting industry were rife. There was also no evidence that trophy hunting revenues were equitably distributed or that hunting was contributing to wildlife conservation. In fact, wildlife numbers for many species were in decline by 2012, and excessive trophy hunting was considered among the potential causes of the decline. There’s good evidence to substantiate this, so the government cannot now argue that the ban was “not scientifically based.”

Moreover, the growth in Botswana’s tourism industry in the wake of the moratorium was remarkable, with increases in both the number of tourists and profits — not to mention growing elephant populations. This alone supports the idea of keeping photographic tourism as the primary revenue opportunity for elephants and other wildlife.

It’s not without criticism, however. We must also recognize that the Botswana Tourism Organisation — set up by the government to take a 65% share of photographic-community joint-venture revenue (leaving only 35% for communities that live with or near wildlife) — has been a governance disaster. In addition, the barriers for citizens to enter the tourism industry are impossibly high. They face formidable red tape in the licensing process and must conduct their own environmental impact assessments, which cost time and a lot of money.

These are long-term problems to solve, regardless of what type of tourism we’re talking about.

Trophy Hunting Is Not Conservation

But the growth of photographic tourism and wildlife populations are not discussed by the current government. Instead the narrative persists that trophy hunting will indirectly serve conservation by giving communities the tools and resources to withstand any human-elephant conflict they encounter. No clear evidence exists, however, that this type of conflict has increased since the moratorium, and it was prevalent long before then.

In fact research shows that hunting makes human-elephant conflict worse. The violent deaths of elder elephants creates intergenerational trauma, leading to increased aggression and delinquent behavior among young bulls. Growing human populations and resultant competition over access to water, which will become increasingly scarce under climate change, will make things even worse.

Elephants in Botswana’s Okavango Delta. Photo © Ross Harvey, used with permission.

Trophy hunting is therefore a short-term non-solution to human-elephant conflict.

Yes, some communities lost short-term hunting revenue after the moratorium was put in place, but that should not serve as cause to invite hunting’s return — not even for communities now facing the spectre of lost tourism income during the pandemic.

A Tragedy in the Making

Lifting the hunting moratorium under the guise of a country’s “sovereign right” is Orwellian doublespeak. Botswana does not own Africa’s shared elephants, which migrate between countries, yet the government has sold them out to foreign hunters and to satisfy foreign interests like Safari Club International. The long-term opportunity costs of hunting have not been considered, yet the government blindly insists that it will produce “significant conservation benefits.” Two plus two equals five here. There is no evidence that the Ministry’s decision has been guided by “the highest ethical standards and principles of science-based sustainability.” No publicly available science warrants the quota of 272 elephants for 2020, let alone the arbitrary allocation across sensitive areas and other areas which likely cannot sustain hunting at all.

Botswana’s decision to lift the trophy-hunting moratorium was ill advised at best and an indication of short-term rent-seeking at worst. It’s ecologically unsustainable, undermining the very foundations of the country’s recent ecotourism successes. Attempting to justify it under the banner of “sovereignty” raises questions, as the right to kill public heritage is being granted to wealthy foreign hunters. The ultimate tragedy is that the rural poor living with or near wildlife will be no better off.

And Botswana’s selling additional hunting rights during a worldwide pandemic, when the world’s attention is elsewhere, shows that the government does not care about its people or its elephants — only short-term profits.

COVID-19 has exposed humanity’s propensity to treat wild animals as mere commodities to be consumed. Animals slaughtered at wet meat markets in Wuhan were the most likely intermediary source of zoonotic spillover — possibly involving transmission of a bat virus from animals to humans. Trophy hunting reflects the very same mentality, that wild animals exist only for our entertainment and consumption.

It would be a real tragedy if these planned hunts simply resumed when the current lockdowns are lifted.

Original article: https://therevelator.org/elephant-hunts-pandemic/

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Peter Betts

- Posts: 3084

- Joined: Fri Jun 01, 2012 9:28 am

- Country: RSA

- Contact:

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67388

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Hunting in Botswana

Elephant hunting – Botswana grants 287 licenses

Posted on April 2, 2021 By Melissa Reitz - Supplied by Political Animal Lobby

Botswana has granted permission for 287 elephants to be hunted as it gears up for its first trophy elephant hunting season since the ban was controversially lifted two years ago.

With Covid-19 restrictions disrupting last year’s hunting season, 187 existing elephant licences have been tagged onto this year’s 100 licences. The licences were auctioned for up to US$43,000 each.

A variety of other species are also allowed to be shot between April and September, including leopard.

In the face of a global outcry, president Mokgweetsi Masisi reopened trophy hunting in 2019 after former Botswanan president, Ian Khama, banned it in 2014 to conserve the country’s wildlife. Masisi’s government cites that the sport provides a solution to growing human-elephant conflict and provides income for local communities.

“Human-driven habitat loss is fast becoming the ‘silent killer’, almost as big a threat as poaching is to elephants,” says Adrienne West of Political Animal Lobby (PAL). “We are losing Africa’s elephants at a rapid rate, and it is outrageous that one of their most important range states would choose to put their lives up for sale.”

Conservationists and ecological experts dispute hunting as an effective measure against human-wildlife conflict.

“Shooting these elephants will do nothing to reduce the incidence of crop-raiding in farming areas, as most of the killing would take place in trophy hunting blocks that are some distance away,” says Dr Keith Lindsay of the Amboseli Trust for Elephants.

“In fact, shooting elephants could increase tensions between farmers and elephants – they can communicate over many kilometres, and when elephants are killed in one area, the alarm and disturbance would be felt some distance away.”

Elephants are a keystone species, and scientists say there is no ecological reason to reduce their numbers by killing them as they play an important role in ecosystem health and diversity.

Over the past decade, Africa has lost more than 30% of its elephants to ongoing ivory poaching, which is having devasting effects on populations across the continent.

Figures on the CITES international trade database reveal that Botswana’s trophy hunting ban of seven years saved more than 2,000 elephants and 140 leopards from being shot.

Botswana holds the world’s largest population of approximately 130 000 elephants, which share transboundary migrations routes with neighbouring countries, including Namibia and Zimbabwe. During the hunting ban, reports of increased numbers in Botswana suggested that migrating elephants sought refuge in the safety of the then hunt-free country.

Posted on April 2, 2021 By Melissa Reitz - Supplied by Political Animal Lobby

Botswana has granted permission for 287 elephants to be hunted as it gears up for its first trophy elephant hunting season since the ban was controversially lifted two years ago.

With Covid-19 restrictions disrupting last year’s hunting season, 187 existing elephant licences have been tagged onto this year’s 100 licences. The licences were auctioned for up to US$43,000 each.

A variety of other species are also allowed to be shot between April and September, including leopard.

In the face of a global outcry, president Mokgweetsi Masisi reopened trophy hunting in 2019 after former Botswanan president, Ian Khama, banned it in 2014 to conserve the country’s wildlife. Masisi’s government cites that the sport provides a solution to growing human-elephant conflict and provides income for local communities.

“Human-driven habitat loss is fast becoming the ‘silent killer’, almost as big a threat as poaching is to elephants,” says Adrienne West of Political Animal Lobby (PAL). “We are losing Africa’s elephants at a rapid rate, and it is outrageous that one of their most important range states would choose to put their lives up for sale.”

Conservationists and ecological experts dispute hunting as an effective measure against human-wildlife conflict.

“Shooting these elephants will do nothing to reduce the incidence of crop-raiding in farming areas, as most of the killing would take place in trophy hunting blocks that are some distance away,” says Dr Keith Lindsay of the Amboseli Trust for Elephants.

“In fact, shooting elephants could increase tensions between farmers and elephants – they can communicate over many kilometres, and when elephants are killed in one area, the alarm and disturbance would be felt some distance away.”

Elephants are a keystone species, and scientists say there is no ecological reason to reduce their numbers by killing them as they play an important role in ecosystem health and diversity.

Over the past decade, Africa has lost more than 30% of its elephants to ongoing ivory poaching, which is having devasting effects on populations across the continent.

Figures on the CITES international trade database reveal that Botswana’s trophy hunting ban of seven years saved more than 2,000 elephants and 140 leopards from being shot.

Botswana holds the world’s largest population of approximately 130 000 elephants, which share transboundary migrations routes with neighbouring countries, including Namibia and Zimbabwe. During the hunting ban, reports of increased numbers in Botswana suggested that migrating elephants sought refuge in the safety of the then hunt-free country.

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

- Lisbeth

- Site Admin

- Posts: 67388

- Joined: Sat May 19, 2012 12:31 pm

- Country: Switzerland

- Location: Lugano

- Contact:

Re: Hunting in Botswana

Botswana Government to shoot 287 elephants by the end of September

BY BORIS NGOUNOU - 12TH APRIL 2021 - AFRIK21

The elephant hunting season opened on April 6th, 2021 in Botswana. The Botswana authorities have issued permits to kill 287 pachyderms by the end of the season in September 2021. But this operation is not to the liking of environmentalists, who see it as the destruction of biodiversity. In March 2021, African elephants were declared endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

In Botswana, Map Ives is one of the conservationists opposing the 2021 elephant hunting season, which was launched on April 6th, 2021 in Gaborone in the southeast of the country. I understand that hunting can be useful as a [wildlife]management tool,” says Map Ives, “but it should be based on science, and unfortunately in Botswana we don’t have the financial resources or the trained manpower to do population research on different species,” says the national coordinator of Rhino Conservation Botswana. Map Ives’ concerns are consistent with the latest statistics from the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) on African elephants.

In its new red list of endangered animals, the IUCN classifies the savanna elephant (Loxodonta Africana) as “endangered” and its cousin, the forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) as “critically endangered”. According to the organisation, the African elephant population has fallen by 86% in 30 years. The main causes are the destruction of their habitat and hunting.

Responsible and ethical hunting?

Botswana has the largest elephant population in the world, estimated at around 130 000. In 2019, the country lifted a total ban on hunting, introduced five years earlier to reverse the decline in elephant and other species. The lifting of the ban was adopted by the current President of the Republic, Mokgweetsi Masisi, who believes that the uncontrolled growth of the pachyderm population is threatening the livelihoods, including crops, of local people.

For this year, Botswana authorities have issued about 100 hunting permits, with an additional 187 permits from the last season suspended due to restrictions related to the Coronavirus pandemic.

The Botswana Wildlife and National Parks Authority has given assurances of responsible and ethical hunting. Applicants for the hunt should have ‘proven experience of elephant hunting’ and no criminal convictions for wildlife offences. In addition, the hunting of collared elephants is prohibited and all expeditions must be accompanied at all times by a tour guide and a professional hunter.

Original article: https://www.afrik21.africa/en/botswana- ... september/

"Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world." Nelson Mandela

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge

The desire for equality must never exceed the demands of knowledge